Twelve Medieval Ghost Stories

English Translation

Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, Vol 27, 1924

The following ghost stories were published by Dr. M. R. James, the Provost of Eton College, in the English Historical Review of July 1922, in a careful transcript from the original Latin. Their connection with Byland Abbey, the appearance in them of well-known Yorkshire villages and names, recommended them for republication in the Yorks. Arch. Journal. They have been translated into English to make them accessible to a wider public than could be expected to penetrate the medieval Latin. Dr. James’ introduction is reprinted, and also his notes except in so far as they refer to difficulties in the Latin. Other notes have been added by Dr. Hamilton Thompson, who has also given me much assistance and saved me from mistakes in translating the Latin. Dr. Thompson has also added a topographical note which he has compiled with the assistance of Dr. William Brown.

The thanks of the Yorkshire Archaeological Society are due to Dr. James and to Mr. G. N. Clark, M.A., the Editor of the English Historical Review, for permission to translate and print these stories.

A. J. Grant.

Twelve Medieval Ghost Stories #

These stories were, I believe, first noticed in the recent Catalogue of the Royal Manuscripts, where a brief analysis of them is given which may well have excited the curiosity of others beside myself. All that Casley has to say of them in the old catalogue is “Exemplaria apparitionum spirituum (saec.) XV.”

I took an early opportunity of transcribing them, and I did not find them disappointing; I hope others will agree that they deserve to be published.

The source is the Royal MS. 15, A. XX, in the British Museum. It is a fine volume of the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, containing some tracts of Cicero and the Elucidarium. It belonged to Byland Abbey (Yorkshire) and later to John Theyer.

On blank pages in the body of the book (ff. 140-3) and at the end (fo. 163 h) a monk of Byland has written down a series of ghost stories, of which the scenes are laid in his own neighbourhood. They are strong in local colour, and, though occasionally confused, incoherent and unduly compressed, evidently represent the words of the narrators with some approach to fidelity.

To me they are redolent of Denmark. Anyone who is lucky enough to possess E. T. Christensen’s delightful collections of Sagn fra Jylland will be reminded again and again of traits which occur there. Little as I can claim the quality of “folklorist,” I am fairly confident that the Scandinavian element is really prominent in these tales.

The date of the writing cannot be long after 1400 (c. 1400 is the estimate of the catalogue). Richard II’s reign is referred to as past. A study of local records, impossible to me, might not improbably throw light upon the persons mentioned in the stories.

The hand is not a very easy one, and the last page of all is really difficult; some words have baffled me. The Latin is very refreshing.

M. R. James.

I. Concerning the ghost of a certain labourer at Ryevaulx who helped a man to carry beans. #

A certain man was riding on his horse carrying on its back a peck of beans. The horse stumbled on the road and broke its shin bone; which when the man saw he took the beans on his own back. And while he was walking on the road he saw as it were a horse standing on its hind feet and holding up its fore feet. In alarm he forbade the horse in the name of Jesus Christ to do him any harm. Upon this it went with him in the shape of a horse, and in a little while appeared to him in the likeness of a revolving haycock1 with a light in the middle; to which the man said, “God forbid that you bring evil upon me.” At these words it appeared in the shape of a man and the traveller conjured him. Then the spirit told him his name and the reason (of his walking) and the remedy, and he added, “Permit me to carry your beans and to help you.” And thus he did as far as the beck but he was not willing to pass over it ; and the living man knew not how the bag of beans was placed again on his own back. And afterwards he caused the ghost to be absolved and masses to be sung for him and he was eased.

II. Concerning a wonderful encounter between a ghost and a living man in the time of King Richard II. #

It is said that a certain tailor of the name of [blank] Snowball was returning on horseback one night from Gilling to his home in Ampleforth, and on the way he heard as it were the sound of ducks washing themselves in the beck, and soon after he saw as it were a raven that flew round his face and came down to the earth and struck the ground with its wings as though it were on the point of death. And the tailor got off his horse to take the raven, and as he did so he saw sparks of fire shooting from the sides of the raven. Whereupon he crossed himself and forbade him in the name of God to bring at that time any harm upon him. Then it flew off with a great screaming for about the space of a stone’s throw. Then again he mounted his horse and very soon the same raven met him as it flew, and struck him on the side and threw the tailor to the ground from the horse upon which he was riding ; and he lay stretched upon the ground as it were in a swoon and lifeless, and he was very frightened.

Then, rising and strong in the faith, he fought with him with his sword until he was weary; and it seemed to him that he was striking a peat-stack; and he forbade him and conjured him in the name of God, saying, “God forbid that you have power to hurt me on this occasion, but begone.”

And again it flew off with a horrible screaming as it were the space of the flight of an arrow. And the third time it appeared to the tailor as he was carrying the cross of his sword upon his breast for fear, and it met him in the likeness of a dog with a chain on its neck. And when he saw it the tailor, strong in the faith, thought within himself, "What will become of me? I will adjure him in the name of the Trinity and by the virtue of the blood of Christ from His five wounds that he speak with me, and do me no wrong, but stand fast and answer my questions and tell me his name and the cause of his punishment and the remedy that belongs to it.” And he did so.

And the spirit, panting terribly and groaning, said, “Thus and thus did I, and for thus doing I have been excommunicated.2 Go therefore to a certain priest and ask him to absolve me. And it behoves me to have the full number of nine times twenty masses celebrated for me.

And now of two things you must choose one. Hither you shall come back to me on a certain night alone bringing to me the answer of those whose names I have given you; and I will tell you how you may be made whole, and in the mean time you need not fear the sight of a wood fire.3 Or otherwise your flesh shall rot and your skin shall dry up and shall fall off from you utterly in a short time.

Know moreover that I have met you now because to-day you have not heard mass nor the gospel of John (namely in principio), and have not seen the consecration of our Lord’s body and blood, for otherwise I should not have had full power of appearing to you."4

And as he spoke with the tailor he was as it were on fire and his inner parts could be seen through his mouth and he formed his words in his entrails and did not speak with his tongue. Then the tailor asked permission from the ghost that he might have with him on his return some companion.

But the ghost said, “No; but have upon you the four gospels and the name of victory, namely Jesus of Nazareth, on account of two other ghosts that abide here of whom one cannot speak when he is conjured and abides in the likeness of fire or of a bush and the other is in the form of a hunter and they are very dangerous to meet. Pledge me further on this stone that you will defame my bones5 to no one except to the priests who celebrate on my behalf, and the others to whom you are sent on my behalf, who may be of use to me.”

And he gave his word upon the stone that he would not reveal the secret, as has been already explained. Then he conjured the ghost to go to Hodgebeck6 and to await his return. And the ghost said, “No, no," and screamed.

And the tailor said, Go then to Byland Bank, whereat he was glad.

The man of whom we speak was ill for some days, but then got well and went to York to the priest who had been mentioned, who had excommunicated the dead man, and asked him for absolution. But he refused to absolve him, and called to him another chaplain to take counsel with him. And that chaplain called in another, and that other a third, to advise secretly concerning the absolution of this man .7

And the tailor asked of him, “Sir, you know the mutual token that I hinted in your ear.” And he answered, Yes, my son.”

Then after many negotiations the tailor made satisfaction and paid live shillings and received the absolution written on a piece of parchment, and he was sworn not to defame the dead man but to bury the absolution in his grave near his head, and secretly. And when he had got it he went to a certain brother Richard of Pickering, a confessor of repute, and asked him whether the absolution were sufficient and lawful. And he answered that it was. Then the tailor went to all the orders of the friars of York and he had almost all the required masses celebrated during two or three days, and coming home he buried the absolution in the grave as he had been ordered.

And when all these things had been duly carried out he came home, and a certain officious neighbour of his, hearing that he had to report to the ghost on a certain night all that he had done at York, adjured him, saying, “God forbid that you go to this ghost without telling me of your going and of the day and the hour.”

And being so constrained, for fear of displeasing God, he told him, waking him up from sleep and saying, “I am going now. If you wish to come with me let us set off and I will give you a part of the writings that I carry on me because of night fears.”

Then the other said, “Do you want me to go with you,” and the tailor said, You must see to that; I will give no advice to you.” Then at last the other said, “Get you gone in the name of the Lord and may God prosper you in all things.”8

After these words he came to the appointed place and made a great circle with a cross910 and he had upon him the four gospels and other holy words and he stood in the middle of the circle and he placed four reliquaries in the form of a cross on the edge of the circle; and on the reliquaries were written words of salvation, namely Jesus of Nazareth, etc., and he waited for the coming of the ghost. He came at length in the form of a she-goat and went thrice round the circle saying, “Ah! ah! ah! ” And when he conjured the she-goat she fell prone upon the ground, and rose up again in the likeness of a man of great stature, horrible and thin, and like one of the dead kings in pictures.1112

And when he was asked whether the tailor’s labour had been of service to him, he answered, “Yes, praised be God. And I stood at your back when you buried my absolution in my grave at the ninth hour and were afraid. No wonder you were afraid, for three devils were present there who have tormented me in every way from the time when you first conjured me to the time of my absolution, suspecting that they would have me but very little time in their custody to torment me. Know therefore that on Monday next I shall pass into everlasting joy with thirty other spirits. Go now to a certain beck and you will find a broad stone; lift it up and under it you will find a sand stone. Wash your whole body with water and rub it with the stone and you will be whole in a few days."13

When he was asked the names of the two ghosts, he answered, “I cannot tell you their names.” And when asked about their condition he answered that "one was a layman and a soldier and was not of these parts, and he killed a woman great with child and he will find no remedy before the day of judgment, and you will see him in the form of a bullock without mouth or eyes or ears; and however you conjure him he will not be able to speak. And the other was a man of religion in the shape of a hunter blowing upon a horn; and he will find a remedy and he will be conjured by a certain boy who has not yet come to manhood, if the Lord will.”

And then the tailor asked the ghost of his own condition and received answer, "You are keeping wrongfully the cap and coat of one who was your friend and companion in the wars beyond the seas. Give satisfaction to him or you will pay dearly for it.”

And the tailor said, " I know not where he lives ”; and the ghost answered, " He lives in such a town near to the castle of Alnwick.”

When further he was asked, "What is my greatest fault ?” the ghost answered, " Your greatest fault is because of me.” And the man said, How and in what way ? ” And the ghost answered, " Because the people sin telling lies concerning you and bringing scandal on other dead men saying the dead man who was conjured was he or he— or he.”

And he asked the ghost, "What shall I do? I will reveal your name?” And he said, "No; but if you stay in one place you will be rich, and in another place you will be poor, and you have here certain enemies .”14

Then the spirit said, " I can stay no longer talking with you.” And as they went their different ways, the deaf and dumb and blind bullock went with the man as far as the town of Ampleforth; whom he conjured in all the ways that he knew, but by no means could he make answer. And the ghost that had been aided by him advised him to keep all his best writings by his head until he went to sleep. " And say neither more nor less than I advise you and keep your eyes on the ground and look not on a wood fire for this night at least .”15 And when he came home he was seriously ill for several days.16

Notes on “the great circle with a cross” #

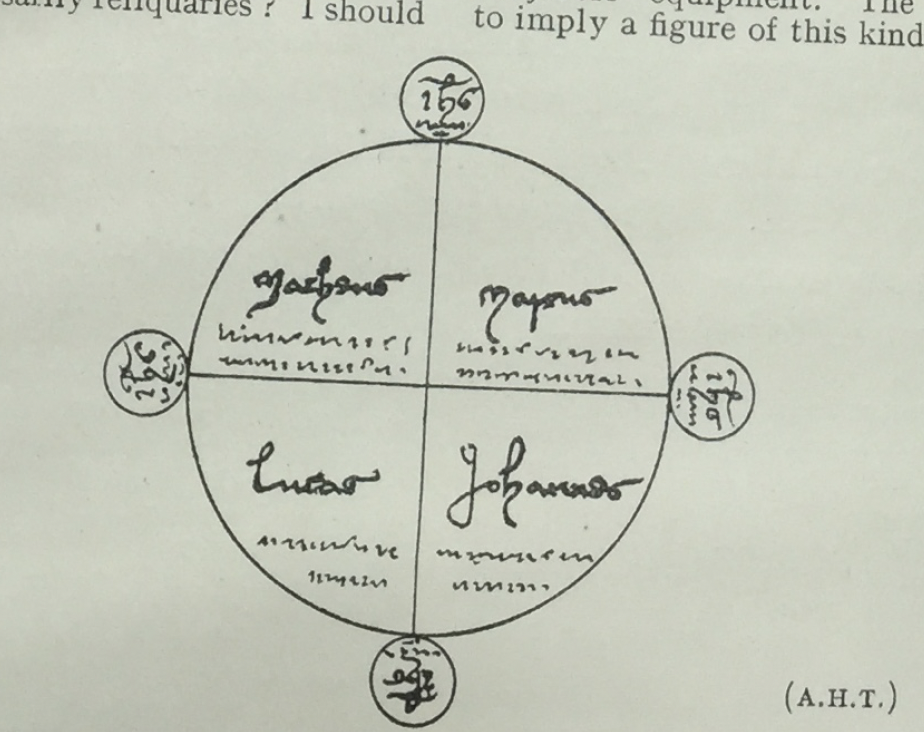

I think there can be no doubt that it was a circle with a cross drawn inside it at the points of which, where they meet the circumference, the reliquaries (monilia) were placed. I am not quite sure whether the passage does not mean that the names of the four gospels (i.e. the evangelists) and other sacred words were written in the quadrants of the circle. The magic circle plays a great part in a case of sorcery recorded in York Reg. Bainbridge and printed in Archaeol. Journal, xvi. It was here drawn on a huge sheet of parchment in a private house by an ingenious person who induced a number of people to combine with him in conjuring demons to reveal the hiding-place of a treasure at Mixendale Head, near Halifax. There is no mention of its being drawn with a cross or of a cross inscribed in it; it was copied from a conjuring book. It was inscribed however, "cum carecteribus et nominibus aliusque signis supersticiosis”; and one deponent, who arrived unexpectedly while the performance was going on, saw that the party “had a grete masse boke opyn afore theyme, and wrote oute what they wold”; cf. the “other sacred words” which the present spirit ordered his conjuror to bring with him. Are the monilia necessarily reliquaries? I should have thought that, in the present case, they might rather be medallions on which the titulus triumphalis was engraved, like the laminae of lead inscribed with figures of “Oberion,” “Storax,” and other spirits which formed part of the Halifax conjurors’ equipment. The text seems to imply a figure of this kind: — A.H.T.

III. Concerning the ghost of Robert the son of Robert de Boltby of Kilburn, which was caught in a churchyard. #

I must tell you that this Robert the younger died and was buried in a churchyard, but he had the habit of leaving his grave by night and disturbing and frightening the villagers, and the dogs of the village used to follow him and bark loudly. Then some young men of the village talked together and determined to catch him if they possibly could, and they came together to the cemetery. But when they saw the ghosts they all fled with the exception of two. Of these one, called Robert Foxton, seized him at the entrance to the cemetery and placed him on the kirkstile while the other cried manfully, “Keep him fast until I come to you!"

The first one answered, “Go quickly to the parish priest that the ghost may be conjured, for with God’s help I will hold firmly what I have got until the arrival of the priest.” The parish priest made all haste to come, and conjured him in the name of the Holy Trinity and in the virtue of Jesus Christ that he should give him an answer to his questions. And when he had been conjured he spoke in the inside of his bowels, and not with his tongue, but as it were in an empty cask,17 and he confessed his different offences. And when these were made known the priest absolved him but charged those who had seized him not to reveal his confession in any way; and henceforth as God willed he rested in peace.

It is said, moreover, that before his absolution he would stand at the doors of houses and at windows and walls as it were listening. Perhaps he was waiting to see if anyone would come out and conjure him and give help to him in his necessity. Some people say that he had been assisting and consenting to the murder of a certain man, and that he had done other evil things of which I must not speak in detail at present.

IV. #

Moreover the old men tell us that a certain man called James Tankerlay, formerly Rector of Kirby, was buried in front of the chapter house at Byland, and used to walk at night as far as Kirby, and one night he blew out the eye of his concubine there. And it is said that the abbot and convent caused his body to be dug up from the tomb along with the coffin, and they compelled Roger Wayneman to carry it as far as Gormyre. And while he was throwing the coffin into the water the oxen were almost drowned for fear.18 God forbid that I be in any danger for even as I have heard from my elders so have I written. May the Almighty have mercy upon him if indeed he were of the number of those destined to salvation.

V. #

What I write is a great marvel. It is said that a certain woman laid hold of a ghost and carried him on her back into a certain house in presence of some men, one of whom reported that he saw the hands of the woman sink deeply into the flesh of the ghost as though the flesh were rotten and not solid but phantom flesh.19

VI. #

Concerning a certain canon of Newburgh who was seized after his death by [blank].

It happened that this man was talking with the master of the ploughmen and was walking with him in the field. And suddenly the master fled in great terror and the other man was left struggling with a ghost who foully tore his garments. And at last he gained the victory and conjured him. And he being conjured confessed that he had been a certain canon of Newburgh, and that he had been excommunicated for certain silver spoons which he had hidden in a certain place. He therefore begged the living man that he would go to the place he mentioned and take them away and carry them to the prior and ask for absolution. And he did so and he found the silver spoons in the place mentioned. And after absolution the ghost henceforth rested in peace. But the man was ill and languished for many days, and he affirmed that the ghost appeared to him in the habit of a canon.20

VII. #

Concerning a certain ghost in another place who, being conjured confessed that he was severely punished because being the hired servant of a certain householder he stole his master’s corn and gave it to his oxen that they might look fat; and there was another thing which troubled him even more, namely that he ploughed the land not deeply but on the surface, wishing his oxen to keep fat; and he said there were fifteen spirits in one place severely punished for sins like his own which they had committed. He begged his conjuror therefore to ask his master for pardon and absolution so that he might obtain the suitable remedy.

VIII. #

Concerning another ghost that followed William of Bradeforth and cried “How, how, how,” thrice on three occasions. It happened that on the fourth night about midnight he went back to the New Place from the village of Ampleforth, and as he was returning by the road he heard a terrible voice shouting far behind him, and as it were on the hill side; and a little after it cried again in like manner but nearer, and the third time it screamed at the cross-roads ahead of him; and at last he saw a pale horse and his dog barked a little, but then hid itself in great fear between the legs of the said William. Whereupon he commanded the spirit in the name of the Lord and in virtue of the blood of Jesus Christ to depart and not to block his path. And when he heard this he withdrew like a revolving piece of canvas with four corners and kept on turning. So that it seems that he was a ghost that mightily desired to be conjured and to receive effective help.21

IX. Concerning the ghost of a man of Ayton in Cleveland. #

It is reported that this ghost followed a man for four times twenty miles, that he should conjure and help him. And when he had been conjured he confessed that he had been excommunicated for a certain matter of sixpence; but after absolution and satisfaction he rested in peace. In all these things as nothing evil was left unpunished nor contrariwise anything good unrewarded, God showed himself to be a just rewarder.

It is said, too, that the ghost before he was conjured threw the living man over a hedge and caught him on the other side as he fell. When he was conjured he replied, “If you had done so first I would not have hurt you but here and there you were frightened and I did it."22

X. How a penitent thief, after confession, vanished from the eyes of the demon. #

It happened formerly in Exeter23 that a ditcher, a hard worker and a great eater, lived in the cellar of a great house which had many cellars with connected walls but only one living room. The ditcher when he was hungry, used often to climb up into the living room,and cut off slices from the meat that was there hung up, and cook them and eat them, even if it were Lent. And the lord of the house, seeing that his meat was cut, examined his servants concerning the matter. And as they all denied and cleared themselves by oath, he threatened that he would go to a certain sorcerous necromancer and make enquiry through him into this wonderful event.

When the ditcher heard this he was much afraid and went to the friars and confessed his crime and received the sacrament of absolution. But the lord of the house went as he had threatened to the necromancer, who anointed the nail of a small boy, and by incantation asked him what he saw. And the boy answered, “I see a serving man with clipped hair.” The necromancer said, "Conjure him, therefore, to appear to you in the fairest form that he can and so he did. And the boy said, “Behold I see a very beautiful horse. And then he saw a man in a form like that of the ditcher,climbing up the ladder and carving the meat with the horse following him And the clerksaid, "What are the man and the horse doing now And the child said, “Look, he is cooking and eating the meat. And when he was asked again, “What is he doing now?” the little boy answered, “They are going both of them to the church of the friars, but the horse is waiting outside, and the man is going in, and he kneels and speaks with a friar who places his hand on his head.” Then the clerk asked of the boy, “What are they doing now?” and he answered, “They have both vanished from my eyes and I can see them no longer, and I have no idea where they are.”

XI. Concerning a wonderful work of God, who calls things which are not as though they were things which are, and who can act when and how he wills; and concerning a certain miracle. 2425 #

It has been handed down to memory that a certain man of Cleveland, called Richard Rowntree, left his wife great with child and went with many others to the tomb of Saint James. And one night they passed the night in a wood near to the King’s highway. Wherefore one of the party kept watch for a part of the night against night-fears, and the others slept in safety. And it happened that in that part of the night, in which the man we speak of was guardian and night watchman, he heard a great sound of people passing along the King’s highway. And some rode sitting on horses and sheep and oxen, and some on other animals; and all the animals were those that had been given to the church when they died .26

And at last he saw what seemed a small child wriggling along on the ground wrapped in a stocking.[^XI2] And he conjured him and asked him who he was, and why he thus wriggled along. And he made answer, “You ought not to conjure me for you were my father and I was your abortive son, buried without baptism and without name.”

And when he heard this the pilgrim took off his shirt and put it on his small child and gave him a name in the name of the Holy Trinity, and he took with him the old stocking in witness to the matter. And the child when he had thus received a name jumped with joy and henceforth walked erect upon his feet though previously he had wriggled. And when the pilgrimage was over he gave a banquet to his neighbours and asked his wife for his hose. She showed him one stocking but could not find the other. Then the husband showed her the stocking in which the child was wrapped and she was astonished. And as the midwives confessed the truth concerning the death and burial of the boy in the stocking a divorce took place between the husband and the wife in as much as he was the godfather of the abortive child. But I believe that this divorce was highly displeasing to God.272829

XII. Concerning the sister of old Adam of Lond and how she was seized after her death according to the account given by old men. #

It must be understood that this woman was buried in the churchyard of Ampleforth, and shortly after her death she was seized by William Trower the elder, and being conjured she confessed that she wandered in his road at night on account of certain charters which she had given wrongfully to Adam her brother. This was because a quarrel had arisen between her husband and herself, and therefore she had given the papers to her brother to the injury of her husband and her own children. So that after her death her brother expelled her husband from his house, namely from a toft and croft in Ampleforth with their appurtenances and from an oxgang of land in Heslarton and its appurtenances, and all this by violence. She begged therefore this William to suggest to her brother that he should restore these charters to her husband and her children and give back to them their land, for that otherwise she could by no means rest in peace until the day of judgment.

So William, according to her commands, made this suggestion to Adam, but he refused to restore the charters, saying, “ I don’t believe what you say." And he answered, " My words were true in everything; wherefore if God will you shall hear your sister talking to you of this matter ere long."

And on another night he seized her again and carried her to the chamber of Adam and she spoke with him. And her hardened brother said, as some report, “If you walk for ever I won’t give back the charters. Then she groaned and answered, “May God judge between you and me. Know then that until your death I shall have no rest; wherefore after your death you will walk in my place."

It is said moreover that her right hand hung down, and that it was very black. And she was asked why this was, and she answered that it was because often in her disputes she had held it out and sworn falsely. At length she was conjured to go to another place on account of the night-fear and terror which she caused to the folk of that village. I ask pardon if by chance I have offended in writing what is not true. It is said, however, that Adam de Lond, the younger, made partial satisfaction to the true heir after the death of the elder Adam.

Topographical Notes. #

The topography of the stories involves a few problems which it is difficult to solve with exact accuracy. The following notes have been compiled with the aid of Mr. William Brown, D.Litt., F.S.A., whose intimate knowledge of the district and its place-names has made it possible to suggest clues to the less obvious places mentioned.

I. To judge by the mention of Rievaulx in the title, the locality of the story may be fixed near the abbey; but the allusion to the beck is too general to afford any clue to its identity.

II. The scene is on the way from Gilling to Ampleforth, and the beck must therefore be the Holbeck, which is crossed by the present road from Gilling to Oswaldkirk, just north of Gilling railway station. The other places named are “Hoggebek” and “Bilandbanke,” which the hero of the story suggests as places of retirement for the ghost until his errand is accomplished. The nearest stream which can be identified with “Hoggebek” is the Hodge Beck, some seven or eight miles to the north-east, which runs through the ravine below Kirkdale church and joins the Dove, a tributary of the Rye, three miles south of Kirkby Moorside. “Bilandbanke” may be the steep hill slope above Byland Abbey, but it may refer equally to the side of the Rye valley below Old Byland. In the second case, the ghost would have to go about the same distance as to the Hodge Beck. Why it enjoyed the prospect of banishment to Byland Bank more than to the Hodge Beck must be left to conjecture.

III. Kilburn and Boltby, from which the Robert of the story took his name, afford no difficulty.

IV. The form “Hereby” points to Cold Kirby, between Sutton Bank and Old Byland. The church of Cold Kirby, however, was appropriated to Byland Abbey and served by a curate, so that James Tankerlay cannot have been its rector. Kirby Knowle, on the other hand, which lies two miles north of Feliskirk, at the foot of Boltby Moor, was a rectory ; and, although it had no connection with Byland, this is no bar to the possible burial of its rector in the abbey, which may have granted him the privilege of confraternity. The episcopal registers at York do not record one of this name as rector of Kirby Knowle ; and of the curates of Cold Kirby there is no record. Gormire, the tarn below Sutton Brow, is nearer to Cold Kirby than to Kirby Knowle; but this proves nothing. Kirkby Moorside might be meant ; but the incumbent there was a vicar, the church had no connection with Byland, and the taking of the body to Gormire in the opposite direction, makes this conjecture unlikely. The use of the form “ Hereby ” by a writer with local knowledge is decidedly in favour of Cold Kirby, and the description of Tankerlay as rector may be a mere inaccuracy.

VI. Newburgh Priory, founded by Roger Mowbray for Austin canons, lies south-west of Coxwold. The mention of the “master of the ploughmen indicates that the scene took place upon the priory lands.

VIII. Bradeforth, from which William took his name, is probably a mistaken form of Brideforth, Briddeforth (Birdforth) . Novus locus was most likely on the road between Ampleforth and Byland Abbey. The road ran along or under a hill-side, and the mention of cross-roads points to the neighbourhood of Wass, a hamlet which has grown up round a cross-roads. The ordinary English word translated by “Novus locus” is Newstead, most commonly used to denote the site of a monastery: cf. Newstead in Sherwood, Newstead on Ancholme, Newstead by Stamford. Oldstead lies west-north-west of Byland Abbey, and Oldstead Grange marks the site of a grange of the monastery. Oldstead implies the existence of a Newstead not far off; and, although the name Newstead does not survive to-day in those parts, it is very probable that there was a farm or grange of that name near Byland Abbey. It may be added that the site of the abbey and its immediate precincts might well be called “Novus locus” as distinguished either from the older settlement at Oldstead or from the previous sites of the monastery at Old Byland and Stocking.

IX. Ayton in Cleveland is Great Ayton, near Stokesley,

X. This story seems to come from another part of England, if Exon (Exeter) is the right reading.

XI. The scene of the story is uncertain, and it may have happened anywhere on the way to Santiago.

XII. The persons in this story might doubtless be identified from Subsidy rolls, but unfortunately none of those which would be most likely to help are in print. Lond is probably Lund, E.R.; but the name occurs in Lund House and Lund Forest, in the parishes of Lastingham and Kirkby Misperton respectively. Heslarton is, of course, Heslerton, E.R., between Malton and Scarborough.

Notes upon Tale XI #

1. The Latin word translated ‘stocking’ in the text of this story is caliga. As this word is still occasionally rendered, when found in medieval documents, in its classical sense of ‘boot’ it may be noted here that in post-classical times it was specially applied to cloth hose, the habitual form of medieval stocking. Among the garments enumerated in the Rule of St. Benedict, cap. lv, as sufficient for the monk are indumenta pedum : pedules et caligas, i.e. sandals and hose. As Dom Delatte remarks in his Commentary upon the Rule (trans. McCann, p. 348), the actual meaning of this passage perplexed the commentators of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; and he himself appears inclined to transpose the meaning of the two words.

Ducange, s.v. Caliga, gives abundant references, but no positive definition. A passage, however, in the Constitutiones Lanfranci (ap. Wilkins, Concilia, i, 359), dealing with the laying out of bodies of dead monks, is quite explicit: calcietur caligis supradicto panno factis, usque ad genua attingentibus, et nocturnalibus. Here the nocturnales are the monk’s shoes for night wear, while the caligae are cloth hose reaching to the knees. Cf. in this context the direction in Liber Eveshamensis (Henry Bradshaw Soc., vi, col. 124): Camerarius debet habere preparatos nocturnales et staminiam quam antea non habebat indutam et caligas.

These texts are noted by Dr. J. T. Fowler in the glossary appended to Durham Account Rolls (Surtees Soc., ciii, p. 899), where he defines Caligae as ‘socks, or stockings of some kind, sometimes perhaps soled.’ That their material was cloth is clearly shown by several references in the rolls, e.g. ibid., c, p. 518: in … panno empt. pro caligis inde faciend.; p. 553: in garniamento T. fatui cum 14 ulnis pro caligis tondendis ; and especially p. 536: in 15 uln. panni diversi coloris emp. in nundinis Dunelm. pro caligis inde jaciendis.

Dr. G. G. Goulton notes (Social Life in England, p. 78) the common misapprehension of the meaning of caliga, and refers to passages in Thorold Rogers’ History of Agriculture and Prices in England in confirmation of the true meaning. Further, Promptorium Parvulorum (Camden Soc., i, 248, with a long note, and E.E.T.S., col. 227) has ‘Hose. Caliga’: see also Catholicon Anglicum (E.E.T.S., p. 189): ‘Hose. Caliga, caligula,’ followed by the verse Sunt ocrie, calige quos tebia portat amictus. Here ocreae are high boots worn over the cloth hose; cf. Prompt. Paw. ut sup., i, 45: ‘Bote for a mannys legge. Bota. Ocrea’; and col. 44: ‘Boote for the legg. Bota ocrea.’

Such boots were made of leather; see Durham Account Rolls ut sup., ciii, p. 587: 1 pare botarum de Cordwan pro d’no priore. With regard to the wearing of boots (ocreae) by canons regular see the indult (Cal. Papal Letters, vi, 158), by which the canons of Worksop were permitted to wear shoes (sotularia) instead of boots; see also Visitations in the Diocese of Lincoln (Lincoln Record Soc.), i, 32, note, and ii, 165, 168, for their obligation to wear boots. Dr. M. R. James quotes Blackman’s account of Henry VI’s dress: he wore caligas, ocreas, calceos omnino pulli coloris, which hose, boots, and shoes appear to be distinguished. Although, as Dr. James remarks, the writer of these stories cannot be supposed to have drawn very line distinctions between ocrea and caliga, yet the distinction is well supported, and it is more reasonable to suppose that the child’s body was wrapped in a cloth stocking than stuffed into a high leather boot. — A.H.T.

2. The occurrence of the name Rowntree in this story has been communicated to Mr. Arthur Rowntree, of York, in view of a possible connection between his family and the neighbourhood of the story. He answers that his pedigree can be traced back to a certain William Rowntree, of Riseborough, near Pickering, born in 1728, and that the family may have come from Stokesley, where there are some six or seven hundred Rowntree names in the parish register. Rowntree wills occur in the Probate Registry at York in 1543, 1553, and 1558; but there appears to be no record of any association with this particular district.

So in No. II a ghost is said to appear “in specie dumi” (as I read it), i.e. of a thorn bush. In several of these stories the ghosts are liable to many changes of form. — M.R.J. ↩︎

Great pains have been taken throughout to conceal the name of the ghost. He must have been a man of quality whose relatives might have objected to stories being told about him. — M.R.J. ↩︎

In the Danish tales something like this is to be found. Kristensen Sagn og overtro 1866, No. 585: After seeing a phantom funeral “the man was wise enough to go to the stove and look at the fire before he saw (candle- or lamp-) light. For when people see anything of the kind they are sick if they cannot get at fire before light.” Ibid., No. 371.: “He was very sick when he caught sight of the light.” The same in No. 369. In Part II of the same (1888), No. 690: “When you see anything supernatural, you should peep over the door before going into the house. You must see the light before the light sees you.” Collection of 1883, No. 193: “When he came home, he called to his wife to put out the light before he came in, but she did not and he was so sick they thought he would have died.” These examples are enough to show that there was risk attached to seeing light after a ghostly encounter. — M.R.J. ↩︎

This rather suggests that you might be reckoned to have kept a mass if you came only in time for the last gospel. — A.H.T. ↩︎

Defaming (defamatio or diffamatio) is the formal accusation of crime which renders a man liable to spiritual censure, and puts him in a state of inf amici from which he must free himself by compurgation or by establishing a suit against his defamer in the spiritual court. The infamia of a dead man (resting here on his own acknowledgment) would place him outside the privilege of Christian burial and lead to the disinterment of his remains. Cf. the posthumous defamation and disinterment of Wycliffe for heresy. - A.H.T. ↩︎

I suppose in order that the ghost might not haunt the road in the interval before the tailor’s return. — M.R.J. ↩︎

The reluctance of the priest at York to absolve and the number of advisers called in testify to the importance of the case.— M.R.J. ↩︎

The conduct of the officious neighbour who insists upon being informed of the tailor’s assignation with the ghost and then backs out of accompanying him is amusing. — M.R.J. ↩︎

Whether a circle enclosing a cross or a circle drawn with a cross I do not know. – M.R.J. ↩︎

See also A.H.T’s note and illustration at the end of this story. – N.B.Z. ↩︎

I think the allusion is to the pictures of the Three Living and the Three Dead so often found painted on church walls. The Dead and Living are often represented as Kings.— M.R.J. ↩︎

One of the best examples (though only the “Trois Vifs” remain) of this kind of painting is over the north doorway at Lutterworth, and there is a very good example at Paston, Norfolk. — A.H.T. ↩︎

The need of a prescription for healing the tailor was due to the blow in the side which the raven had given him. — M.R.J. ↩︎

This does not seem logically to follow upon the prohibition to tell the ghost’s name. I take it as advice to the tailor to change his abode. — M.R.J. ↩︎

I do not quite understand how this fire business worked; the Danish cases cited are not quite explanatory. Presumably the spirit, whom he had helped, meant that the tailor need not look at the fire as a precaution when he went home, now that all was well, and that all he need do was to keep his thoughts under control. The force of “for this night at least” seems to be that it would be well to look at the fire another night; the bullock was still about, and might be met again. — A.H.T. ↩︎

The text has been reparagraphed from the original, for better legibility in an online format – N.B.Z ↩︎

A picturesque touch! These ghosts do not twitter and squeak like those of Homer. — M.R.J. ↩︎

When Wayneman was throwing the coffin into Gormire the oxen which drew his cart almost sank in the tarn from fear. This, I suppose, is the sense of this rather obscure sentence. — M.R.J. ↩︎

This is most curious. Why did the woman catch the ghost and bring it indoors ? M.R.J. ↩︎

A daylight ghost it seems. The seer and the head ploughman are walking together in the field. Suddenly the ploughman has a panic and runs off, and the other finds himself struggling with a ghost. Probably the Prior had excommunicated the stealer of the spools whoever he might be, without knowing who he was, as in the case of the jackdaw of Rheims. — M.R.J. ↩︎

For three nights William of Bradford had heard the cries. On the fourth he met the ghost. And I suspect he must have been imprudent enough to answer the cries, for there are many tales, Danish and other, of persons who answer the shrieking ghost with impertinent words, and the next moment they hear it close to their ear. Note the touch of the frightened dog. — M.R.J. ↩︎

The ghost throws him over the hedge and catches him as he falls on the other side. So the Troll whose (supposed) daughter married the blacksmith, when he heard that all the villagers shunned her, came to the church on Sunday before service, when all the people were in the churchyard, and drove them into a compact group. Then he said to his daughter, “Will you throw or catch?” “I will catch,” said she, in kindness to the people. “Very well, go round to the other side of the church.” And he took them one by one and threw them over the church, and she caught them and put them down unhurt. ‘‘Next time I come,” said the Troll, “ she shall throw and I will catch — if you don’t treat her better.” Not very relevant, but less known than it should be. - M.R.J. ↩︎

The word is Exon. Is it possible that some local name is concealed under it? If it really refers to Exeter it is the only story that does not refer to the district. ↩︎

For my (much-embellished) retelling of this story, see The Baby in the Boot at my blog Multo(Ghost). – N.B.Z. ↩︎

This page is difficult to read, blurred, and the writing in places gone. — M. R. J. ↩︎

There are multitudinous examples of the nightly processions of the dead, but I do not know another case in which they ride on their own “mortuaries” (the beasts offered to the church or claimed by it at their decease); it is a curious reminiscence of the pagan fashion of providing means of transport for the dead by burying beasts with them. — M.R.J. ↩︎

Evidently the wife was not accessory to the indecent burial of the child, and the sympathy of the writer is with her. The divorce does seem superfluous, since though sponsors were not allowed to marry, here is but one sponsor; but I know not the canon law. — M.R.J. ↩︎

I cannot conceive what the grounds of the divorce were, unless it could be argued that the father, by standing godfather to his own child after marriage, entered into a relationship which was irregular. Parents could not be sponsors for their children; and if the story is true it may have been held that this irregular act dissolved the marriage,’ and that, in taking upon him the sponsorship, he renounced his rights as a husband. On the face of it this was the view taken; the incident was so remarkable that it must have been hard to cite precedent. - A.H.T ↩︎

As I mention in an afterword to “The Baby in the Boot,” there is a Scandinavian ghost called the myling, the ghost of an unbaptized child–often implied to be an infanticide victim. If Richard suspected his wife of such a deed (after all, he was likely gone a really long time), that may be why he divorced her. – N.B.Z. ↩︎