When the last of the mail-bags had been opened; when, on the chock-a-block tables, the sorted letters stood in serried, marshalled rows, young Fraser and I carried them across to the swing-seated postmen's benches and dumped them down in handfuls, cards and cakes and children's toys alike. Then only, did we pull chairs to the frosty fire, set feet on the iron over-part of the stove, and sip our parboiled, milkless tea from the long jugs that served at once as teapot and as cup.

Presently young Fraser swung round and pointed ever his shoulder at the sorting tables we had cleared. For all that was Christmas Eve never a letter lumbered them; it might have been a mere commonplace weekday, so well had things got through. No wonder he was in ecstasies with himself. We were level with, even ahead of, our work. And before us, till up the town hill and through the drifted snow the motor-mail should grunt and puff, there lay an hour—a whole sixty minutes of unexpected rest, the gorgeous fruit of what young Fraser called "wiring in." He was a splendid boy to work with—the best I ever knew. Post Office blood was in him to the heart's core—three generations of it, as he loved to boast.

"By Gad, Morell," he cried, "it's magnificent! We've never managed so well before. I wish to goodness the chief were here. He wouldn't talk so much about the inferiority of the present generation if he could see them!" And, tilting back his chair, he waved a hand vaingloriously at the vacant tables. "Never a letter on them—and an hour to spare !"

Then, because I answered nothing, because he felt me wanting in enthusiasm, he leaned quickly forward, so that the front legs of his chair met the floor again; and as with its passage his body came once more level with mine, his left hand clumped me heavily on the back and he triumphed into "Not a single letter on the tables!"

Crash — crackle and crash — on to the stone hearth went the jug that I was carrying to my lips; a brown stream trickled out on to the carpetless boards beyond. I started to my feet with a cry that came quicker than the thought of repression, and leaned against the mantelpiece, nervous and a-shake.

Young Fraser stared at me in amazement. Wonder and regret chased across his face, going and coming, again and yet again, like stage armies with their recurring exits and entrances. But when he proffered me his own jug and began to blurt out apologies for what he called thoughtlessness, I waved the brew away and cut his explanations short.

"It's not your fault at all! "I said, still leaning against the mantlepiece and trying to pull myself together a bit. "It's the fault of my beastly nerves, and too much night duty—and much too much strong tea. I've been in an awful state just lately !"

Young Fraser nodded his sympathy. "I've noticed it," he said. "So have the other chaps. And we've been talking about it—and how bad you've looked this last week. Before that you were fit as a fiddle. But now——" And he waved expressive hands at me, as though to say, " If ever there was a wreck it's you !"

I nodded——and got back into my chair again. Fraser put some coal on the fire, and, before beginning to smoke, offered me a cigarette. I shook my head.

"I'm off my smoke," I explained. "I'm off my food. I'm off everything."

Fraser whistled, with averted face. But his silence seemed to me to invite confidence, and I took heart of grace to tell him all.

"Don't think I'm mad, or that I've been drinking or taking drugs," I began.

"As if I should," he interrupted; "as if I should. You're the very last chap to do anything of that sort. We all know that. And, besides, if you were you couldn't——"

"Win pots as I do, you mean?"

win pots:I think this is an expression for winning a round of poker. A reader comments that in their experience, "pots" usually means "cups, medals, awards for athletic or sporting prowess". This makes more sense than my guess.

"Exactly," he acquiesced. "That's just what I was going to say."

"Thank you," I answered. Then I blurted out quickly: "Jack, old man, I've seen a ghost."

Again the boy whistled, and this time he faced me fair and square. His eyes narrowed a little in a way they had when he looked at things hard or was at all in doubt, and I felt that he was wondering what to do with me. Then his eyes widened again, and he leaned back in his chair and said :—

"Suppose you tell me all about it. For there's nothing like getting things off your chest."

So, staring into the fire, resolutely avoiding his face, I began, because I knew it was the only way to make him believe and understand.

"It was last week, on night duty, about this time, in the office here. The sorting tables were clear, just as they are now. I had taken the letters round to the postmen's benches, and was going to have a sit down and a rest and a cup of tea. But before I did so I had another look at the sorting tables, just to see that I hadn't left anything on them, though I knew I hadn't. You know how one does that?"

"I know," said the boy at my side. "Just as a painter looks at a picture when he's finished it—as any man who's done a job looks when he's glad the job's done."

" Exactly. Well, just because I knew I'd left nothing on the tables I looked at them then. And on the top rack, standing against the criss-cross wire netting, I saw a letter. But it wasn't one of those I'd sorted. I knew that at once. Someone had put it there afterwards! Someone I couldn't see !"

Young Fraser laughed, and put a hand affectionately on my arm.

"What rubbish!" he said. " You'd overlooked it. There's nothing in that. And how on earth could you tell it wasn't one of the hundreds you'd just sorted? Your nerves were on edge and you're run down. It's enough to make a fellow jumpy, this old house and the dark corners and passages—and doors that make noises every time the wind blows, even though they're shut! You fancy things, that's what it is !"

"I wish I did," said I. "But this wasn't fancy, or anything like it. And what I saw wasn't an ordinary letter at all !"

Then, because the boy beside me made no answer, and I knew he was growing nervous—nervous of me and of what I might say or do—I broke sharply off and asked him a question.

"Jack," I said, "do you know what a Mulready envelope is?"

Before he could answer me—almost before the words were out of my mouth—a sound, such a sound as a human being might utter in the extremity of mental anguish, came to us across the room. It was a faint, moaning noise, a manner of hopeless wail; more than anything else a sob, but a sob of inexpressible distress.

Then it was that young Fraser ceased to listen to me with a cold, judicial air, and all his critical aloofness went, metamorphosed into a fear that his eyes mirrored and made plain.

"Good God! What's that?" he cried, and glanced nervously over his shoulder—half glanced only, as if he feared to see the thing for which he looked.

I drew my chair closer to young Fraser's. I knew the thing would pass, as it had passed a week ago that night. And I was glad to have by me a fellow-creature whose fear matched my own.

Fraser caught at the poker and stabbed the reddening coal to a blaze. Then he whispered fearfully in my ear: "What's a Mulready envelope?"

Only half conscious of what I said, my brain eager and my ears intent to catch the slightest sound, I whispered back my answer to the boy.

"When first the penny post came, and before stamps, as we know them, were used, the Government sold an envelope for carrying letters in. The charge for the envelope included cost of carriage as well—just like the plain embossed penny envelopes we sell to-day—and the envelope itself was designed by a great artist, Irish painter William Mulready designed the Mulready envelope. with all sorts of figures on its address side. I saw one once in a collection; they're awfully valuable now. Well, it was one of those that I found on the sorting-table a week ago."

Young Fraser shivered. Then, caught by a sudden idea, he threw out: "Perhaps someone sent it through the post by mistake—some poor person, or some schoolboy with an album, who didn't know its value?"

I shook my head, caught the boy's wrist, and held it as I said, slowly :—

"That might have been possible, if— if——"

"Well — well?" young Fraser helped me out.

If the envelope had been there."

"But you saw it—just now you said you did. What did you mean?"

"It was there," I answered; "but not to touch. It was intangible. I tried to take it in my hand, and I couldn't. And then——"

"And then?"

"I took my eyes off it for a second, and when I looked it was gone!"

Again young Fraser tried to find the natural cause.

"Perhaps your eyes were tired?" hehazarded. "Perhaps you'd been reading about a Mulready envelope and were out of sorts and fancied you saw one?"

I paused—to give my coming answer weight.

"I hadn't been reading about the sobbing—the sobbing such as we've heard tonight. And I hadn't been reading about the other things I saw afterwards."

"What other things?"

I looked at Fraser hard and long in my doubt. Somehow, for a reason that I couldn't fix or place, I could not bring myself to tell him. It wasn't fair to him—to him of all people. He, too, might see what I had seen—and know the thing for what it was. Then, as I stood there, doubtful and divided in mind, casting about for a decision that should best serve us both, a sudden cry tore through the silence, and young Fraser stood before the middle sorting-table and pointed.

There, on the top rack, resting against the criss-cross wires, was a letter! And we had left none. This time it was not my word alone, but the boy's to back it and to prove.

I stared at Fraser. Fraser, white as a sheet of paper, stared back at me. The same thoughts assailed us both. Was it an ordinary envelope—or was it—was it the Mulready ?

And then young Fraser, leaning forward, peering into the corner of the table's topmost rack—where, against the criss-cross wires, the letter stood—called wildly: "My God, it is—it is the Mulready. I can see the drawings quite plain and clear."

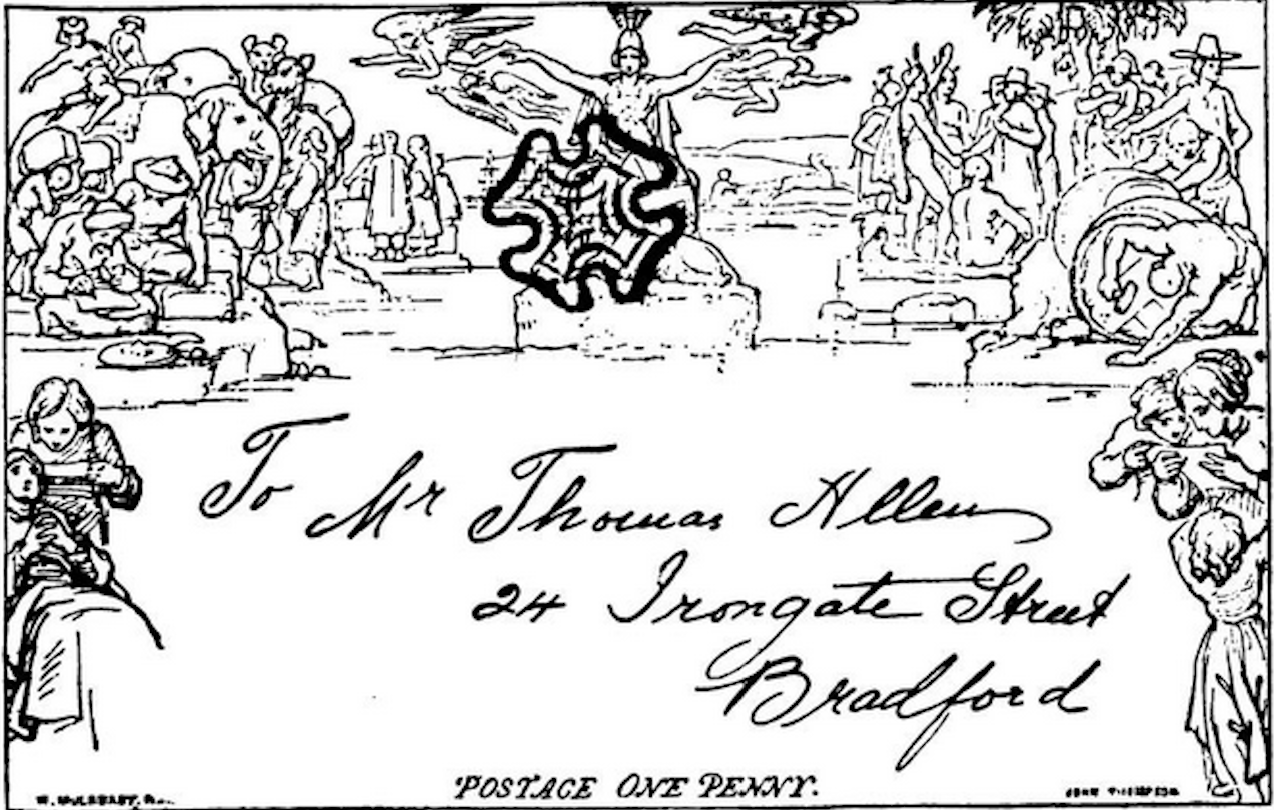

A Facsimile of the Mulready Envelope. Image Source

Though I had no doubt, though in my heart of hearts I felt that it was the self-same envelope that I had seen, yet, lest my tired eyes had tricked me, I, too, leaned forward and looked. I saw Britannia on her throne—Britannia, with circumvolent angels, and the elephant, and the flying deer, and the tall ships, and all the detail of the well-known design Color photo of a one-penny Mulready envelope. The Wikipedia page mentions that a certain paranoid faction of the public regarded the Mulready stationary as "a covert government attempt to control the supply of envelopes, and hence control the flow of information [sent through the mail]...." Sigh. ; and then, knowing that it was vain, I put out my hand and tried to grasp the letter. But before my hand could come at it, it seemed suddenly to fall — to fall through the unyielding wood of the sorting-table, so that, passing through the boarding of the floor, it disappeared wholly from our view. But I had had time to read the address—written in a flowing Victorian hand.

And from the far corner of the room there came to us once more the faint moaning noise, a manner of hopeless wail; more than anything else a sob, but a sob of inexpressible distress.

Because I knew what was going to happen I crooked my arm in young Fraser's, and clutched at the table's side and whispered quickly to him:—

"Hold up for a minute—it's coming—but it will pass." For God's sake don't give way!"

I saw him set his teeth and brace himself to bear; then with his free hand he pointed to the corner whence the sob had come.

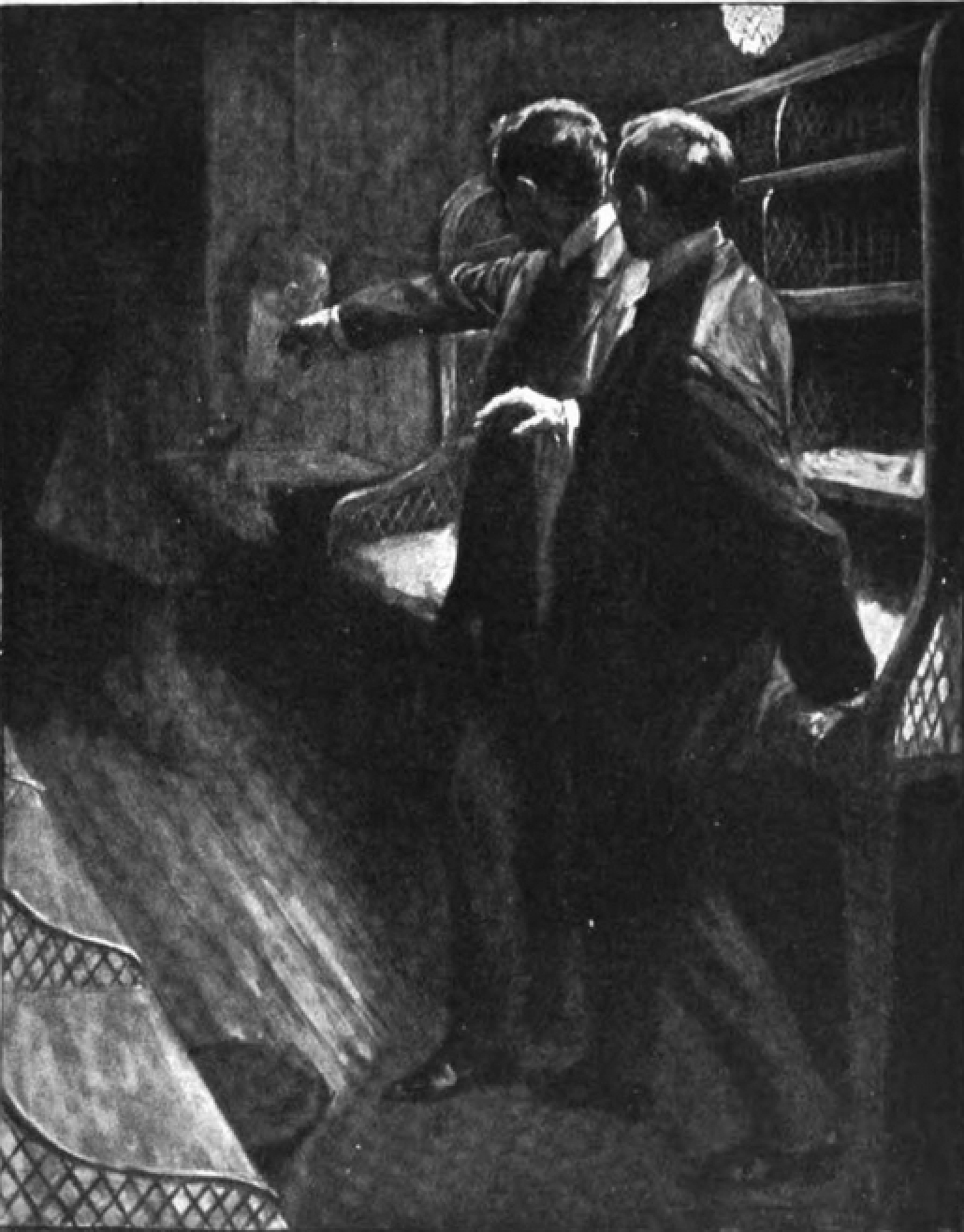

"Look!" he whispered. "Over there! It's in the office now !"

Slowly, out of the darkness of the far corner, silently, without sound of footfall or of breath, there came into the light the figure of a man—a man clad in such garments as one sees in prints and portraits of the late Queen's early reign. It wore a long blue-bottle coat of some dark stuff, while out of the canary-coloured vest a frilled shirt peeped; the trousers were tight and strapped beneath the boot; a high stock touched and almost covered the chin; on the coat itself a row of buttons sparkled and shone.

"'Look!' He whispered. 'Over there!'" Image Source

The figure went stooping—stooping always—and we could not see its face. But it seemed to be searching—searching unceasingly—till it came level with the locked letter-box that opened, cupboard-fashion, into the room, but whose key was on the ring I kept that week. It seemed to fumble vainly with the lock, to pull fruitlessly at the meeting of the double doors, to want to see within, as if something lay hidden that it could not find

Then, suddenly, it tried no longer, but turned and faced us as we stood by the tables. Above its head it raised deploring hands; once more the helpless wail divided the silence that surrounded us; again we heard the faint moaning noise, more than anything else a sob—a sob of inexpressible distress. And then young Fraser tore himself from my side and threw out his hands, as if between him and the pitiable figure there existed some inexplicable understanding—some strange sympathy that I could not share. And the Thing's face was the face of young Fraser himself.

"Yes! Yes!" and "Yes!" again he cried, and his voice, though firm and sure, was full of tears. It was as if he answered some question asked, but unspoken.

And it seemed that the answer was understood. For the features that were young Fraser's own lost their sadness and grew glad; the eyes, that had been heavy with weeping, seemed to smile, while the hands pointed to the floor beneath the tables. And as the boy's face flushed with understanding and his eyes grew glad too it slowly vanished and was gone—gone as that night a week back, when I had seen it in my solitude and fear. But then it had not smiled or done anything else but search and sob.

Young Fraser set his arms on the table nearest him, and on his arms he set his face, and I saw him shake like a man with ague. I stood, trying not to watch him, and presently he looked up, his hand on a steadying chair-back, and spoke.

"It was my great-grandfather!" he said, simply, and I knew that what he said was true. "He was once postmaster here, but they dismissed him on suspicion of stealing a letter—a letter with money in it that could never be traced. It's a skeleton in the family cupboard, and that's why I've always made out that I'm the third Fraser in the office. But I'm not—I'm the fourth. And we've a miniature of my great grandfather at home. I'm as like him as two peas, and they say I'm like him in character as well. So"—he faced me confident and sure—"so he came to me to help him, to clear him of the shame that won't let him rest. And I'm going to do it !"

Bold as the boy's assurance was, somehow I had no doubt, that he would make it good. And when I asked him how, he laughed, with the same glad eyes that were in the face of the Thing, and pointed to the floor as the Thing had pointed, and answered me:—

"The letter is there—underneath the tables; it slipped off them and fell through a chink in the boards!"

"But there's no chink there !" I cried.

"There was then," said young Fraser, calmly. "And when the office was refitted and altered, it got filled up. But we shall find the letter underneath!"

I looked at him, amazed at his confidence. "Why are you so sure?" I wonderingly asked.

"Because He told me," said young Fraser, smiling still. "We understood each other, He and I!"

So straightway, for all that it was Christmas Eve and work was yet to be done, we got the boards loosened and moved them, and looked for what young Fraser knew was there. Soon, groping with tongs beneath the spot where the letter had seemed to stand that night, he came on a dirty, grey thing in a crevice under the floor. He tugged a little over-forcefully, and I heard the noise that paper makes in tearing. Then he drew the dirty, grey thing up, still nipped by the delving tongs, and as it came clear of the crevice I heard the rattle of coins upon the floor. Following their sound, I found them. They were two guineas of late Georgian date. I gave them to young Fraser without saying a word.

"There were two guineas in the lost letter!" he triumphed. "That was why my great-grandfather was suspected." And he handed me the dirty grey paper to see.

There, looking at it beneath the gas, I knew it for what it was. Beneath the drab and dirt of seventy years I saw Britannia on her throne—Britannia, with circumvolent angels, and the elephant, and the flying deer, and the tall ships, and all the details of the design.

Then, standing at my side, looking over my shoulder, young Frasier said :—

"Read the address, if it is legible still."

I did as he asked.

"To Mr. Thomas Allen, 24 Irongate Street, Bradford."

It was the second time that I had read those words that night.

Annotations by Nina Zumel

Illustrations by A.J. Gough, for the original publication of this story in The Strand.