Little Johnny faces a lean Christmas, with no toys, no cheer, hardly enough food. Then, from some unseen world, comes----

The tinkle of a tiny bell, shaken vigorously by a scarlet-coated Salvation Army Santa at the curb, echoed cheerily through the frosty air. I stepped into the doorway of a little shop whose lights, peeping from behind panes festooned with greens and holly, shone out into the shabby thoroughfare.

For my numbed and tired limbs called for a moment or two of rest. Rest, beyond the reaches of the steadily falling snow which the wind from the not-distant river whipped into swirls before tossing it into drifts along the pavement. Rest, to recover a bit of energy to continue the gladsome task which had kept me on the move almost continuously since early morning.

"And his features--somehow they appeared familiar."

For it was Christmas Eve, and I had spent the day distributing gifts and money among those of the great city's needy whom I knew personally.

As I wiped the snow from eyes and dusted it from the fur about my throat, the little bell again sent forth its merry clatter.

I looked at the counterfeit Santa who stamped energetically about his kettle to keep up circulation in his body. But no hint of his personal discomfort could be noted in his twinkling eyes, or his mouth twisted into a grin behind his ill-fitting whiskers.

And, as one or another of the bundle laden crowd that trudged past him tossed a coin into the snow covered bottom of his kettle, there seemed to be music in the tone of his never failing,"Thank you! Merry Christmas!"

Anxious to do my bit toward keeping that particular pot boiling with a liberal contribution which would go toward providing a bumper Christmas dinner for the city's derelicts on the morrow, I opened my purse and reached deep with eager fingers. But I gasped a bit when they drew forth but two coins: a silver quarter and a nickel.

"Surely there must be some mistake," I thought. "There must be a bill or two hidden in some corner." But, though I searched each pocket carefully, not even a stray penny rewarded me. I had been even more liberal in my Christmas giving than I had supposed. All that remained was thirty cents.

And even that shabby sum would have to be divided. For between the little shop on the outskirts of a tenement-lined stretch of Murray Hill, in whose doorway I had sought temporary shelter, and my home in the middle reaches of Riverside drive, there lay several miles of slippery streets. I could not walk the distance. Unfatigued I would have hesitated to attempt the hike in the face of the storm which made all walking a real effort. But, already about "all in", I know I could not make my way on foot. The nickel must go for a subway ride which would carry me over a portion of my journey.

I dropped the smaller coin back into my purse. But, as I held the other, ready to toss it into Santa's yawning kettle, a new thought came to plague me—one which drove all other ideas temporarily from my mind.

I had not yet visited the Kelly tenement at the other end of Murray Hill. The little three-room flat in which lived the widow, Bridget Kelly, who eked out just sufficient by "day work" to maintain a home and feed and clothe herself and her five-year-old son, Johnny. What would Johnny think if I missed him?

Tears of vexation came to my eyes as I thought of them. For I was fond of Bridget, always hard working and uncomplaining. And of all my young friends, I loved Johnny most. For he was a manly fellow, ever planning and looking forward to the day when he would be old enough to "go to work and help Mother."

I would have given material help long ago—to both of them—but the proud Bridget would not permit. Kind words she welcomed. Charity she refused. She would continue to work and care for Johnny until he had been to school. And then—

But how could I have forgotten them? They had been foremost in my mind when I left home that morning. For three years I had done what I could to make Johnny's Christmas brighter—to prove that Santa Claus remembered the children of the tenements as well as those of the avenues. My lapse of memory hurt, Even though I had been climbing stairways since early morning, though time after time I had replenished my stock of toys and candy, though I had spent hours planning the distribution of gifts with wan and work-worn mothers, I should not have forgotten Johnny.

Then, as many times, since I first had become acquainted with Mrs. Kelly and her little son, I wished that, by some freak of chance, they could be placed in possession of a secret hoard of money I was certain that old house contained. Money which had been hidden there by a former owner. That cache probably would be sufficient to place the plucky widow and her boy beyond want for a long time.

But I put aside my wish in order that I might consider the more material need of the present. It was not too late, even then, to make good for my lapse. I glanced at my watch. Only nine o'clock. Bracing myself for the long walk to the nearest subway station, I plunged out into the storm. My quarter plumped into the snow at the bottom of Santa's kettle as I reached the curb. And his cheery, "Thank you, lady! Merry Christmas!" followed me as I dodged across the roadway through lumbering, swerving vehicles.

It was not until I had edged my way into a seat in the car of a northbound train that I had opportunity to think of anything but the storm which I had breasted, of how to keep from slipping, and keep the snow from my eyes so that I could note the streets I traversed. But, when I recovered my wits, I at once remembered Johnny and the necessity of preventing bitter disappointment coming to him on the morrow. And the thought seemed to give me new strength and courage. I was eager to carry on until I had fulfilled the task to which I had set myself.

Then, probably because of old associations connected with the tenement in which the Kellys lived, I recalled the first Christmas Eve I could remember. For it had been spent in the self same structure. But things were so different then, when I was four years old. In those days Murray Hill still retained its pristine glory as Manhattan's mid-town social centre. Only a scattering of shops had encroached. And the tall, grim loft buildings had not yet appeared to shut out the air and sunshine. Refinement, culture and quiet had not yet yielded to the demands of manufacture and trade, the kind which always brought squalor, dingy tenements, and rumbling trucks in its wake.

In that period the tenement in which Johnny and his mother lived was a proud, old house of ornate design, five stories in height and with a scrolled balcony of iron, stretching across its parlor floor.

And there had lived the Huntingtons, the universally beloved Archer Huntington, and his beautitul wife, Dolly. Archer had been a great shipping master and a financial power in The Street; a man of enormous wealth for those days. But, with all their material prosperity, the Huntington home had lacked the one thing to make it complete—a child.

One had come—a little boy. But he had been taken away before a year had passed. There had been no other. However, though childless, Archer and his wife had loved children with a passion which surpassed all other interests for them. Their home always was the playground for the little ones of their relatives and friends. And Dolly, despite the frail, little body which made her almost an invalid, went about daily into the homes along the waterfront looking after the needs of the children of the poorer families.

Archer backed her splendidly in these efforts. But his big days came with Christmas, when he could gather children about him to his heart's content. The day before Christmas, in an old hall far down in the Bowery, he held open house for the youngsters of the city's poor, where there was a gigantic tree ablaze with colored candles and long tables, heaped high with goodies; and ice cream and candy to follow.

However, it was after the feast when old Archer was truly in his element. For then, clad in scarlet cap and fur-trimmed coat, with shining boots that reached almost to his hips, he played Santa Claus, heaping toys into the arms of each eager child as it filed past him. And he looked the part. For he was short and stout, with a waistline that stretched the belt about his gaily colored doublet. And framing his laughing eyes and ruddy cheeks was a mass of snowy whiskers that made artificial disguise unnecessary.

In the evening, in his great stone mansion just off the avenue, there would be another celebration—a splendid Christmas Eve party, to which would flock the children of his friends. And again he would play Saint Nick. and help happy Dolly distribute the creams and favors and pass about the presents, taken from a glittering tree, with each little one's name written upon the wrapper. And it was at Santa Claus Huntington's that I attended my first Christmas party. I was an excited, wide-eyed little miss whose great hope was fulfilled when Santa Claus Huntington himself gave me a big doll with flaxen hair that could say "mamma."

However, that was my only party there. For, the following summer Archer and his wife steamed away in a yacht for ports in the South Seas, where it was hoped the warmer breezes would restore the roses to Dolly's cheeks. But the yacht never reached its destination. And though my father, Archer's life-long friend and business associate, conducted a world-wide search for it, neither the boat nor its passengers were ever heard of again.

My father, as well as others of Archer's intimates, knew that, somewhere in the house, he always kept a considerable store of ready cash for emergencies—such as his own and Dolly's charities, or to aid less prosperous friends in need of loans, for which no papers would be signed or interest exacted. This hiding place, known only to him, was hunted for repeatedly, but never uncovered.

Then followed long years in which the old house remained closed and its windows boarded up. The neighborhood changed. Ugly business structures elbowed their way in. Workmen descended upon the old houses that remained, altering them inside and out, dividing the great rooms into smaller ones—making them over into beehives for humans. And into these tenements moved those who were compelled to count their pennies—the overflow of the poor from Five Points, Hell's Kitchen and Mulberry Bend.

Finally the Huntington estate was disposed of. My father purchased the old house, hoping, for sentimental reasons, to rent it as it stood, thereby preserving its outward appearance at least. But he had failed in that objective. No one wanted a whole house in that teeming tenement district. So, though my father continued his ownership, he permitted it, like its neighbors, to be rebuilt into small flats.

In those years my mother had died, leaving only me to care for Dad. But, though his hair became thin and frosted, though the old fire in his eyes was reduced to smouldering embers and he laughed only when he and I were alone in the great library at night, the blow of losing the woman who had stood by him through his early struggles did not sour him.

In Archer's time, Dad always had assisted him in carrying out his plans to make children happy, though he always kept in the background. After his partner disappeared, he continued to carry on the labor of love, but in his own way. His nature would not permit him to play Santa Claus. But on each day before Christmas, with his pockets bulging with bills and a car loaded with toys, he visited the homes of every employee of his bank and personally distributed his gifts to the children and left money for their entertainment at a theatre or elsewhere on the holiday.

Today, as usual, he must have been out among his little friends. I hoped he wasn't very tired. For Dad was getting older. The spring in his step—

The raucous shout of the train guard roused me from my reverie. Although I did not catch his jumbled words, I knew instinctively I had reached the station nearest my home. And, joining the jostling crowd, I left the train, climbed the sodden steps and again headed out into the storm which had increased in intensity.

But, still buoyed up with thoughts of what I had planned to do for Johnny that night, I made speed over the few blocks which brought me to where I knew Dad would be waiting—probably anxious because I was returning later than customary.

As Judson swung wide the front doors, I tossed my dripping coat and hat upon a chair and burst into the library with a cry of, "Dad, Dad, where are you?"

But I was sorry I had been so precipitate. For he had been dozing, in his big chair before the fire-place, one hand shading his eyes. And I noted those eyes were tired—very, as with "Tony, you little gadabout, where have you been until this unearthly hour?" he came to his feet, arms outstretched, a great smile driving the wrinkles of fatigue from his features.

"Sit down, Dad,"—after the first big hug and kiss. I forced him gently back into his chair, and drew another beside him. "You're all worn out tonight. Have you been overdoing things?"

"Nothing of the kind, Tony girl," and he slipped a hand over, and held, one of mine. "Besides," and he chuckled, "it was in a good cause—and only once a year, you know. But tell me—where have you been?"

"Oh, doing the same as on every December twenty-fourth, only a little more so. There seemed to be so much to talk about everywhere and—well, I stayed longer in places than I expected."

"Never mind, if you didn't get wet feet. Let me see. No. Fine! Now I'll order some coffee and we'll have a nice, comfy chat until the chimes—"

"You're a dear, Dad. But—I can't do more than drink one cup. Then I must be off again—"

"You must— What do you mean?"

"Dad, I'm really ashamed of myself. But you remember the Kellys—"

"You mean Bridget and little Johnny?" He nodded.

"Yes. And would you believe it, I all but forgot them?"

Then, as his eyes opened wide in thoughtful interest, I told him how I had recollected my lapse, my subway trip on my last nickel and what the thought of the Kelly tenement had recalled—my first Christmas Eve party, and Archer Huntington playing Santa Claus.

"That's strange, Tony," he interrupted, his brows coming down into a pucker. "It seems as if I've been thinking of good, old Archer most of the day myself. Sometimes I felt almost as if he were near me, particularly when I was with the children. Maybe, Tony girl, he was closer than I knew. We can't tell."

"Do you know, Dad, recalling Archer made me think of the money still hidden away somewhere in that old building. And I also thought—if only the Kellys had found it—what a glorious Christmas present it would be for them."

"It certainly would." He smiled "But that money is gone—at least until the wreckers tear down the house. Now let us let us get right down to the practical side of your predicament. I suppose you want some money to make good to little Johnny?"

"Yes, Dad, heaps of it. I'm going to give him the best Christmas he ever had. I'm going to try to atone for my forgetfulness, Dad—make good to the memory of Santa Claus Huntington for that first splendid Christmas he gave me."

Dad's hand went into his pocket and came out clutching a roll of bills which he thrust into my fingers.

"Make it the kind of a Christmas for Johnny you've been thinking about—then add a little more for Archer."

"Oh, Dad, I'll do it. And I'll thank you more tomorrow, when I have time. A big kiss and I'm off."

"But, Tony, it's a bad night. I think I'd better go with you and—"

"No, Dad. I'll dress warmly and—"

"But—"

"No 'buts,' Dad." I sat upon the arm of his chair, drew his head about until I looked full into his eyes, and brushed a strand of gray from his forehead. "I know you're game to go, if I say the word. But you're tired—far more than you realize.

"Besides, this is my job. I overlooked a real duty. Now I must make good. It won't take as long as you think. If you want to wait and doze and smoke here, we'll say, 'Merry Christmas' together, maybe with the chimes. I'll use the big car this time. No more being caught with but a nickel carfare. If you'd rather go to bed, I won't mind. For I want you fresh and rosy tomorrow, when you must be Santa Claus for me."

"All right, Tony. I'll telephone to Jim and Reddy to bring the machine around while you're getting ready. You'll need both of them with you to help carry the bundles and—well, if you should have a blowout on such a night—"

"Nothing like that is going to happen," I cried, giving him a final hug and kiss and dashing away. But he followed me into the hallway, shouting, "Good luck," over and over again as I hurried to my room, my precious roll of bills clutched tightly in my hand.

While changing to a heavier dress and directing Minnie to strap on a pair of arctics as a further protection against the drifts through which I must wade while making my purchases, I thought of Mrs. Kelly and the probably meager covering she possessed to shield her against weather such as the night had brought.

In a closet was a heavy coat, with cuffs and collar of fur, which I had bought for the housekeeper. She and Mrs. Kelly were about of a size. It would meet the emergency splendidly. The widow would have the coat and I would give the housekeeper money to get another.

It hung over one arm and my purse with the money for the Kellys' Christmas gifts was over the other when I again headed out into the snow.

"Where to, Miss?" queried Jim, while Reddy helped me into the car and tucked a big, warm robe about me.

"Hurry over to upper Broadway—some place where the shops are certain to be open. I must get a lot of toys and candy and—things. Then we're going over to Murray Hill. You know, where the Kelly family lives."

Another moment and we had turned the corner and were lurching ahead, horn rasping, our lights penetrating but little through the blanket of whirling flakes in front. But we reached the avenue safely. And the shops still were open, caring for last minute purchasers like myself.

With Reddy at my elbow, I plunged in and out of several, making my purchases quickly, while bill after bill disappeared from the roll of yellow and green backs. I bought toys and candy and more toys and fruit—until Reddy informed me the car was pretty well filled. But I only laughed. There must be room for a few more parcels. I had promised myself that Johnny's Christmas was to be a bumper one. And I was determined he should fare as splendidly as any boy in all New York.

My final errand was to a neighborhood department store, where the weary clerks already were preparing to close. "I am going to leave all choice to you," I said to a man behind the nearest counter. "I want a number of things for a five-year-old boy, of slight build and about so high-—two pairs of shoes, rubbers, two suits, an overcoat, a fur cap, gloves and a box of wool stockings. Don't show them to me, but give me the best. And please hurry."

I don't believe I ever was happier in my life; not even at my first Christmas party, as the car zig-zagged its way across town and down toward Murray Hill. Even Archer Huntington, if he were looking down upon me, must have smiled at my effort to follow in his footsteps. For, somehow, I seemed to feel that he was responsible for the joy of giving, which I always had known at Christmas time. When we finally drew up before the ramshackle old building which housed the Kellys, with only a lighted window here and there to relieve its dull front, I caught the echo of chimes from some nearby church, hushed and muffled by the storm till they sounded like some wayside angelus bells.

Christmas had come. It was the midnight hour when Santa Claus must start upon his all important journey.

I laughed happily as I stepped from the car, while Reddy closed the door behind me. "Merry Christmas, boys. Wait here until I come back. I want to make certain Johnny is asleep. Then we can take the gifts to his mother." I carried only the coat, which was to be my personal gift to Bridget Kelly.

As I entered the hallway I encountered the janitress, reaching aloft to turn the sputtering gas flame to a mere speck, the customary illumination for those of the tenements who returned home after midnight.

She pushed her spectacles closer to her eyes, then, "And can it be yourself, Miss Gregory? And on such a night and so late? I'll be certain 'tis the Kellys you came to see. But she isn't home."

"Why, she can't be working so late."

"No. But one of the neighbors down the block's been taken sick. She's gone to help. I'm lookin' in on Johnny while she's away. But he's asleep now. I just came from up there. The door's open if you'd care to go up."

"Thanks. I've some Christmas things for them. I'll just make certain Johnny's still asleep. Then I'll have them put in Mrs. Kelly's kitchen. You can tell her they're there when she returns."

"Bless you, Miss, they'll sure be appreciated this year. Bridget hasn't been able to work much lately and the doctors cost a lot o' money. I fear she couldn't get much for the laddie for Christmas and—"

"Yes?"

"Well, don't says as I said so, but I guess. they been a eatin' pretty poorly for the last week."

I drew another bill, a twenty, from my almost depleted roll, then went to the door and told Reddy to go to the store around the corner and get a big turkey and all the trimmings.

When I reached the fourth floor, where the Kellys lived, in the rear, I listened. No sound came from within. And but the tiniest chink of light showed beneath the second door, which I knew opened directly upon the kitchen and living room. Johnny slept there. For it kept him near the big stove, which supplied all the heat for the diminutive flat.

On tip-toe I moved to the other door, the one to the narrow inner hallway. I turned the knob gently, entered without sound and closed it behind me. The place was fearsomely still. But, as I listened. I caught the faint, regular breathing of a child. Johnny was asleep. I moved to the doorway of the kitchen. A lamp burned upon a table, placed so that its rays fell upon the boy's bed, probably to give him courage to remain alone while his mother was absent upon her errand of mercy.

Then my eyes wandered about and across the shadows, to the stove and the old mantel behind it. A lump came into my throat as I noted the little stocking hanging there. Johnny's stocking, waiting to be filled by Santa Claus.

Poor little laddie. And I had almost forgotten him. No Santa would come to the Kelly flat. But there would be gifts aplenty—more than Johnny possibly could have dreamed of possessing.

No need to wait for the return of Mrs. Kelly. Reddy and I would bring the gifts and leave them. Johnny was too sound asleep to awaken. And we would move quietly.

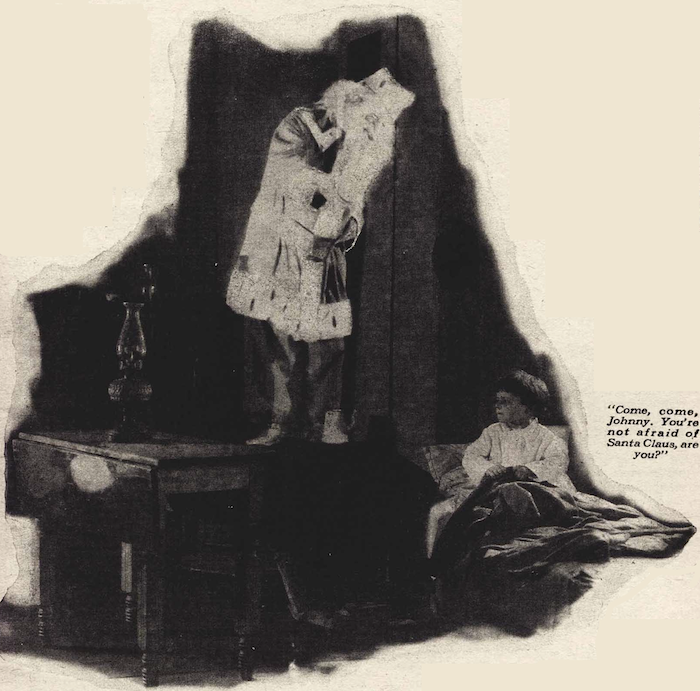

I was about to turn back into the hallway when suddenly, with a gasp of fright, Johnny sat straight up in bed and stared before him, toward the stove, with wide eyes, his mouth agape.

I turned and looked, where he was gazing. And my whole body went numb and I leaned against the casement, half dazed, at what I saw.

For, standing atop the stove—stood Santa Claus—as I had seen him pictured —thousands of times—smiling, eyes shining, a wide belt holding his fur trimmed jacket close to his fat, round stomach and high boots coming far up over his short legs. Only his pack of toys was missing.

But, as I gazed, as speechless as Johnny, the feeling of fear slipped from me. Then I noted that the figure appeared shadowy, in some indescribable way—unlike the body of a person one could reach out and touch.

And his features—somehow they appeared familiar. There was something about the look in his eyes, his jolly grin, his long, flowing white whiskers, which I seemed to remember.

"Merry Christmas, Johnny, Merry Christmas!" The voice seemed to crackle with good nature and merriment.

"Merry Chr—" Johnny's greeting died away in an awed whisper.

"Come, come Johnny. You're not afraid of Santa Claus, are you?"

"Come,come, Johnny. You're not afraid of Santa Claus, are you?"

"N-no, sir." The lad's tone was more confident.

"That's better. I see you expected me, and hung up your stocking here." His rolling chuckle brought a grin to the boy's face.

"Now, Johnny, tell me. Have you been a good boy all year?"

"I—I guess so. Mother says so."

"That's fine." Then he winked. "Mothers always know, don't they?"

Johnny nodded solemnly.

"And, since you've been a good boy, I suppose you expect a lot of presents?"

"No, sir. Not this year."

A momentary shadow flitted across the old fellow's face. He hopped from the stove, stepped to Johnny's bed, and leaned over familiarly, resting his elbows upon the footboard.

"Do you mean you don't expect presents because I haven't my pack with me?"

"No, sir. Not 'zactly. But—"

"Of course not. You wouldn't expect Santa Claus to show little boys what he's going to leave for them, now would you?"

Johnny hesitated, as if lost for words. Then, "I—I guess I don't know—quite—Mister. But Mother's been sick, a whole lot. And she said when there's sickness you don't leave much until they're well again—"

"Wait a minute, Johnny" The old fellow raised a hand that trembled, and he held it before his eyes. "Listen, my boy. Mothers are right—almost always. But—well, never mind. Now here's a secret, just between you and me. I'm going to surprise Mother this time. I'm going to make it a real Merry Christmas for you both."

"Oh, good!"

"Yes, Johnny. There's going to be toys for you, heaps of them—and new clothes and candy and a big dinner with turkey and red cranberry jelly and—"

"Gee!"

"And listen—stoop closer. There's going to be a new coat for Mother—a long, warm one, with a big fur collar and—a big surprise for you both."

The lad was astonished into complete silence.

"But, Johnny, Santa Claus can't leave things while little, boys are awake. You must close your eyes, tight, and go to sleep. Then all the fine presents will be left—"

"And we can have them in the morning?"

"You surely can. And if you're a good boy next year, there'll be more presents. Now good night and a Merry Christmas!"

With a flash like that of a darting shadow, the little man hopped to the stove, then to the mantel—and disappeared into nothingness.

But, as he disappeared, there came a crash—one which startled me and brought a cry from Johnny, crouching in his bed, his eyes wide, staring after his departed visitor. Then he dropped back upon his pillow, his tiny mouth held in a smile as his lids closed and he again drifted into slumberland.

However, the crash meant more to me than it had to the boy, too excited because of his talk with Santa Claus to pay more than passing heed to other things. Waiting only until I noted his regular breathing, I tip-toed to the stove. Beside it lay a little pile of glass, caused by a vase from the mantel having fallen and broken.

But it was the appearance of the mantel which caught and held me. A piece of the top, fully a foot in length, had dropped and was hanging. I stepped closer. The piece was held by a hinge, cunningly set into the wall. And the exposed top of the upright showed an opening. I plunged my hand into it—drew out a small tin box. This I carried nearer the light. It was unlocked. I raised the lid—exposing a heap of coins, mostly gold. In a flash the truth came to me. The hidden cache of treasure finally was exposed. Instantly I determined it should be added to the Christmas gifts of Bridget and Johnny.

And, as I turned away to go below and tell Reddy and Jim to bring the presents I had brought, I knew, beyond all question, that the Santa Claus I had seen was the phantom of Archer Huntington—that it was Archer Huntington's Christmas ghost who had touched the spring that had uncovered the long hidden treasure—to gladden the heart of little Johnny Kelly!