I remember vividly the conversation in Doctor Immanuel's library, because that evening was the beginning of my association with him, and the conversation was, so to say, the starting point of my own investigations.

There were five of us there, Dr. Phileas Immanuel, Doctor Maine, Paul Tarrant, the millionaire whose priceless art collections passed to the nation recently under the terms of his will, and another man whose name I have forgotten. We had been discussing the case of Helen Blythe, Mr. Tarrant's governess, who had been dismissed for stealing, after the court had passed a suspended sentence upon her by grace of a defense of kleptomania.

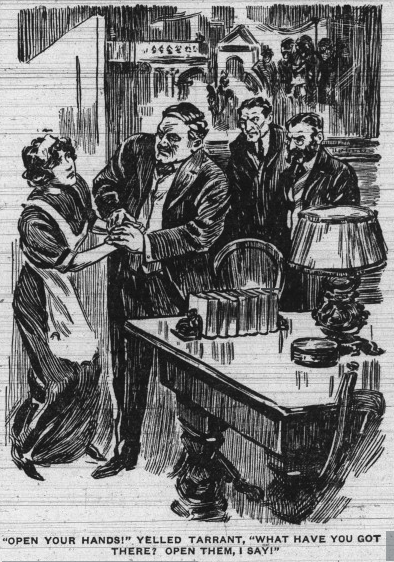

"Open your hands!" yelled Tarrant. "What have you got there? Open them, I say!"

"You say," said Doctor Maine, the eminent neurologist, "that you believe in reincarnation upon the analogy of the plant—the lilac plant, you used for an example. The lilac, as I understand you to say, flowers during some two weeks in the year and, having faded, reviews its earthly experiences in some paradise of dreamy somnolence until, in due season, the soul of the flower incarnates itself in another cluster of petals. So, you say, man comes to birth again after he has passed through the gates of death. That's not a bad simile, Immanuel, but that's not biology. How do you justify your belief biologically—or, let us say, by any laws of inductive reasoning?"

"You are, of course, acquainted with the researches of Freud?" asked the Greek doctor of Maine.

"Well, I should say so," the other responded. "A big man—one of the biggest in his line of today."

"How would you sum up his discoveries?" asked Doctor Immanuel.

Doctor Maine did not hesitate for an instant. "Freud's great work," he said, "has been the proof that our subconscious or dream life is continuous, that every dream accurately corresponds to some ungratified physical or mental need and is, one may say, its fulfilment. For instance, take the man who has always wanted, but never owned, a motor car. His dreams will show a more or less continuous experience—not of motoring, for they will be veiled under some symbol, but of flying, or aeroplaning, or holding the throttle of an engine. He may even be a fly on a wheel, or a swimmer clinging to an upturned boat in a whirlpool; but in some manner the dream life will reflect the waking wish."

"Precisely," answered Doctor Immanuel. "Well, now, let us carry the simile further. The condition after death represents to the full this dream life, magnified to the nth power. There, in that paradise of bliss, every ungratified wish that was ever experienced in life comes true—generally. But suppose that the impulse to rebirth cuts short the experiences of heaven prematurely. What then?"

He paused and, looking round at us, raised, his hand impressively. "Then, gentlemen, you have a soul reborn on earth which, instead of holding these past memories securely tucked away in the innermost recesses of its being, flowering as gifts of character and natural ability, is built upon shifting sands. The submerged consciousness of these unsatisfied needs of its past life haunts it and drives it to unlawful deeds. All our criminals, for example, are merely persons who failed to fulfill their destinies; and, in proof of my contention, are not all criminals—criminals by instinct, of course I mean, not the starving beggar who snatches a loaf—are they not all physically unstable, mentally unbalanced, and easy subjects for the hypnotist? Yes, my dear Maine, and I believe that when hypnotized they can be made to yield up these past memories."

The subject was changed soon afterward by Doctor Maine. Like many medicos of the old school, he held opinions rooted in the barren sands of materialism. Such theories as Immanuel's savored to him of the charlatan. But for the eminence of the Greek physician he would, I am sure, have broken forth in angry protest. He took his leave soon after, and the fifth man also departed, leaving Paul Tarrant, the doctor and myself alone.

"Now take the case of Helen Blythe," said Mr. Tarrant, when we had settled ourselves in our chairs again. "Do you suppose that you could prove your contention in her case?"

"I didn't read the account," answered Doctor Immanuel. "All reports of crime distress me exceedingly. When I think how futile it is to put these unhappy creatures in prison, instead of treating them medically, I become enraged at the world and disgusted with my own inability to convince penologists of their mistake. But tell me about her."

"Helen Blythe," said Mr. Tarrant, "is a well-bred, good-looking, modest young woman of, I should say, seven or eight and twenty. She came to me with excellent recommendations, to be a nursery governess for our children. Mrs. Tarrant took a great fancy to her and trusted her fully. Needless to say, neither of us was aware that Miss Blythe had been dismissed from a former situation for theft. As we discovered afterwards, she had stolen four valuable rings, which, in spite of the threat of prosecution, were never recovered. The girl claimed that she had forgotten where she had hidden them, but fully acknowledged her offense and repaid the value of them out of her savings. In spite of careful investigation of all the pawnshops in the city, however, the rings were never found.

"A few weeks after we had engaged Miss Blythe my wife began to miss valuables of hers. Rings seemed to be the young woman's penchant. An opal, a diamond and sapphire, and a magnificent emerald in a fifteenth century setting disappeared successively. We changed our servants without result. At last, by force of a constantly dwindling number of hypotheses, the suspicion came to rest upon Miss Blythe's shoulders.

"However, as Mrs. Tarrant locked away her valuables, nothing more was taken, and we should probably have kept the young woman in our employment but for what happened. The governess was a great student of antiquities; in fact, she had a knowledge of Hittite and Babylonian archaeology which astonished me and was the primary factor in the securing of her position. She had a half day's leave every week, and invariably spent it at the museum. She became a well-known figure there, for she always haunted the Assyrian room, in which, as you may know, are a number of engraved gems, of immeasurable value, brought from Babylonia by the expedition which I sent there for the purpose of excavating the mounds of Nineveh.

"Some ten days ago the watchman, who had somehow become suspicious of the young woman, discovered her with the half of a sacred amulet in her hand—a ring supposed to have been worn by the high priest of Marduk. As you may know, that half amulet is one of the most cherished possessions of the Assyrian department. The watchman arrested her and summoned the curator. When he came it was discovered that the half amulet still reposed in its place inside the case. The half which Helen Blythe held in her hand was mine—the other half, and willed by me to the museum. The young woman made no resistance, but suffered herself to be led away, as if in a comatose state. She was brought to my house. I identified the half of the charm, and the girl was placed under arrest, to be released under a suspended sentence yesterday."

"Where is the girl?" asked Doctor Immanuel.

"Why, doctor," said Mr. Tarrant, flushing, "I am ashamed to say that I have taken her back."

"Good!" ejaculated the doctor, puffing vigorously at his cigar. "But she will steal again."

"Indeed, no," answered the millionaire with conviction. "We had a very serious talk with her, Mrs. Tarrant and I. We told her that we felt, under the circumstances, which we had not fully understood, that we ought not to turn her adrift into the world. We thought that by the force of example, perhaps, we might cure her of her unfortunate propensity. And so she was re-engaged—not, of course, as governess, but as a sort of aid to my wife."

"And she was penitent?"

"Entirely so. She protested that she would conquer her weakness; she vowed never to touch jewelry again, or to look at it. She pleaded earnestly for our confidence, said it was only rings which she felt an irrestible temptation to take, and—"

"And she will steal again," said Doctor Immanuel.

"Well, doctor, you have a poor faith in human nature, considering your humanitarian profession," said the millionaire.

"I tell you, Mr. Tarrant, she will steal again," persisted the doctor. "You cannot eradicate the instincts derived from a former incarnation with kindness only. Doubtless she was a wealthy gem collector in Rome or Athens—or Alexandria, more likely—about the year 100 A. D."

Paul Tarrant smiled skeptically. "Will you tell me how you arrive at your date so exactly, doctor?" he asked.

"By the analogy of the lilac tree," replied Doctor Immanuel. "The lilac blooms for two weeks in every fifty-two—is that not so? Then we may say its sleeping life is twenty-six times as long as its life in physical form. Now, if we take the normal human life to be seventy years, each human item will reappear after an interval of about 1,820 years—shorter or longer according to the individual idiosyncrasy, but more or less upon time. Hannibal, for instance, whose discarnate life must have been peculiarly rich in memories, and therefore prolonged, was reborn as Napoleon after a little more than 2,000 years. Cicero reappeared as Gladstone after some 1,850 years; the fabulous Queen Semiramis after 2,000 years as Cleopatra, and after some 1,750 more as Catherine II of Russia. These mighty figures appear and reappear through history with the regularity of comets, and, like them, are recurrent phenomena which flash through a wondering world. Well, then, some 1,830 years ago your Helen Blythe was a gem collector or lapidary or something similar in the classic world, and it is the ungratifled desire for jewels which has made her a kleptomaniac today."

"Perhaps you would like to see her, doctor?" the millionaire suggested tolerantly. "I confess I am not convinced as to the truth of your theories, but I should immeasurably like to know just how the ancient Romans set their rings."

Doctor Immanuel accepted this seriously, and before we parted it was arranged that we two should visit Mr. Tarrant at his house after dinner on the following evening. So we separated, upon terms of the utmost goodwill, and both Mr. Tarrant and myself, I am sure, politely skeptical as to Doctor Immanuel's claims.

Doctor Immanuel was staying at my house at this time. He had been sent to America, where he had been educated, by the Greek government, as her most distinguished medical representative and publicist, to attend the International Congress of Penologists at Boston. But the first few days' sittings had so disheartened the doctor, convincing him that his own theories would never gain him a hearing, and would, in fact, seriously prejudice his country, that he had withdrawn from the congress and was making my home his headquarters during the period, occupied by some special researches, about whose nature he had not enlightened me.

On the following morning we received two letters from Mr. Tarrant, in which he apologized for his inability to ask us to dinner on account of the death of a near relative of Mrs. Tarrant, and reiterated his desire that we visit him that evening. Accordingly, about eight o'clock we found ourselves in his library and received a cordial greeting.

"Before we see Miss Blythe," said Mr. Tarrant, "perhaps you gentlemen would care to inspect my antiquities?"

We knew that such an invitation could not be refused without the possibility of seriously affronting the millionaire; furthermore we were both interested, in a limited way, in such matters. We did anticipate a lengthy and somewhat tedious round of the museum, but such proved not to be the case. Mr. Tarrant's collection consisted mainly of works of art of the middle ages; the Assyrian room was quite a small chamber at the back of the house, enclosed by concrete walls and approachable only by the door leading out of Mr. Tarrant's library. We entered. he switched on the electric lights, and we found ourselves looking up into the faces of bull-headed kings with wings, broken-faced goddesses, and colossi of black marble and granite. At one end of the room were a number of packing cases, forming a barrier across one-third of its length; down the center were the customary glass cases filled with gems, stones of all sorts, fragments of clay inscriptions, etc. We made the round slowly, Mr. Tarrant expatiating upon his trophies.

"And now," he said, "I must show you the gem of my collection in its literal sense—l mean the half amulet whose other part is in the museum. I don't keep it here," he added, smiling. "It is far too valuable, and my one experience of losing it has made me resolved to run no more risks. It is—" he paused and continued in a stage whisper which certainly carried as far as his natural voice—"under the Persian rug behind my desk, in a tiny piece of false parquet work in the floor. Simple, isn't it? Yet I am sure it is safer there than in any of these cases—or, for the matter of that, in a steel safe.

"First, let me tell you something about this treasure," he continued, waxing enthusiastic. "The amulet is supposed to have been made for the high priest of Marduk, at Babylon, According to the cuneiform inscription, it was kept by the priestess of Ishtar pending the completion of Marduk's colossal temple, and it is believed, since it was discovered in the ruins of the temple of Ishtar, that for some cause the priestess never delivered it. Perhaps it was hidden, perhaps the city was destroyed before the transfer could be made. At any rate, it was a most sacred object and, from the fact that it was made in two halves, it is certain that the highest value was placed upon it. But I am wearying you, gentlemen. Come into the library, and I will show it to you."

We passed into the library. Mr. Tarrant switched off the lights in the museum and, carefully closing and locking the door, switched on the library lights. As the room became illuminated we heard the door at the other end close softly. There was the swishing of skirts.

I was not prepared for what followed. With a yell the millionaire leaped across the room, burst open the door and reappeared, dragging with him the figure of a woman. Of course it was Miss Blythe. She stood staring at him, looking like a sleepwalker. Her hands were tightly closed.

"Open your hands!" yelled Mr. Tarrant "What have you got there? Open them, I say!"

But the frail woman seemed to have the strength of an athlete, for Mr. Warrant, powerful man though he was, could not open her hands. All the while she stood and stared at him, and she seemed to be utterly unconscious of our presence.

Doctor Immanuel walked over to her; he placed one hand on either shoulder and looked into her unwinking eyes.

"Helen," he said quietly, "open your hands!"

There was a moment of uncertainty, then the hard eyes closed and the hands opened obediently. With a cry of exultation, Mr. Tarrant pounced upon an object held in one of them—a massive ring containing an enormous engraved stone which looked like a sardonyx.

"Here it is! " he shouted. "Now, then, will one of you gentlemen go for an officer?"

Doctor Immanuel turned round and held up a finger in warning. "She doesn't hear you," he said quietly. "She is hypnotized."

"Nonsense!" exclaimed Mr. Tarrant, angrily. "How could you hypnotize her in that minute?"

"She has hypnotized herself," answered Doctor Immanuel. "She came to you in a hypnotic condition, and in her normal condition would be totally ignorant of what she has done. Helen," he added, softly, "you are in the hands of your friends. Go over and sit down on that sofa and sleep until I waken you."

The girl crossed the room obediently, walking just as a normal person would have done. She found the sofa and sat down; but all the while her eyes were closed. Mr. Tarrant stood by, still fuming.

"Have I your permission to proceed?" asked Doctor Immanuel. "I believe you invited us here for this very purpose. Mr. Tarrant."

"Oh, yes, by all means," Tarrant answered. "But you'll have to convince me before I allow her to leave this house except under police supervision."

"I hope to," answered the doctor. "But first let me assure you that this young woman could never be convicted of theft in any court. Ignorant as our police magistrates are, the understanding that there is such a thing as alternating personality has finally filtered into the public mind. If you will remember, you yourself told me that when Miss Blythe was arrested in the museum she suffered herself to be led away as though she were in a comatose condition."

"Yes—yes."

"The fact is, Mr. Tarrant, that Miss Blythe the governess is not in the least the same personality as Miss Blythe the kleptomaniac, and has no knowledge of her. She doubtless realizes that, when these periods of forgetfulness come on, she commits actions of which she has no waking knowledge, and it is the impossibility of explaining this to an incredulous world that has led her to suffer in silence rather than attempt to vindicate her reputation. Now, with your permission, I shall proceed."

Tarrant and I sat down. All this while Miss Blythe had not moved a muscle.

"Give me the amulet, please," said Doctor Immanuel, and Mr. Tarrant handed it to him with obvious reluctance. Had the situation been less dramatic it would have been amusing to see the intense gaze which the millionaire kept upon the gem.

"Helen," said Doctor Immanuel, holding up the gem before her, "can you read the inscription on this?"

"No," she answered in a voice which seemed disappointingly natural, "it is in Assyrian cuneiform, is it not?"

"Oh, yes, you can read it," said the doctor coaxingly. "You are not half asleep yet. Go to sleep completely, now."

He stroked her forehead caressingly, and when he held up the amulet and asked the question again, it was a totally different voice that answered him—a woman's voice, but harsh and nasal and strident.

"Why should I read it?" it asked protestingly.

"Read it!" said Doctor Immanuel. "No, read it in English"—for the voice had begun to talk in a sort of gibberish totally unlike any language that I had ever heard spoken, and bearing a distant resemblance to what I imagine Chinese must be.

"To the high priest of Marduk in Babylon," whined the voice. "Made for and donated by Asshur—Tiglath—Pileser, king in Nineveh—"

Paul Tarrant leaped out of his chair.

"That solves it," he shouted, and sank down again and stared round him like a man thoroughly bewildered.

"Solves what?" asked Doctor Immanuel quietly.

"That word Nineveh, doctor. The translations read 'King of Bel's slave,' and were utterly meaningless. If that is correct—it must be, but the stone was so rubbed none of us could decipher it—why, it places the date back to the thirty-fifth century, B. C., instead of the twenty-seventh. And that explains why the old cuneiform was used by the engraver."

"Who has this stone?" asked Doctor Immanuel, and we all gripped our seats more tightly at the snarling monosyllable "I!"

"Why did you not deliver it to the high priest of Marduk?" the doctor asked.

"I did. He would not receive it," shrilled the woman on the sofa. "Instead, he sent soldiers to arrest me. It is his. He does not know. He —"

Her voice ceased, her eyes were open, and she was clinging desperately round Doctor Immanuel's neck and deathly pale. She shuddered and quailed as though in intolerable fear; and she would have screamed but that she could not find her voice again. Then she collapsed, a dead weight, in the doctor's arms, and he placed her in a supine posture upon the sofa.

"Call your housekeeper and we will help carry her to her room," said Doctor Immanuel. "No,"—for Mr. Tarrant was protesting—"it will be all right now. The strain was too intense for her; the awakening too sudden, but she will sleep peacefully and, but for a little nausea tomorrow, she will be quite herself again. And she will have no recollection of what has occurred."

"I don't want to let the housekeeper know," Mr. Tarrant answered. "Help me, doctor, and we will take her upstairs. I'm glad my wife is not at home tonight," he added, grimly. "She mightn't approve of this."

But Mr. Tarrant took good care to secure and pocket the amulet before he took Miss Blythe's head and shoulders into his arms and led the way out of the library. I sat there for three or four minutes, wondering. I could not quite understand just what had occurred.

The two men came back arguing violently. Doctor Immanuel's voice rose high. and shrill above that of his friend.

"She told you the inscription on the stone and set you right some six centuries," he cried. "What other proof do you want, Tarrant?"

"Oh, well, it's all rubbish, you know," answered the millionaire. "Of course, now that I have the amulet, I don't want to have the girl sent to jail. But I can't keep a thief in my house—now can I, doctor?"

"She need not be a thief," Doctor Immanuel answered. "It all depends upon you."

"How so? Didn't you yourself tell me that she would steal again?"

"Yes. As long as she was looking for the opportunity to restore the lost amulet to the high priest."

"Well, I guess she'll have to go on looking for him,'' said Mr. Tarrant. "What do you want me to do—take her to Babylon and look for the incarnation of the old fellow among the desert Bedouin?"

"Why, my dear Tarrant, you don't suppose you'll find him there, do you?" the doctor asked quizzically. "More probably in this city. Do you suppose a man of that intelligence is condemned to be reborn as a camel herder? The civilization of Babylon passed on to Rome and thence to England and America, just as the Hindus became the Egyptians and the Greek republics, the republics of Florence, Genoa and Pisa and Venice in the middle ages."

"Now look here, Tarrant," he continued, as they sat down, "here is the situation as I size it up. Believe me or I not, as you please—it doesn't matter. Your Helen Blythe was once the priestess of Ishtar. It wasn't a position that called for any high intellect; it was a semi-servile position, in fact, and the priestess was chosen mainly for her appearance and birth. We may suppose that in her former birth she had merited her good fortune, by generous deeds, but, once the reward had been enjoyed, she sank down to the grade of governess again—or its equivalent in the ancient world. She had the care of this amulet. She was bound under the most sacrosanct of oaths to deliver it to the priest of Marduk. For some cause she failed to fulfill her task, and the omission so profoundly affected her that it lay like an incubus on her soul during her next incarnation. She stole rings, obsessed solely by the desire to discover the lost amulet again. At last she found it. She took it to the museum—still in her entranced condition—and was on the point of placing it with the other half when she was arrested, or, as she rather confusedly interpreted the occurrence when on the borderline between sleep and waking, 'the king sent, soldiers to arrest her'—probably the police and watchmen at the museum. Now, Tarrant, send the half amulet to the museum and you will find it perfectly safe to keep Miss Blythe in your house henceforward."

"Well, said Mr. Tarrant, "to be frank, I have intended to present it to the museum shortly, and after my experiences of the past few days I'll follow your advice. But as for keeping her in my employment—"

"Try it, Tarrant," pleaded Doctor Immanuel.

"Suppose she steals—"

"She won't steal any more, when once the amulet is in safekeeping."

Mr. Tarrant drummed his hands on his knees.

"Oh, all right, have your way," he said shortly. "But, by the way, Immanuel, do you mean to insinuate that Doctor Faust, our curator, is a reincarnatlon of the high priest of Marduk? He would be horrified to hear you say that. Why, he is a director of two Sunday schools and contributes liberally to foreign missions in—" He paused.

"Yes, where?" asked Doctor Immanuel.

"In Assyria and Mesopotamia," answered Mr. Tarrant sheepishly.

And Doctor Immanuel forebore to press his advantage home.

"But look here," said Mr. Tarrant, presently, "how does your 1820 year period work out, doctor? The amulet, according to our revised estimate, was made in the thirty-fifth century before Christ."

Doctor Immanuel began to estimate. "Our period takes us back to the year 100, does it not?" he asked. "The birth before that, then, would have been about 1750 B.C., probably in Egypt. Add 1820 years and we have the year 3570. Yes, there you are, Tarrant. And if you can discover the precise age of the amulet you will be able to estimate the exact age of your governess."

"It must have been a mighty strong influence to last over three incarnations, Doctor," said the millionaire irreverently. "Where do you suppose she spent the last two—and how?"

"Expiating her crime," Doctor Immanuel answered. "Doubtless as a thief and outcast—faugh, don't let us pursue that matter, Tarrant. She's won through all of that, poor girl. You're going to keep and help her, Tarrant, aren't you?"

And Tarrant promised.

Part of the series Phileas Immanuel, Tracer of Egos

Illustration from The Evening Republican Jan. 31, 1917. Source: Hoosier State Chronicles