My acquaintance with Dr. Phileas Immanuel had begun prosaically enough. The little Greek was in America as his government's representative to some international congress, I think of penologists, at Boston, and after he had withdrawn from it in disgust he made my house his headquarters while he engaged in some special research work. The acquaintance ripened so rapidly into friendship, and then into intimacy, that when the doctor invited me to accompany him to Europe, where he had some engagements to fulfill, I could not resist the opportunity. My practice was almost entirely hospital work, and fortunately I found no difficulty in obtaining a representative to fill my post during my absence.

So much to explain how we happened to be in England during the glorious summer of 1911. Immanuel found England to his liking, chiefly, I think, because medical men there extended a more kindly attention to his theories, although I fear he made few converts. Immanuel's claim that reincarnation would be found to solve most of the problems of abnormal psychic states could not be expected to find recruits in a century still dominated by Huxley and Haeckel and the great materialists. Nowhere, I fancy, can one find more stubborn, out and out doctrinaires than among medical men. But the doctor did not mind. He went blandly about his way, winning friends, disarming enemies, and, incidentally, making cures.

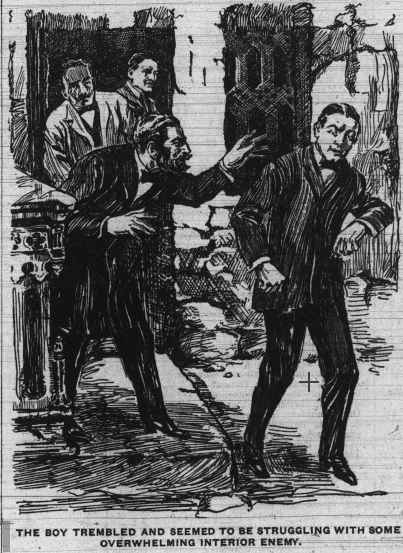

The boy trembled and seemed to be struggling with some overwhelming interior enemy.

When Sir John Carfax invited us to spend a week at his fine old mansion in Buckinghamshire we both accepted with considerable satisfaction. Sir John's place was one of the historic county seats of England. Originally a priory, it had been confiscated from the order by Henry VIII, and given to Francis Carfax, a shrewd lawyer of that age, for services rendered in connection with that monarch's marriage to Anne Boleyn. From him it had passed down to Sir John, in the direct line, but never through the immediate heir. This Sir John explained to us as he conveyed us from Great Marlow station in his automobile.

"I mentioned to you, Doctor Immanuel, that my son, my only child, is dangerously ill," he said. "Yes, he's dying, and I know it, doctor, and there is no power on earth can save him unless you—" He broke off. "I know you have accomplished wonderful cures," he continued. "I can't pretend to believe in what you believe, but—" Here he ended, for his tongue was running away with him, and the blunt country gentleman was no metaphysician or flatterer, either.

"But you are willing to stake your faith against your unbelief," said Doctor Immanuel cheerfully. "Good! I am no faith healer, Sir John; I believe even the most orthodox of my opponents have never accused me of any but orthodox methods of practice. My theories, you understand, are the base on which I stand to take action. But to believe—why, abuse me as much as you please, whether I succeed or fail."

I was sure no one could ever abuse the kindly little man as I saw him arguing excitedly with Sir John. As I have said, he disarmed all his enemies. But it was hard to ask a twentieth century English gentleman to accept reincarnation.

"If you can save him, doctor," continued our host, "I can only say that you will have my deepest gratitude. But I fear it is hopeless. He will be the last of the line, and his mother is dead. I shall never marry again."

"Why are you so despondent as to the possibility of a cure?" asked Immanuel.

Sir John looked at our faces searchingly. "You have never heard of the Carfax curse?" he asked. "Well—perhaps it is regarded as an amusing superstition even in England, among those who have heard of it. But among those who know it is anything but a jest. Doctor Immanuel, for nearly four hundred years the first-born son of the Carfaxes has died in childhood. Arthur is seventeen; he has outlived them all. But he, too, must go. I know it. It was prophesied by the last prior, Ignatius, as he strode out of the chapel after his last mass there."

"Those curses are potent things," said Immanuel. "So much I know. They do come true, by reason of the strong subconscious impression which they leave behind, to be transmitted from generation to generation. Of course the curse is nothing. But if a man begets a son, believing that he will never grow to manhood, and if he bases his life upon that theory—why, it generally comes true. But I interrupted you."

"The last prior, Ignatius, made this prophecy to Francis Carfax, my ancestor, somewhere about the year 1545," said Sir John Carfax. "That the priory should never descend from father to son through the first-born until the priors should come to Carfax, again and replace the altar cloth upon the altar."

"The altar cloth?"

"Yes, a famous relic, said to have been brought into England by Edward the Confessor, and reputedly of great sanctity. The priors are supposed to have taken it away with them. It was never found. But now, you see, if the prophecy has been fulfilled since 1545, what hope has Arthur?"

"What do the doctors say is the matter with him?"

Sir John threw up his hands with a gesture of helplessness. "The doctors!" he repeated. "Why—they know. They know that the hereditary curse has descended upon the boy. Six months ago he was taken sick with a wasting disease. There is nothing organically wrong with him; he is just wasting away. Day by day he grows weaker, and his death seems now to be a matter of a few weeks only. And the tragic thing is that he knows; he knows that he must die; and his only pleasure is in sitting before the dismantled altar in the old ruined chapel and dozing there. He has been afflicted with somnambulism since childhood, and whenever his attendant misses him from his bed, he knows where he will be found; before the altar, fast asleep, and talking to himself."

The automobile swung off the high road and into the grounds of a stately park, through whose vistas of leafy trees could be seen herds of fallow deer, peacefully browsing. The road swung to the right between two rows of ancient elms, and now we could see the square stone towers of Carfax, with the dismantled, ruined stone chapel upon a knoll a little to the right of it. The chauffeur and butler were waiting at the door; the former took the machine to the garage, while the latter respectfully received our baggage.

"How is Mr. Arthur?" asked Sir John.

"He seems to be better today, sir," the butler answered. "He was reading in the chapel a while ago. Here he comes now, sir."

A tall, slim, gracefully built young fellow was coming slowly across the lawn and, seeing us, he stopped shyly. His father called him.

"Come here, Arthur," he said. "Doctor Immanuel, this is my son about whom we were speaking." He introduced the boy to me also. "How do you feel today?' he asked, anxiously.

"Better, father," said the boy in an odd, emotionless tone. As he walked slowly into the house his father looked after him and then turned wistfully to us.

"He knows," he said. "And he doesn't seem to care. That is the tragedy of it. They all go like that. I remember my poor brother Walter—he died in the same way. And yet the doctors can find nothing wrong with him."

"Suppose I examine him at once and let you know the exact condition," said Immanuel cheerfully. "If we can't beat the curse together, with all the resources of modern science, I shall be greatly surprised. What treatment is he receiving?"

"The usual thing. Tonics, beef extracts, iron; the physicians have taken his blood count and call it pernicious anemia. But they don't say how it arose. And there is nothing organically wrong." The poor fellow seemed to cling to that one hope.

"There is a new solution of arsenic which is used very successfully for that," said Immanuel. "Then again there is hypnotism. I don't know which is better. Perhaps we will try both."

"Hypnotism!" exclaimed Sir John. "Is that the secret of your cures?"

"It is not exactly a secret," answered the doctor. "It is in very common use among physicians today and based upon known laws and not empirical."

"You mean that you can hypnotise him into thinking that he is well?"

"Yes. But any other fool could do that—only it wouldn't make him well. No, sir, the principle is simply this: The greater portion of the body functions automatically; that is to say without the consciousness of the brain. The stomach digests whether we ask it to or not, the heart beats, the liver secretes, and so on. Now take the spleen, which seems to be behaving badly in your son's case. We can't make our spleens come to order—no. But under hypnotism we can get deeper; we can get down to the consciousness of these half independent organs and tell them to be good. And then, sometimes under hypnotism we find ourselves on very interesting trails which I cannot persuade other physicians to follow up. We find other personalities at work, lost memories flourishing like fungus growth under smooth mosses and grasses—it is all very interesting, and some day the world will come to recognize it. But suppose we go in and I will examine the lad before dinner."

We were led to our apartments in a wing of the old place; two rooms side by side under low, sloping eaves from which rain drops were falling dismally upon the slate roof of the garage below. Our host waited outside while we washed off the grime of the journey.

"Ah, my dear Sir John, I know you will not rest until I have looked at the boy," said Immanuel cheerfully, intercepting him as he restlessly paced the long corridor. "Come, then. Where shall it be?" He was dangling his stethoscope from his finger and thumb.

"We'd better go into the library," answered our host, and led us to a comfortable room, furnished in red morocco, on the main floor. The furniture was of old oak, blackened with age and worm-eaten. Outside the sloping lawn ran up to the ivy-covered base of the chapel.

The boy came in presently and Sir John rose to go. I had hoped that I should be asked to remain and assist at the examination, but Immanuel did not offer to detain me. He was alone with him for half an hour and came out looking quite cheerful, one hand resting upon Arthur's shoulder.

"A very intelligent lad," he said, patting him upon the arm affectionately. "We've talked over lots of matters. But first let me tell you that he is as sound as a bell. Nothing wrong at all, and his blood has as many red corpuscles as yours or mine. Now, Arthur, you've heard my diagnosis. Do you think you can get well?"

"I think I could if I could stop dreaming," the lad answered, I saw his father shoot a swift glance at him.

"You haven't told anybody else about your dreams?" asked Immanuel.

"No, doctor. They wouldn't take any notice."

"What do you dream?"

"I don't remember, except that they leave me dreadfully unhappy and depressed and weak, and I always seem to be worse when I have dreamed."

"And then you wake and find yourself In the chapel?" said Immanuel suddenly.

The boy was taken by surprise; he looked at the other quickly. "Yes, sir," he murmured.

"You see, gentlemen, the dreams are the immediate cause of his illness," said the Greek. "Two hundred years ago we should have said that he was possessed. A hundred years ago we should have tried to beat the devil out of him. Fifty years ago we should have sent him to sea. But today for the first time in human history we can treat such cases intelligently. We can recall these unknown dreams to him."

"Under hypnotism?"

"Yes, and can cure the cause. Freud has shown the intimate connention between dream life and waking life. I have shown that there is often another connection; that in dreams we live again in dead, past lives, otherwise totally forgotten. That is the only difference, and it is one of theory, not of procedure. You can safely intrust your son's cure to me."

"I do so with all my heart, Immanuel," exclaimed Sir John, who had been completely captivated by the little doctor's graciousness of personality and manner.

"Then, my son, we'll hypnotise you this evening and find out what you have been dreaming about," said the doctor to the boy. "Now you had better go out into the fresh air for a while. What do you say to taking us over to the chapel?"

"An excellent suggestion!" said Sir John. "Get your hat, Arthur; it is cool today." When the boy had gone he turned to the doctor. "Do you tell your patients what you are going to do?" he asked.

"Generally—yes. Confidence begets confidence. Besides, it is difficult to hypnotise anyone against his will, except in certain abnormal conditions. And your son is as normal and healthy as you could wish. It is his dreams that are killing him," he continued. "There is the key that shall unlock the secret. He has been a sleepwalker since childhood?"

"Since he was a baby. But never so badly as during the last year."

"And you trace his illness from the time this trouble began to develop?"

"Yes."

"He always goes to the chapel?"

"Invariably."

"Then—" began the doctor, but checked himself. He fell into a brown study; he seemed to have made an important deduction. He was still pondering when Arthur returned with his hat and the chapel key, and we left the house together.

The old ruin rose like some dismantled hulk out of the long, daisy-studded grass. Sir John Carfax turned the huge iron key in the old rusted lock of the oaken door and admitted us into a chilly stone chamber, bare of seats—though the grooves worn by their iron feet in the stone floor during centuries still remained. One part of the roof had fallen, letting in the light and affording a pleasing canopy of sky. Moisture dripped from the moss-grown walls upon the flags, between which clusters of weak grass sprouted. The ground before the wooden altar, the only part of the original furnishings which remained, was hollowed by the feet of bygone priors. Behind it was the remnant of a stone recess in which the sacred vessels and garments had been kept; but the doors had long since gone and only the blackened bronze hinges remained, a tribute to the death-defying skill of the old artist who had fashioned them.

"Here is Arthur's favorite seat—when he comes to it in his sleep," whispered Sir John, pointing to a stone seat in the rear of the chapel, immediately beneath the vacant window frame. "There he sits, or else paces the floor, following the tracks of the priors along this groove. I have watched him and seen him kneel," he continued. "One might almost think he was one of the old priors reborn on earth."

"Ah! You believe in rebirth, then?" asked Doctor Immanuel.

The other looked confused. "It was just a simile," he said.

"Say rather an instinctive recognition of what your memory tells you," Immanuel answered. "Well, we have seen it. Let us return."

"I thought," suggested Sir John, "that you might want to hypnotise him here."

"That," answered Immanuel, "would be fatal, for it would begin the procedure by placing a suggestion in his mind and so inhibit the developments which, if they are to occur, must occur of their own volition. No; in the library this evening."

Tumble-down though the priory was, the part in use was admirably furnished and adequately maintained. We four sat down to a semi-feudal dinner in state, while the butler poured the wine and the footmen carried in the heavy dishes with their silver covers and set them before Sir John for the carving. And a more excellent meal I never ate. When it was over we adjourned to the library and smoked some of our host's choice cigars.

"Now, Arthur," said Immanuel, throwing away the fragrant stump of his perfecto, "if you are ready we will begin. You have never been hypnotised before?"

"No, sir; but I have read about it and I believe in it."

"It is not necessary to believe in it, my boy," answered the doctor. "There is nothing empirical about the process; it is in daily use in all the large hospitals of the world. It simply consists in putting the upper strata of the personality to sleep by some mechanical method. I use a little instrument of my own devising, which answers every purpose. Now compose yourself comfortably in your chair and make your mind a blank, so far as possible."

He drew from his pocket a little instrument of silver—a sort of egg-timer with a revolving center, and attached it to a tiny pocket battery. Immediately the middle part began to gyrate at a rapid pace. It was dazzling to look at.

"Watch this" said Immanuel. "Now, see it revolve. There are between four and five hundred revolutions a minute. Yes, blink your eyes as much as you like, but don't turn them away. Sir John, will you lower the lamp a trifle?"

"Watch closely," continued the physician in a low and very soothing tone. "Now—you perceive that your eyes are becoming tired, and yet the strain is pleasant. You could not turn your eyes away now if you tried. Your consciousness is growing clearer, but is concentrated on this. You cannot think of anything but this. See how brightly it spins. Now you may close your eyes. You cannot open them."

The boy's eyes closed.

"You are not asleep," continued the doctor, "but you are in a sleepy condition. You must not go to sleep, but you will go down to where sleep is. What did you dream about last night?"

He shut off the battery and disconnected the instrument, replacing both in his pockets, and moved over to the boy and placed his hand gently upon his forehead.

"You dreamed about the chapel," he continued, "but you must try to remember. Why did you go to the chapel?"

"I went to find—"

"To find something that you have always wanted to find?" asked Doctor Immanuel.

"Yes."

"You have always been greatly distressed because you could not find it. If you could find it your troubles would be ended?"

"Yes."

"Describe it."

"It is a dish rag."

"No, it is not a dish rag. Try harder. You think it is a dish rag because it is white and coarsely woven. What is it?"

"It is a table-cloth."

"No, it is not a table-cloth. That is a better guess, but although it looks like a table-cloth it is not quite the same. Do you know where it is?"

"It is in the chapel."

"Tell me where."

"I don't know."

"O, yes, you know, but you have forgotten. You must remember; come, take us to the chapel and find it. You can open your eyes. But you will still be asleep, remember. You must not wake up."

The boy's eyes opened, but stared vacantly into the air. Apart from this he might have been in his normal condition. Sir John hurried toward him, but the doctor interposed.

"No, do not touch him," he said. "He sees nothing, but neither does one in sleep. Yet he will not hurt himself."

Arthur led us out of the library and along the passage, moving as surely as we ourselves. Doctor Immanuel unbarred the great doors and we all emerged into the star-lit night and passed over the lawn toward the chapel. The door had been left unlocked. Inside the darkness was not profound, but still none of us moved as surely as Arthur Carfax.

He walked more slowly, now, and a little uncertainly, passed the altar and stopped before his seat beneath the window frame. There he sat down and his hands fell to his sides. Doctor Immanuel took his seat upon the bench beside him, and we stood by.

"Now you must sleep more deeply." said the doctor, stroking the boy's forehead. "Sleep, sleep—and remember."

Arthur Carfax sprang to his feet and began pacing the grooves worn in the flags by the feet of the old priors. He paced slowly at first, then faster, then feverishly. As our eyes grew accustomed to the light we could see that his features were. slowly assuming an extraordinary change. The boyish look had disappeared and was succeeded by the look of a man—a man, too, in a condition of almost uncontrollable excitement or anger. We were appalled by this transformation.

"Find it!" hissed the doctor in the boy's ear, as he paused and turned, as if irresolutely, toward the altar. "You know where it is," he added, "for you hid it yourself."

The boy trembled and seemed to be struggling with some overwhelming interior enemy. Every muscle in his body was apparently convulsed.

"You won't wake up," cried the doctor in agitation. "You can't wake up. If you do you will have to begin all over again. You have sought it for seventeen years. Sleep! Sleep! Sleep! Find it!"

Suddenly Arthur Carfax darted toward the recess in the wall where the priests' vessels had been stored. He went down upon his knees and, without hesitation, began scraping away the dirt that had accumulated between the flags. We drew near and watched him. The boy scraped as though he held a trowel, and he ignored entirely the drops of blood that began to ooze from his finger tips.

"No, leave him," said Immanuel, to his father. "You must not interfere. Look! He has found it!"

Under the earth a paving stone had been disclosed, smaller than the rest and set slightly awry. Arthur began hammering with his fists upon one end. The stone suddenly swung back, disclosing a little chamber about as large as a cedar chest. And there was cedar there, for we could smell its fragrance. Even after three centuries the odor lasted.

Arthur pushed in his arm and pulled up a tarred package, apparently of some coarse linen fabric. The fibers came apart in his hands. He tore them and thrust them from him. Then underneath was disclosed a yellowed piece of fine linen, a square finely embroidered. The boy held it up, shook it out, and ran back to the altar, on which he deposited it

"The lost altar cloth!" shouted Sir John.

"Hush!" pleaded Immanuel.

The boy stood there quite calmly now. All trace of anger was gone from his features, which had assumed a nobility, a benignance which thrilled us. We drew nearer. He raised his arms in silence, as though pronouncing a blessing on us and on the old chapel. For a full half minute he stood thus, immovable; then his arms fell to his side and he tumbled into the doctor's arms.

"He's dead!" cried Sir John in anguish, as he sprang forward.

"Dead tired," answered Immanuel. "He will sleep like a top for the next twelve hours and after that he will remember nothing. But there will be no more dreams. Come, help me carry him in."

Sir John Carfax was a sorely puzzled man that night as we three sat talking in his library well into the small hours. Politeness struggled with skepticism, and yet skepticism itself was fighting hard with conviction.

"You say my son Arthur was once on earth as the Prior Ignatius?" he asked dubiously.

"Last on earth," corrected Immanuel. "He has been here a good many times before. But unless Ignatius managed to get a message through by him —which is a spiritualistic supposition—your son was actually Ignatius."

"And Ignatius lived in the sixteenth century," I interposed. "Did you not tell me once, doctor, that rebirth seldom or never occurred before the lapse of something like eighteen hundred years?"

"Yes. But we are now dealing with abnormal cases. I conceive that there is nothing to hinder a personality from returning earlier if it chooses, just as there is nothing to prevent a healthy man from cutting short his life by suicide. Indeed there are recorded cases of Burmese children who remember their prior existence as English army officers fifty years before." Somewhat related: Dr. Ian Stevenson was a researcher who studied evidence of reincarnation and children's past life memories. In 1977, he published the case of a Burmese girl who claimed to be the reincarnation of a World War II Japanese soldier, presumably a member of the Japanese occupying forces. You can find the paper here.

"Then the Prior Ignatius committed spiritual suicide?" I asked.

"Something like that. He voluntarily cut short his bliss in Paradise in order to atone for his crime."

"The curse?" asked Sir John.

"Yes. And the only way in which to stop it was to fulfill it per se by discovering the altar cloth."

"It's very odd," said our host thoughtfully. "But if you saved my son's life—"

"I haven't a doubt that he will live to a ripe old age with such a constitution as I discovered this morning."

"I have much to thank you for," said Sir John, and there were tears in his eyes. "I thank you with all my heart. And I will try to believe."

"Don't strain your conscience, Sir John," answered the little doctor cheerily. ‘‘lt doesn't matter, because—some day you'll know."

Part of the series Phileas Immanuel, Tracer of Egos

Illustration from The Evening Republican Feb. 21, 1917. Source: Hoosier State Chronicles