What terrible influence could cause the spirit of a demon to lodge in the heart of an innocent child?

"THE soul that builds itself a habitation and then refuses to dwell in it generally has some good reasons of its own. It is those reasons that we are seeking."

Doctor Martinus spoke these words in the little back study of his dingy brownstone house in the Seventies, New York City. His head was held high, the thin brown beard projecting aggressively, the pale blue eyes fixed half anxiously, half-quizzically, upon mine.

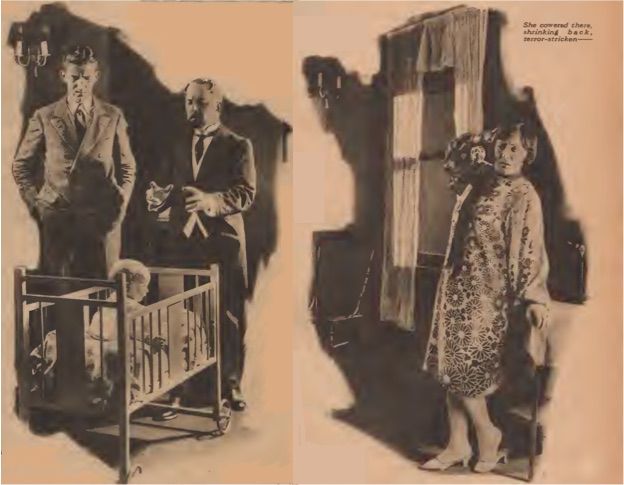

She cowered there, shrinking back, terror-stricken——

I had first come into contact with him when, as a newspaper reporter, I was sent to report—and incidentally to ridicule—certain phenomena alleged to be produced by a woman medium whom he was then sponsoring. These phenomena were inexplicable to me, and to the other newspaper men present; but, unlike them, I refused to pre-judge the case in accordance with what was expected of me. The result was a quarrel with the Editor, and my resignation from the paper. Subsequently, after a visit of curiosity that I paid Doctor Martinus, he offered me the post of secretary.

A Dutchman by birth, with small private means, he was engaged at the time in investigating a certain branch of psychic phenomena which required the services of a literary assistant. As a result of the reputation he had acquired, he was occasionally called upon to solve certain of those phenomena which persist in cropping up, even in these days, to disconcert materialistic theories.

"Branscombe," he would say to me, "sooner than strain my imagination by postulating a universal conspiracy among mediums of every nation to deceive the inquirer into believing in a post-mortem state, I would swallow the ten thousand witches that danced upon the point of Albertus Magnus' needle."

This remark was called forth by my suggestion that there was nothing mysterious about the case we were considering.

"After all," I asked, "what have we except an imbecile child, and

anxious parents who have perhaps imagined more than the facts warrant?

As for the dead woman's curse well, may that not have worked upon the

mother's mind and so have affected the child's mentality?"

"BRANSCOMBE, if you knew—if you only could know the thirst for

experiences of a soul rushing to incarnation, you would see the

fallacy of your suggestion. Life—the one great desire of all souls

whose cycle has brought them back to earth! Life—which fills every void

on land or sea, or in the air! And you suggest that the soul which built the body of that imbecile child is kept from occupying it because a vicious woman cursed the mother!

"No, Branscombe! Given the normal, healthy brain that the Adrian child possesses, it would require something more potent than the mother's imagination for that brain to be left soulless. You are acquainted with the facts?" He continued, turning upon me full-face, and looking me straight in the eye—a habit he followed frequently, and at unexpected moments.

"Not altogether," I said. "The mother seemed incoherent, and—"

"I should have taken you to Yonkers with me on that first visit of mine, but I was anxious to have you work out those data on prevoyance. Well, here it is on the card. The father, Richard Adrian, is branch manager of a life insurance office, a prosaic enough occupation. Presumably he receives a fair salary, and owns his own home at Number 100 Clinton Avenue, Yonkers. From there he commutes to the city daily. The wife is a charming and intelligent woman. They have been married for ten years. In spite of their intense longing for a child, they never had been blessed with one until eighteen months ago, when a healthy boy was born.

"Both parents adored little Robert," Doctor Martinus went on. "It was not until he was nearly a year old that they began to suspect there was anything wrong with his mentality. And the mother insists that the child was normal until a certain date. She can fix that date very clearly in her mind. And by the way, little Robert is not an imbecile, as you suppose, Branscombe."

"What, then?" I asked.

He went on more earnestly: "Branscombe, there is no doubt that this Adrian child has brought into this world a great deal more than the normal outfit with which the new-born human being is usually equipped. You know I base my theory of rebirth principally upon the fact that every human being comes into the world equipped with a set of tendencies and instincts that they have acquired in some former phase of existence. How otherwise can we explain the fact that a Bach, a Shelley, appears in a commonplace family, a Rachel is born into the home of a small trader, a Shakespeare in the family of a small town haberdasher?

"But, under normal circumstances," the Doctor continued, "all these tendencies are so wrought into the physical structure of the child that they appear only as unconscious instincts, and for the most part, after maturity—in other words, after the soul has finished building its house and is ready to resume its activities. In the case of this child there is evidence of a rather horrible purpose, as if incarnation had been devoted to one special end and plan.

"I shall not go into these details. You shall see and form your own opinion tomorrow night when we go to Yonkers to make our first attempt to unravel this psychic mystery. But the date from which Mrs. Adrian reckons the first appearance of these traits in the child is the anniversary of her sister's death."

"I did not quite gather the details of the curse that the sister placed upon the mother," I said to Martinus.

"The sister was several years older than Mrs. Adrian. She was a morbid, imaginative, and embittered old maid. Years ago she conceived the idea that Adrian would have married her, and that her sister had stolen him from her. She cursed Mrs. Adrian on her death-bed, a time when all the powers of the soul are capable of peculiar concentration. She predicted that if Mrs. Adrian ever had a child, it would be an imbecile, and would be the greatest misery to both its parents that they would ever experience throughout their lives."

I had seen enough of Doctor Martinus' work and methods to be prepared

for some extraordinary experiences at Yonkers, but the habit of

scepticism was so ingrained in me that I persisted in attempting to

apply the current methods of psycho-physical diagnosis to this

case. Certainly the surroundings were not of the kind commonly

associated with the super-normal. The Adrians had a pretty, commonplace, little house, surrounded with a low privet hedge; it had two rooms and a kitchen below, four bedrooms above. The furniture was of the usual instalment-house type—a hire-purchase piano, with "The Rosary" and "Danny Boy" on top, a radio set, and a potted fern upon a mahogany-finished stand in the front window.

WE arrived just after dark. Mrs. Adrian came to the door, a dish-towel in her hand, unfastening her apron with the other. She looked at us nervously, and I observed how worn and haggard she appeared—far more so than on the day when she came to Martinus' house.

"Please come in, Doctor Martinus," she began, not very cordially.

"Allow me to present Mr. Branscombe, my secretary," said the Doctor, for Mrs. Adrian was looking at me in a questioning mannter.

She bowed rather frigidly and, with what appeared to me to be hesitation, conducted us into the living- room. Here Adrian, a man of about thirty-seven or eight, was standing beside a chair, on which lay the evening newspaper. If Mrs. Adrian appeared haggard, Adrian himself seemed nervous almost to the point of insanity. His eyes were never still, and he started violently as Martinus tripped over the frayed edge of the Wilton rug.

"This is my busband," said Mrs. Adrian. "Richard, let me make you acquainted with Doctor Martinus. And Mister—Mister——"

"Branscombe," I interpolated. She had forgotten my name already.

"DOCTOR MARTINUS, I--I didn't know my wife went to consult you," began

Adrian hurriedly. "This is all—well, it wasn't with my approval. I'm a practical man, and I don't believe in such things. They're all imagination. There's

nothing the matter with Bobby, except that he's—well, he's——"

Martinus remained silent, his pale blue eyes fixed upon Adrian's. He had all the aspect of the practitioner listening to a refractory patient and at the same time observing him closely.

"How long have you suffered from this insomnia, Mr. Adrian?" he asked, ignoring our host's remarks.

"I—why—did you tell him we suffered from insomnia?" Adrian queried, scowling at his wife.

"Please don't resent the question," and Martinus smiled blandly. "To the professional man the symptoms are unmistakable. If it were only insomnia—well, there's an easy remedy for that."

"What do you mean?" Adrian asked.

"It looks as if they've set a trap for you—and caught you, Mr. Adrian. Both of you," the Doctor added, turning slightly toward the woman.

"They? A trap? Who? What trap?" Adrian almost shouted.

Martinus laid a hand upon his arm. "My dear fellow, how do they trap bears and other animals? By setting a trap along their runways, don't they? Similarly, when you pass into sleep, you leave your waking consciousness along a certain well-mapped route that you've always followed, thinking it is the only road. Well, they've put their trap there, and they catch you in it every night, and—"

He broke off. "You must learn that there are other roads, my dear fellow. Don't be like the frog that bit eight times in succession at the same piece of red flannel with a hook in it, before it learned it was not a fly. Come, let me see that boy of yours."

I expected an outburst of fury on Adrian's part. Instead, after a moment's hesitation, he subsided with a shrug of his shoulders. "Take these gentlemen up, Thyra," he said. "I guess it won't do any harm. Things couldn't be worse."

I had no idea what little Bobby Adrian would look like. I was afraid of seeing something grotesque or horrible. He was a boy eighteen months old, asleep in a crib in a very ordinary bedroom, close to the double bed in which his parents slept.

A pretty child he was, with flaxen hair and the silky skin of infancy, asleep with one hand underneath the face. The only thing amiss with him was that he appeared to be too fat, too red-blooded, for such a baby.

I like fat babies, but it was clear, even to my unskilled eyes, that there was something amiss with this one. The blood ran so red beneath the almost transparent skin, the lips were so scarlet. The child at once attracted and repelled me.

But the transformation in Mrs. Adrian's face as she bent over the crib had in it something of infinite pathos. Gone was the anxious, harassed look that I had noted downstairs; in place of it was the touching solicitude of the mother, that infinite yearning toward the child that makes a mother's devotion one of the finest things on earth.

As she leaned over the crib the little boy opened his eyes and smiled at her.

Mrs. Adrian looked up at Martinus, tears trembling on her own lashes. "He's always like this, so—so different when he first wakes up," she whispered.

"Yes," said Martinus softly. "They can't trap him—where he goes. 'In heaven their angels do constantly behold——'"

Suddenly, in an instant, the expression on little Bobby Adrian's face

was changed. In place of it appeared a cunning smile, a leer that

seemed to convey some dreadful knowledge. Then, as if seized with a

convulsive spasm, he jerked himself upright in his crib, screwed up

his face at his mother, and struck at her.

HE mouthed, grimaced, and then watched the result, his eyes following

Mrs. Adrian as she stepped quickly back to the far side of the room.

She cowered there, shrinking back, terror stricken—could a demon take

possession of an innocent baby?

At the same moment Richard Adrian appeared in the doorway. He had seen the incident, and now strode forward and confronted Martinus. "You see, he's always like that!" he exclaimed. "He hates his mother. Sometines I wish he was dead. He's possessed, if ever a child was."

"Yes, he's possessed," answered Martinus, "but so are we all possessed. Every time we let our passions ride us. The veil is very thin. ..."

He broke off and, bending over the crib, grasped the child by the arms, staring intently into its face. It stared back at him with leering impudence.

"Go back," said Martinus quietly. "This is not your time. Go to sleep now."

Gradually, as I watched, I saw a film seem to pass over the eyes. The look of intense hate that Bobby still directed toward his mother was succeeded by one of mere fatigue. Slowly the eyes closed. Martinus made a few passes over the face. Little Bobby slept.

Mrs. Adrian came forward. "What is it?" she whispered. "What is this evil spirit that seems to possess him? Is it—is it her?"

"That we shall find out in due course," answered Martinus. "With your permission, I shall bring another assistant here with me at an early date—Mrs. Sampson, a materializing medium who——"

"You mean that faker who was exposed by the New York newspapers?" asked Adrian hotly. "I won't have her in my house. I'd rather—I'd rather have things go on as they are than have any such exhibitions here. My child is sacred to me. I don't believe in such nonsense, anyway. Besides, if there is any occult world, we are not supposed to tamper with it."

"I can guarantee that Mrs. Sampson is no faker, as you term her, but a most respectable woman," answered Martinus, "However, just as you say."

Mrs. Adrian drew her husband aside and seemed to be pleading with him in low tones. Reluctantly he turned toward Martinus.

"Well, bring her along," he said. "Of course, you understand, if any harm comes of this—"

"No, no!" exclaimed Mrs. Adrian vehemently. "Do help us, Doctor. My husband is so distracted he doesn't know what he is saying."

"But that is too horrible for words!" I said to Martinus later. "You mean that the old legends of vampires are true? ... But the Adrian child cannot get out of its crib!" I exclaimed, as if I had penetrated his defenses.

"My dear Branscombe, you misunderstand the theory upon which that legend, as you call it, was built. The vampire never drew its sustenance from its victim in living form. On the contrary, he was invariably found at home in bed."

"You mean it materializes a phantom to perform its horrible work? But how can a phantom perform a physical act?"

"If you will look up your Homer, answered Martinus, "you will see that when Ulysses went down into Hades to consult the spirits, he had first to pour blood of oxen into a trench for them to feed on. The blood is the life, as the Bible tells us, and essential to a complete materialization. Even in the séance-room the medium often is forced to submit to a partial disintegration of the physical tissue in order to build up the body of the materializing entity."

"But a child—a baby like that!" I exclaimed.

"Branscombe," said Martinus solemnly, "a baby like that is quite a

satisfactory agent for the entity that is making use of it in the

fulfillment of its designs. Remember, the child itself is guiltless.

And remember what I was saying the other day, that the impulse toward

incarnation on the part of the dead who have completed the cycle of

discarnate life, or who are attached to earth by any strong emotion—this impulse is so intense that they will make use of anything, even the body of an animal.... But here is Mrs. Sampson, coming in at the door."

MRS. SAMPSON was the wife of a small contractor, living in the

Bronx. She had two grown daughters, and was, to all appearance, the

type of stout, motherly woman who might be expected to live in such

circumstances and surroundings. I had seen her before—she was, in

fact, the medium whom I had refused to "expose," and on whose account

I had severed my connection with my newspaper.

I had seen her perform certain inexplicable phenomena while in a state of trance. Judge my astonishment, therefore, when she began:

"Now, Doctor, you've been very kind to me, and you certainly helped my Margie when the doctors wanted to put her away, and she's engaged to marry a fine gentleman now, and I'll never cease to be grateful to you. And that's why I came. But you know Joe never liked me to take part in them conjuring tricks of yours, and he says there ain't going to be no more of it."

"Come, Mrs. Sampson, you won't turn me down when I need your help so badly," said Martinus, with a wheedling manner that sat so strangely on him could hardly keep from laughing.

"Where is it this time, Doctor?"

"In Yonkers," he answered. "Just some friends of mine who've got a boy who's a little out of his head. I've promised to help them, and I'm counting on you."

The woman pursed her lips. "You know, Doctor, this gets me in bad with the neighbors, and Margie being engaged now—no, I can't do it. Besides, it takes it all out of me, and I've never found out what you do while I'm asleep. I don't like it, Doctor, making an exhibition of myself before people that way. Besides, supposing the police was to raid the house? They fined a fortune-teller fifty dollars only last week for pretending to tell the future."

"Ah, but I really do tell the future," answered the Doctor. "Let me see your hand."

He took Mrs. Sampson's thick palm in his, examining it intently. "What's this?" he asked. "Money? Why, my dear lady, do you know you're going to be richer than you ever dreamed of being, inside of a year?"

"Why, that must be Uncle Jim!" exclaimed Mrs. Sampson, in agitation. "He said he'd leave me something, but it's years since I seen him, and I guessed he'd sort of forgotten me. Do you really see money in my hand?"

"I see more than that, Mrs. Sampson," responded Martinus gravely. "What's this? Why, Mrs. Sampson, inside of a year you are going to have—no, surely that can't be so—and yet the palm can't lie. I see the cutest little fairy of a child——"

Mrs. Sampson blushed and bridled. "Why, Doctor, don't you see? That's Margie's baby!" she said, all in a flutter.

Martinus released her hand. "True, of course!" he exclaimed. "Why didn't I think of that before? Well, Mrs. Sampson, I'm sorry you can't come, but guess I can find somebody _"

"Now don't you go so fast," said the woman. "I don't really see how I mightn't be willing to oblige, seeing what you done for Margie, and it being a private house..."

Five minutes later she left, with the understanding that she was to come to us two days later, on the evening arranged for the séance. Martinus was in high good humor when he came back, after closing the door on her.

"You certainly know how to handle women of that type," I suggested.

He smiled, and shrugged his shoulders. "She's always that way at first," he answered. "It gives her an increased sense of her own importance. She hasn't the least conception of what happens while she's in a trance, and doesn't dream she's one of the best materializing mediums in the country."

"Suppose Uncle Jim doesn't leave her that money," I suggested.

"I didn't say it was Uncle Jim," answered the Doctor. "Though, as a matter of fact, she predicted herself, while in trance, that she would receive it, and she seems to have the genuine faculty of prevoyance. But, anyway," and laughed, "we've helped the cause along."

MARTINUS told me his plans on our way up to Yonkers, Mrs. Sampson, on

my other side, absorbed in Evening Graphic.

"We are going to lay a trap, or, rather, bait a trap, for this entity," he said, "exactly as it baits a trap for poor Adrian and his wife when they cross in sleep to the other side, where it has its haunt. You know the proverbial stupidity of the ghost, according to German folk-lore. Whether or not it sees through our motives, it will be unable to resist the lure, simply because of what I have often spoken of—-the irresistible impulse toward incarnation.

"In plainer words, we shall endeavor to cause this thing, whatever it is, to leave the child and enter the body of good Mrs. Sampson, because she has the faculty of enabling it to attain the one thing it longs for more than any other—material life.

"Material life?" I echoed.

"Material life—for a few seconds only, but, nevertheless, while it lasts, intensely real and intensely gratifying."

"But do you mean to assert that the materialized spirit actually consists of flesh and blood?" I asked.

"Why not, my dear Branscombe? Nature has provided more than one method of reproduction among the orders—three, at least, corresponding to the three kingdoms; what is there improbable in the suggestion that she can make use of a fourth? And materialization through ectoplasmic secretion is, after all, extremely similar to the reproduction of a tree or plant by budding.

"If you will read Sir William Crookes' account of his investigations in this subject,

Sir William Crookes (1832-1919) was an English chemist and physicist. He is credited with the discovery of thallium, and is the inventor of the Crookes tube, an early (partial) vacuum tube. He got involved in spiritualism in the 1860s, and was president of the Society for Psychical Research in the 1890s.

Katie King was the name given to a spirit who was allegedly materialized by the medium Florence Cook, and others, in the 1870s. Crookes investigated Florence Cook, and avowed, controversially, that he witnessed a genuine Katie King manifestation. you will find that the celebrated Katie King appeared to him while he was alone in his study with the medium, Florence Cook, and that she appeared in all respects a woman of flesh and blood. She helped him raise the medium and deposit her more securely upon the couch. He took her pulse, and the medium's, and found them to differ by a number of beats per minute. He clasped her to him, and felt her solid form disappear into nothingness in his arms. All this, my dear Branscombe, is a matter of scientific report, made by one of the foremost physicists of his day, a man whose life work was the investigation of matter."

"But if you succeed in getting it to leave the child and go to Mrs. Sampson, what then?" I asked.

Martinus laughed in his dry way. "We shall try to slam both doors in

its face at once, and leave it out in the cold," he answered. "Did

you ever take part in an old-fashioned parlor game known as musical

chairs? Yes, we ought to have a very interesting time with this

phantom, Branscombe."

IN spite of Martinus's matter-of-fact manner, and my own former experiences, I could not repress a thrill of fear when, the preparations having been completed, we took our places in the temporary séance-room into which the Adrians' bedroom had been converted.

It was not the weirdness of the scene, or, rather, the contrast between that weirdness and the prosaic life of Yonkers going on outside—cars following one another down the street, voices of passers-by coming up to us through the shaded windows. It was the presence of the boy as the chief agent in what was being done.

A cabinet had been constructed by means of two cheap screens, fastened together, in an opposite corner of the room; the child's crib was also screened, and in that crib sat the little boy, wide awake, and chuckling over a woolly lamb that he was hugging. Mrs. Sampson sat in the cabinet, of course. Between this and the screened crib we four—the Adrians, Doctor Martinus and myself—formed a half-eircle. Outside, the twilight was swiftly fading into night.

As this night deepened in the room, it was uncanny to hear those chuckles coming from the cot.

"He's never been like this before," Mrs. Adrian whispered. "He always goes to sleep before this time. When he's awake he—he isn't like that, not with me in the room."

There was an indescribable pathos in her voice. Adrian muttered uneasily. It was evident to me that he had been dragooned into attending the séance, disbelieved in it, and resented it.

"Let us keep silent," said Martinus. Seated next to the cabinet in which Mrs. Sampson was, he leaned toward her. "Are you ready, Mrs. Sampson?" he asked.

"Ready," she answered in a faint voice.

A few seconds later I heard her sigh and begin breathing heavily.

"This is all nonsense!" muttered Adrian uneasily.

But it was eerie in that room, as the silent minutes passed, and now the child was chuckling no longer. I saw his mother trying to strain her eyes toward him through the darkness.

"Whatever happens," came Martinus' low tones, "please remember to keep

silent, and above all do not stir from your places under any pretext."

MINUTES more. A street car rumbled past in the distance. My hands

had that peculiar cold numbness that I always felt when something was

impending. I was straining my eyes upon the cabinet, from which I

heard Mrs. Sampson's uneasy stirrings and moanings. The black stuff

curtain that hung in front of it was moving to and fro, but that might

have been her hands.

"Oh, my God!" whispered Mrs. Adrian suddenly.

The curtain had partly fallen from one of the hooks that held it in position, affording a dim view of Mrs. Sampson's head and shoulders, barely outlined in the faint light that came from the sides of the window-shades. And about the woman's shoulders some filmy stuff seemed to be condensing.

"Silencel" Martinus whispered insistently.

A few seconds more, and the filmy stuff was clearly visible, as if lit by its own phosphorescence. And it was moving, moving slowly toward the front of the cabinet—a cloud, a faintly luminous cloud, perhaps like that which guided the Children of Israel through the desert. Shapeless, nothing but a cloud, it moved and swirled with innumerable tiny eddies, and behind it I could see the figure of the medium sunk as if in sleep, and I could hear her heavy breathing.

If the cloud was assuming shape, I could not see it. Sometimes I could see nothing, at others patches of mist seemed to float before my eyes. But of a sudden something happened that sent an icy chill down my spine. From the child's crib came a wild, shrill, chuckling laugh.

Never have I heard a human laugh so terrible as that, even from a grown man or woman. And following immediately upon it there came a scream from Mrs. Adrian:

"Oh, my God, Emma!"

What happened next I don't know. A chair was overturned, I heard Martinus land on both feet as if he had leaped from a height; there came an oath from Adrian, the sound of some one panting—then Martinus had switched on the electric light, and I saw Mrs. Adrian lying in a dead faint upon the floor, her husband kneeling beside her.

Mrs. Sampson sat slumped in her chair within the cabinet. One of the screens had fallen back against the wall. The child was silent in his crib, and Martinus was breathing heavily, as if he had been running.

"Too late, Branscombe," he whispered huskily. "If she hadn't screamed——"

Adrian looked up, his face twisted with violent anger. "Leave my house, all of you. I'm through with this foolery!" he said.

THREE weeks went by. Doctor Martinus had said very little to me

about the failure of his experiment, and of course I had not

questioned him. In the face of Adrian's attitude—he had practically

turned us out of his house—there was nothing more to be done. I was

absorbed in some abstruse work of Martinus' and had virtually

dismissed the affair of the Yonkers vampire from my mind.

Then one evening, as we were seated at Martinus' desk together, checking up some data—the subject had reference to the Einstein theory of light—the door-bell rang violently. Next minute the colored maid was showing in Mrs. Adrian.

The three weeks had worked a shocking change in her. There was hardly a vestige of color in her face, which looked like that of a corpse. Her skin was shrunken over the facial bones, her expression wild beyond anything I had seen.

She ran to Martinus and seized him by the hand. "Doctor, this can't go on!" she cried. "We are at our wits end. My husband is on the verge of insanity. He begged me to come to you and ask you to overlook the remarks he made to you at that séance in our house. If he hadn't I should have come to you anyway. We will do anything, literally anything, if only there is a chance that things will right themselves. Doctor, at night I go to the most frightful places. I can't remember what happens there, but—people without pity, Doctor, inhuman things ... and then our boy...."

Martinus laid his hand on her shoulder. "I know all about it, Mrs. Adrian——"

"And Richard and I go to the same place together. That is the horror of it. For a long time I wouldn't let him know that—that I had dreams like him, but now we know that we both go there. And they are dragging us there. It means insanity, death—and Bobby——"

She broke off, incoherent and frenzied. Martinus made her sit down.

"I thought you would be coming here soon, Mrs. Adrian," he said. "Of course I know your husband was hardly responsible for what he said that night. I believe we can yet find the remedy."

Before she left he had promised to be at the Yonkers house the

following evening for another sitting.

THERE was the usual prelude with Mrs. Sampson, who had come out of her trance in time to take some of Adrian's remarks to herself, and to feel accordingly offended; but Martinus soothed her ruffled feelings in his adroit way, and we three started up toward Yonkers as before. On the way the Doctor outlined his scheme to me.

"We're dealing with infinite cunning and determination, Branscombe," he said. "Not in the human way, of course. Judged by any standards at all, the people on the other side fall far short of us humans in intelligence, because they function there through instinct. But there is no doubt that the particular entity we are dealing with does understand in a dim way that we are laying a trap for it, and is resolved to outwit us.

"I told you, Branscombe, of my intention of decoying it out of little Bobby Adrian by the lure of Mrs. Sampson, and then slamming both doors on it. The trouble is that we were not quick enough to stop it. You saw the ectoplasm exude from Mrs. Sampson's body? That was, of course, the veil of the entity that has taken possession of the child, and left him in order to attain materialization through this good lady on your left, who is so busy reading 'Advice to the Lovelorn' in that paper of hers.

"The instant Mrs. Adrian screamed the ectoplasmic exudation returned to Mrs. Sampson, and the entity, relinquishing its sheath, became one with Bobby Adrian again. This time I hope to throw a barrage around it which will effectively bar its way."

"I've heard the old legend of a spirit being unable to step outside a circle of chalk, " I said.

"Not without a basis of sense, Branscombe. It is neither the chalk nor the circle, of course, but simply the disintegrating effect of white light, and, chalk being white, it might have something of the same effect.

"However, we have progressed beyond chalk. I have sent a certain

apparatus up to the Adrians' house, and I hope that this will do the

trick for us."

IT had arrived before we got there, and consisted of a small but

complicated apparatus somcthing like a projecting camera. There

was a circular slot arrangement too, and lenses, together with some

sort of clockwork mechanism that I did not understand. We carried it

up to the bedroom, where the child lay asleep in his crib.

But this time I could hardly repress a cry of horror at the sight of him. The whole of that child's body was suffused with scarlet, the lips were carmine as a painted woman's lips, and more dreadful still was the look of smug satisfaction upon the face as the child slept.

I looked from him to Martinus, who had left the apparatus that he was setting up, and had come to my side. Adrian, more ghastly than before, was standing in the doorway. Martinus made a gesture to me, hardly perceptible, indicating he wanted me to say nothing.

But to the mother's eyes nothing was amiss. She bent over the crib, fearful lest the boy should awaken. She looked up at us.

"Doctor, isn't he a strong, beautiful boy!" she said. "I can't believe that anything is really wrong, of the kind you've told us about. Oh, if I could only believe that you can drive this dreadful thing away and let us be as happy as we used to be!"

"I believe I can," answered the Doctor. "Only this time everything will depend upon absolute silence, no matter what you hear or see.'

"You shall see that you can trust me this time," Mrs. Adrian responded.

MRS. SAMPSON had taken her place within the cabinet. We four formed

the same half-circle, but in front of Doctor Martinus was the apparatus, standing on a tripod, and somewhat resembling a surveyor's theodolite. I wondered what part it was to play in the séance. But I should know soon enough. Already Mrs. Sampson was breathing hard and moaning inside the cabinet. Again I felt that cold wind on my hands. I saw the curtains swaying to and fro.

Then, curling out beyond them, I saw the strands and shreds of mist. But this time they seemed to be taking tangible form. And gradually, very gradually, through the darkness, I saw the outlines of a woman's figure grow against that silhouette of blackness.

Mrs. Adrian's hand in mine grew tense. She was breathing convulsively, almost as hard as the medium inside the cabinet. That shape, that terrible shape, was floating toward the half-circle. Suddenly I saw its face—and I was gripped by an uncanny terror.

"Emma!" shrieked Mrs. Adrian, "Emma!" and fell back, fainting, in her chair.

A face flat as a pasteboard mask, white as a death's head, the eyelids closed as it floated forward, the hands seeming to grope for something. I could not take my eyes off it. Suddenly that peal of wild, horrible laughter was repeated, but this time from the half-formed lips. And with that the cyes opened.

Eyes of blazing black, like pools set in the sockets, pools of blackness against the whiteness of the face. Eyes blazing triumph, scorn, and derision, as they fixed themselves upon Mrs. Adrian.

But she had suddenly grown limp. Her husband, at her side, was rigid in his chair, his head following the floating form with stiff, mechanical jerks. The figure stopped in front of us. And then—I could not tell whether it was the form that spoke or Mrs, Sampson in the cabinet:

"I've got my eyes open!"

"WHY have you come back?" asked Martinus.

"I told her. I've been wandering in the dark. I didn't know where I was, but I've got my eyes open now.

"You've taken the wrong road."

"No, the right road, the right road. I'll make her pay."

Martinus leaned a little forward. "There is no passing by this road. You must take the other road, the road of birth. This road was closed long ago, long ago, Emma Wishart."

"It's too long, that other road, and I shall forget."

"No one ever forgets. Go back. This road is closed to you henceforward. You have been wandering. You have forgotten. Go back now and let the dead bury their dead. That life of yours is ended, the balance is drawn, the account closed. Go back and take that other road."

A shriek of derision came from somewhere in the room. I saw Martinus' hand move, heard a lever click. Suddenly the figure was ringed with a flood of brilliant light, blazing between it and Mrs. Sampson, between it and the child.

The scream that followed sounded like a bedlam of fiends in hell. For one instant longer I saw the figure white against the darker background; then it had vanished. The light had gone out, and I heard the collision of two heavy bodies somewhere in the room. From Adrian's lips came a maniacal gibbering. I heard Martinus panting as he wrestled with some invisible adversary, and, groping, I found the electric light and turned it on.

Mrs. Adrian was sprawled in her chair, unconscious. Her husband was on

his feet, mouthing and gibbering. Upon the floor lay Mrs. Sampson, her

arms locked convulsively about Martinus' neck, her fingers twitching

at his throat.

IT was Martinus' custom to maintain a certain reticence about his

cases until some time had elapsed. Consequently, though I was

decidedly curious to understand just what had happened, I had to

wait his pleasure in this particular instance for nearly a month.

What precipitated the discussion was the appearance one morning of Mrs. Adrian, bringing with her little Bobby, apparently a perfectly normal child of his age, and clinging lovingly to his mother.

"Doctor," she said, "I shall never be able to thank you enough for what you did for us. My husband is well on the way of convalescence now. That terrible night was the end of all those horrors. You saved us both from insanity, and you have given me back my boy."

"A fine-looking little fellow,' said Martinus, pinching his cheek. "I needn't tell you to take good care of him, Mrs. Adrian."

"You know, Doctor, my husband and I have been talking over all this, and we have come to the conclusion that we must both have been badly run down, and imagined all sorts of stupid things. I'm not a sceptic, but of course one must use one's common-sense in such matters. There wasn't really a—a spirit in that cabinet, was there?"

"Well, not the conventional ghost—no, Madam," answered Martinus. "But Mrs. Sampson, my medium, is really adept——"

"Oh, you needn't go on," said Mrs. Adrian. "I knew it was she who came out of the cabinet, but still, I believe there is a lot of quite unconscious imposture. Anyway, I shall never criticize you because you saved my child."

When she was gone, Martinus turned to me with a smile of cynical amusement. "You see, my dear Branscombe? What chance has one of turning one's scientific discoveries to account, when the world is full of just such people as Mrs. Adrian?"

"Doctor," I answered, "you have never told me just what did occur. I imagine it was her husband's finding you at grips with Mrs. Sampson on the floor of the séance-room that brought about this change of attitude on Mrs. Adrian's part."

MARTINUS nodded thoughtfully. "This identification of the medium

with the form is the great stumbling-block to the lay mind," he said. "But you know, Branscombe, that since the form is built up out of the very tissues of the medium, both are identical. Thus, when one grasps the form, the medium is instantly projected from the cabinet into the very hands of the scoffer who has seized it, and of course, incidentally, his cry of fraud appears entirely self-evident.

"In this case, by instantly encircling the materialized shape with a band of light containing the ultra-violet rays, which are immediately destructive of ectoplasmic tissue, I threw an impassable barrier between the shade of Emma Wishart and both Mrs. Sampson and the child. We slammed both doors, my dear Branscombe, leaving the vengeful spirit out in the cold, with no prospect of working out its revenge save by passing through the legitimate channels of rebirth. And by the time she is able to accomplish this, you and I and Bobby Adrian will have long since been mouldering in the dust.

"I want you to understand, Branscombe," he went on, "that Emma Wishart is, or was, by no means consciously a devil. It was the impulse of the death-bed curse that carried her along. She was not consciously a vampire, nor did she wilfully prey upon her sister and her sister's husband through the medium of the child. All those doings were as unconscious as the doings of the newly dead man who, in his eagerness to inform his family that he is still alive, knocks down pictures and ornaments, flings lumps of coal, and generally raises cain with his antics, under the impression that he is merely signalling his presence in a decorous way. Given a wish, nature sets her own mechanism to work to fulfil it—and she generally sees that the wish is fulfilled.

"It was the intense desire to reassume material form that brought about the whole chain of circumstances. With Bobby Adrian's soul firmly in the saddle again, and ruling his healthy little body, I don't think there is much likelihood that his aunt will ever succeed in imposing herself upon him again."

"I wish the Adrians could understand." I remarked. "It seems, somehow, as if they ought to take a more intelligent interest in matters which concern them so intimately. It is pitiful that you should have to work in the dark, so to speak, when dealing with matters of such transcending importance."

"Yes," and Martinus nodded, "but if they hear not Moses and the Prophets, they would not hear one though he rose from the dead."

Part of the series Dr. Martinus, Occultist

Illustrations from Ghost Stories Magazine, October 1926