She lay in her crib, the weazened look of an old man on her features.

I HAD seen from the first that the séance was doomed to failure. Doctor Claude Merrick had inveigled three distinguished physicians into attending, and we had got into the usual rut. Charlie Wing, Merrick's Chinese boy, and a born medium, had been possessed, in turn, by the spirits of Queen Victoria, Mary, Queen of Scots, and Julius Ceasar, and was now writhing uneasily, prepatory to awakening to his natural state.

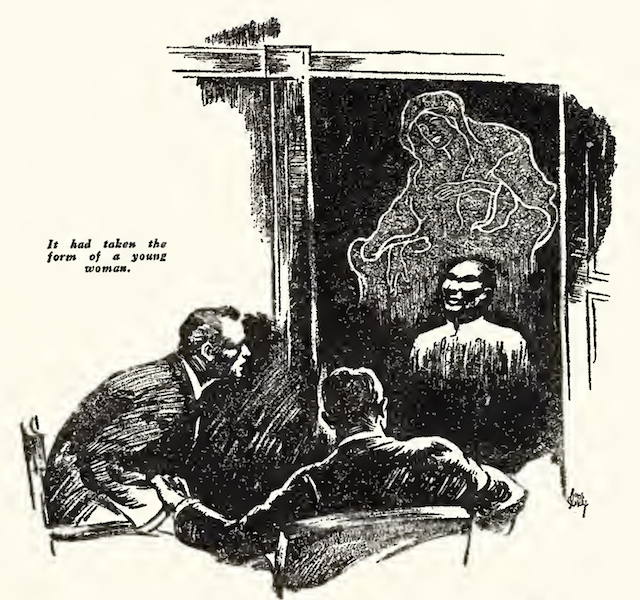

It had taken the form of a young woman.

And then it came, that brief "Help me! I don't know where I am!"

"Who are you?" asked Merrick.

"He is painting in his room. I can't get in. I can't wake up. I hate Milburn."

"But who are you?" asked Merrick again.

"Parlez-vous? Parlez-vous? came the answer. Then Charlie sneezed and work, and the séance was at an end. Merrick turned on the lights. The three physicians rose, looking bored and annoyed; a little ashamed, too, as if they had placed themselves in a ridiculous position.

"Very interesting, Doctor Merrick," said Forbes, the brain specialist. "It certainly does give one room for thought."

"A quite extraordinary exhibition," said Burroughs, the head of the State Hospital for the Insane. "Though you'll agree with me, I'm sure, that we shall have to go a considerable way further before we can apply your methods to the average case."

The third physician said very little, and looked frankly annoyed. Merrick ushered them out, a smile upon his lips. Charlie was straightening the séance room preparatory to serving dinner. Out of his trances he knew nothing that had occurred, and was just a good Chinese servant.

"Well, Benson, failure—rank failure," laughed Merrick, when he had got over his annoyance. "I warned those three wiseacres that they might expect just the sort of thing that has happened. Mischievous spirits, pretending to be the shades of the mighty dead; elementals playing pranks upon humans; astrals, discarded shells of thought, mere automata, attracted to the medium and pouring out the contents of their soulless minds in gibberish.

"I explained it all to them. I tried to tell them of the enormous difficulties. I begged them to realize that it is like the task of the pearl-diver, satisfied with one pearl out of a barrel of waste products. It didn't go. It never goes. These fellows demand an instant, logical explanation of heaven and hell and the hereafter, by James Johnson, late of the Union League Club, together with full proof of identity."

IT was disappointing. I might almost say, heartrending. If only the investigator would try to understand what he is up against! Imagine a public call-box, with the receiver off the hook, and a mob, all at the same time, trying to transmit messages, while half asleep, to various friends; also imagine a group of urchins interrupting them to shout opprobrious epithets or to play pranks, and you begin to get some notion of the difficulties of posthumous communication. But I had seen enough in my capacity as secretary to Doctor Claude Merrick to be convinced of the reality of inter-communication between the dead and the living.

As a physician of considerable reputation, naturally he did not court publicity. Yet, believing in the truth of this, believing, too, that nearly all cases of insanity are due to what is termed "possession," he felt it his duty to attempt to convince some of his own profession.

Charlie Wing's mediumistic powers had been discovered by accident. The boy had been Merrick's servant for a year before he was discovered entranced in the kitchen one evening, a piece of paper on the table, a pencil in his hand, and on the paper a certain message—but that is by the way. He was setting the table now with a bland smile on his yellow face, as if nothing had occurred that afternoon at all out of the line of his ordinary duties.

"Benson," said Merrick, "did you get that fragment that came through at the end?"

"About Milburn?"

"Yes. That was unusual, getting a name across, when the communicator could not give his own."

"You think that was real?" I asked.

"It sounded as if the communicator made a wild grab at the telephone just as the line was going out of business. Most of our veridical messages have come through in the same way."

"But what does Milburn signify?"

"It is a fishing village on the coast of Massachusetts. There is an artists' colony there, I believe, although I expect it has now broken up for the winter. You remember our case with the policeman who was painting landscapes under the guidance of the late Weathermore?"

I remembered that case. Weathermore, cut off in his prime, had inspired a young policeman to artistic powers to continue his work. In the end, Merrick had persuaded the dead man to abandon his attempts at continuing the vicarious practice of his art.

"I AM inclined to think," said Merrick, "that Weathermore was back of that communication. Somebody is in trouble at Milburn, and Weathermore is helping him while he is asleep. That is why he couldn't wake up, as he phrased it."

"Who can it be?"

"He gave his name as Parlez-vous," said Merrick thoughtfully. "Of course, that is is the sort of prank a low-class spirit or elemental would indulge in. At the same time, the difficulty of getting names across, except pictographically, is enormous."

He paced the room. Charlie had set the soup on the table, but Merrick, deep in though, seemed not to perceive it, and I knew he would not appreciate having his attention called to the matter.

Suddenly he stepped into the office adjacent and came back with a copy of Who's Who. He turned the pages rapidly.

"Here you are, Benson," he said. "Born 1887, educated at Groton, studied art in Paris. Exhibited, et cetera. Married, first, Georgiana McLaren, daughter of Ian McLaren, of Boston, 1912; second, Millicent Hayes, daughter of James Hayes, of London, 1926. Daughter, Elsie, born 1928."

"Well?" I asked.

"It was Weathermore who was at the back of this, Benson," said the doctor, closing the heavy volume. "Very clever of him getting that word Milburn across like that, with Mary, Queen of Scots and Julius Caesar cluttering up the wires. But I'm not so sure the message has reference to him, after all. It said that 'he' was painting in the room.

"If it was Weathermore, he wouldn't have gone to all that trouble to communicate unless this person is in desperate need of help," continued the doctor.

"But, Doctor Merrick," I said, "you haven't told me who this person is, or how you got his name," I protested.

HE stared at me. "Eh? What's that? I thought I'd told you," he answered. "Why, our friend Parlez-vous, is French—Alfred French, one of the most representative of modern American painters. Rather ingenious of our friend Weathermore, wasn't it? But I'm inclined to think it was his wife who sent out that appeal for help while resting this afternoon.

"Come along, Benson, the soup's getting cold."

I think it was the doctor's realization that Weathermore would not have asked his aid in any ordinary case that decided him to go down to Milburn. Fortunately it was not difficult to obtain a note of introduction to French, and, after registering at the local hotel, we strolled along the shore road to French's bungalow.

There were some half-dozen houses and bungalows standing along the shore, but all except French's had been closed for the winter. His was the last of all, a long, old-fashioned, single-story cottage standing on the very edge of the low cliff, with the Atlantic breakers roaring underneath and tossing foam almost to the doorstep.

It was a desolate place, even in summer, and much more so now, with the few straggling birches almost denuded to their withered leaves, and that expanse of sea and sky, and the roar of the ocean perpetually in one's ears. There was an eery feeling about the cottage, too, which did not decrease as we stepped up and Merrick rapped with the ancient brass knocker upon the dented plate.

IT was French himself who opened the door—I remembered having seen his portrait somewhere. His hair was disordered, his face anxious.

"My name is Merrick—Doctor Merrick," my companion began.

"Thank God, you've come, Doctor," answered French. "My wife has been asleep since two o'clock this afternoon, and I can't wake her up!"

Without further explanation, Merrick entered the cottage, and I followed at his heels. French led the way into a large bedroom, tastefully furnished in Colonial style. Beyond it I could see his studio, with paintings on easels. On the bed lay a young woman, apparently fast asleep. Her face was flushed, her eyes closed, her breathing stertorous. In a crib beside her, a child of three was sitting up, playing assidously with a doll. She raised her eyes solemnly to ours, and then returned to her doll without a word. Her face was strangely white.

Merrick stepped to the bedside and raised the woman's arm. It remained extended stiffly in the air. He made two or three passes over her face and snapped his fingers.

"Wake up!" he commanded her.

Instantly the arm dropped. The woman opened her eyes, looked as us in surprise, and sat up.

"Why Alfred, what's the matter?" she inquired, in astonishment.

FRENCH, overcome with gratitude, and a little awed, had readily agreed to Merrick's request that we should let his wife believe we had been called in to treat her. He promised to make full explanations later, and Mrs. French's state of health certainly called for attention.

"I never feel well here," she told us. "All last summer I was upset, but this summer I've been worse than ever before. But Alfred loves this place, and so I agreed to remain until the middle of November. You see," she added, "he used to come here with his first wife, Georgiana, year after year. She died here suddenly, seven years ago. She's buried in the old cemetery on the hilltop.

"You may say I'm foolish to accede to his wishes," she went on, "but, you see, Alfred's art means everything to him, and then we are very happy together. And Elsie needs the sea air. You may have noticed—"

Merrick nodded, "Anemic, decidedly," he said. "But how about yourself, Mrs. French? What is the chief trouble?"

"I think it began with worrying about Elsie," she answered. "She was so healthy when we came here in June, and almost immediately she began to be sick. We've had several doctors here, including Messenger, who came all the way from Boston, but they can't find out what's the cause of the trouble, and all they advise is to let her have the benefit of the sea air."

"But your own symptoms, Mrs. French?" asked the doctor again.

"I can't sleep from worrying," she answered. "And when I do sleep, I sleep for hours, and Alfred can't wake me. And I have the most dreadful dreams."

"Ah, and can you describe these dreams to me? I mean, any dream that seems to recur pretty constantly?"

"I can't remember a thing, but they're terrible beyond imagination. I know that I try to wake, and I can't wake. And then I'm afraid to go to sleep again, and all of a sudden my eyes close, and—"

She began sobbing hysterically, and Merrick questioned her no further.

PUTTING little Elsie to bed was a rite, as in so many American families where everything centers about the child. First, French had to ride her on his back up and down the studio, and pretend to be respectively a slow old horse, a spirited charger, and an elephant. Then Millicent French had to tell her stories, with dramatic impersonations, being successively, father bear, mother bear, and baby bear.

And then came the rite of the doll. For George had to be disrobed, with pretense of bathing, and robed in his nightgown, and rocked to sleep, and finally laid upon the pillow beside his little mistress. Only then did Elsie consent to having the light put out, and even then there were two farewell kisses.

"Has your little girl always insisted that that is a male doll?" asked Merrick of French, when the parents had finally disposed of their offspring.

"No, she thinks it's a girl doll," he answered, "but she insists that the name is George."

"How long has she done that?"

"Since we came here this summer. As a matter of fact, my first wife's name was Georgiana," he added. "It's possible that the child has heard the name mentioned, although naturally my wife and I seldom refer to her. I hope you two gentlemen will have supper with us," he added. "We can't offer you very much in the way of a meal, but if you can stand—"

"We'll be delighted," answered Merrick promptly.

We sat down to cold ham and tongue, a salad, and some dessert that did credit to Mrs. French's cooking. After the dishes had been cleared away, Millicent French withdrew, apologizing for leaving us.

"I really believe I'm going to have a good, sound sleep tonight," she said. "You've done me good in some way, Doctor Merrick."

She looked very charming as she smiled and bade us good night.

I HAD anticipated that explanations would be somewhat difficult, but to my surprise this did not prove to be the case. French had known Weathermore, and he was not unfavorably disposed toward the consideration of psychic matters. The doctor told him frankly of the communication.

"It's all very extraordinary," said French, leaning forward in his chair in the big studio. "As a matter of fact, I've—I've been afraid the influences here were not exactly good for either my wife or daughter. The truth is—well, my first wife and I were very happy here."

He sighed, "You see, Elsie and she were friends," he said. "I felt that in a way it brought us all closer together. You see, as I told you, I am a believer in—"

I am going to speak frankly to you, French," Merrick interrupted him. "You have made a monumental error, and you are likely to pay dearly for it. You believed that the dead are in intimate association with the living, thinking the same thoughts, actuated by the same feelings as when they were alive."

"Isn't that so?" cried French, starting up in his chair. "Do you mean to tell me—?"

"I mean to tell you," answered Merrick, "that the boundary which was set between the dead and the living was never meant to be crossed. If crossed at all, it must be under expert guidance."

There was a solemnity about his tones that impressed us both with a sense of awe, almost of terror.

"The dead," said Merrick, "however intensely they long to revisit those whom they loved, can only re-enter this sensory life as we enter the astral world—in sleep; that is so say, in dreams. To them, everything is distorted, changed, and on their plane matter is so plastic that their wishes insensibly create new situations which they mistake for reality.

"I have known a father, who loved his child beyond anything on earth, and sought to revisit it. He did so as a haunting poltergeist, flinging crockery around, knocking down pictures from the walls, terrorizing the child he loved with hideous manifestations, and all this without the slightest idea that he was causing trouble or making his presence manifest at all."

"Then," said French in a shaky voice, "you mean that Georgiana—?"

MERRICK did not answer him for a while. Presently he spoke again.

"It is fortunate that Weathermore sent me here," he said. "I must tell you frankly, French, that the disease has, in my opinion, already progressed so far, that, even if you were to leave Milburn immediately; if you were to burn down this house and plough up the ground on which it stands, it is unlikely it could be cured."

"Do you mean—good God, do you mean that Georgiana is the cause of—of my wife's and daughter's illness?" asked French.

"But my dear sir, you summoned her, did you not, even though the call was partly an unconscious one? Did you not come here with the idea of entering into a sort of communion with her? That desire reached far into the next world, French."

French said in shaky tones, "She always wanted a child. It was the unhappiest thing in her life."

Merrick nodded gravely. "I see that your own diagnosis is pretty correct," he replied. "You probably realized that your wife was in a cataleptic state this afternoon? You know what that portends?"

"That she was in an abnormal condition. That she—she—"

"That she had been thrown into a mediumistic condition, not necessarily by your first wife, but by the elemental influences that are always waiting to rush in and obtain sustenance at the expense of human beings, just as humanity preys upon the beasts, and the beasts upon the vegetable kingdom."

Again there was silence. "What am I to do?" asked French.

"With your permission, I am going to keep watch in the bedroom tonight," answered Merrick. "Perhaps you will permit Mr. Benson to stay there with me. At what hour does your wife fall asleep?"

"Now it is curious you should have asked me that," French answered. "Invariably at twenty minutes before one. It—it is the hour at which Georgiana died," he added in a shaken whisper.

IT was exactly twenty minutes before one when French came back into the studio and informed us that his wife was asleep. We went in softly. Millicent French was fast asleep, but her breathing was natural, her skin moist and of a natural color. In the crib beside her the child slept, clutching the big doll in her arms. There was nothing eery about the room. Outside, beneath the cliff, the sea splashed softly. There was a half-moon in the sky, casting a flood of silver through the windows.

Merrick drew up two chairs beside little Elsie's crib and sat watching her. I wondered why it was the child he watched instead of the mother. I sat down beside him, while French flung himself into a big armchair at the side of his wife's bed and sat there, his head in his hands.

Detail from The Doctor by Luke Fildes (1891). Source: Wikimedia

The pose Merrick assumed, his air of quiet watchfulness reminded me of Luke Fildes' celebrated painting of "The Doctor." Strength seems to radiate from him. I knew that, what human being could do, Merrick would do. A small clock on the dressing-table ticked away the minutes.

It seemed close in the room, despite the season and the fact that the window was partly open. Time and again I felt my eyes closing; then I would open them with a sudden start, always to see Merrick seated there, watching. I could see the hands of the clock in the flood of moonlight. It was two o'clock now. Nothing had happened.

Then slowly a feeling of intense depression began to overcome me. I seemed to feel another presence in the room. It was nothing evil, but something bewildered, baffled, groping through darkness. The feeling of closeness was becoming accentuated.

The next thing I knew, I was lying on a lounge in the studio, and a flood of sunlight was streaming in through the window. There was a smell of coffee. Merrick came briskly out of the kitchen, carrying a tray with plates and cups.

"Awake, Benson?" he asked. "Don't worry; I slept, too. It was too strong for us. But you pretty nearly got into the cataleptic state. We're starting back after breakfast to get Charlie. He's about the last hope for the Frenches."

I WAS shocked to see the change in Millicent French and Elsie when we returned with Charlie Wing on the following day. Mrs. French was almost in a condition of collapse, while the child had lost all the energy she had shown on that evening of our arrival. She lay in her crib, looking like a little waxen image, and clutching the doll tightly in her arms. There was the weazened look of an old man upon her features.

French had told his wife that Charlie had come to help her till she grew stronger, and she had not the energy to ask any questions, but seemed to accept our presence as natural.

"Tell me, Doctor Merrick, is there any hope?" he asked late that afternoon, while we three sat together in the studio, and Charlie scoured the dishes in the kitchen, whistling a cheerful tune the while. "That Chinese boy of yours—is it possible he can be of any assistance?"

"Charlie is one of the best mediums I have known," responded the doctor. "I can say no more than that. Tonight, my friend, we shall either free your wife and daughter from this influence forever, or—"

He shrugged his shoulders. "If we win through, French," he said, "remember for the rest of your life that the paths of the living and the dead lie in different directions, and never make that mistake again."

He turned to me. "Benson, I think I'd like to take a little stroll to clear my brain," he said. "Will you come with me?"

WE left the house and struck inland across a field, following a narrow road with the dead stalks of goldenrod waist-high on either side of us. Crows flapped and cawed on dead stumps, or wheeled noisily into the air. A little distance back of the house was the old burying-ground. It contained some twenty-five or thirty graves, the headstones, which had all either tilted or fallen, dating back to a century before in some cases. It was not difficult to locate that of French's first wife, if only for the comparative newness of the stone. A wreath of immortelles lay on the mound.

Merrick stopped and read the inscription.

"'Let her rest in peace,'" he commented, translating the three Latin words. "Easier said than done, French. Your idea of letting her rest in peace, poor soul, is to set off an alarm clock in her ears!"

He turned to me. "Benson, there's a spade under the back seat of the car," he said. "Please bring it here at once. And don't let French see you."

We had parked the car just around the curve of the shore road, and it was not difficult to get the spade and strike a course back behind the untenanted cottages without French seeing me. But Merrick's sudden order had filled me with apprehensions of terror. It was only too easy to guess the purpose in his mind. My every instinct revolted, and with that rebellion cam doubts of the whole business.

Suppose Merrick was self-deluded, Charlie Wing an impostor, the whole French affair cleverly staged by the Chinese, and Millicent French and the child simply the victims of some obscure disease? To violate the sanctity of the grave, and unknown to French himself, seemed to me intolerable.

BUT when I saw Merrick waiting quietly beside the mound, the strength that always radiated from him calmed my doubts. As if understanding my state of mind, he said:

"There's no need for you to wait, Benson, if it disturbs you. Suppose you stroll back slowly, and I'll rejoin you presently."

"No, I'll see this thing through," I answered. "But are you sure—?"

He clapped his hand on my shoulder. "I'm as sure as I've ever been sure of anything," he replied.

With that he set to work. With a strength of which I had believed him incapable, he began digging into the mound and tossing the clods aside. It was worse than eery, it was horrible, to see him progressing in the failing light, with those birds of ill omen sitting on the stumps and rails of the decaying fence, and watching him.

Soon Merrick was below the ground, only his head and shoulders showing, and these disappeared from my view as he dug deeper, flinging up great shovelfuls of earth beside the trench. He was still working with undiminished energy. I stepped to the side of the grave and volunteered to take my turn at the work, but he only shook his head and went on.

NEVERTHELESS he was fully a half hour at work before I saw a corner of the coffin come into view, and it was ten minutes more before the casket lay completely exposed to view. Then Merrick inserted the blade beneath a corner of the rotten wood, and began to lever at the lid. That was when I stepped back, so as not to see.

But I could hear, and I shuddered as I heard the sudden rending, splintering sound which indicated that the lid had given. Involuntarily I closed my eyes.

"Come here, Benson," called Merrick.

Mastering my horror with a supreme effort, I stepped once more to the side of the grave. I opened my eyes and looked down. But all that I could make out inside the coffin was a heap of white bones and a few little mounds of dust.

Merrick leaped up and caught me as I reeled. For a moment everything went black. Then I recovered myself and stood unassisted.

"It's—it's all right," I muttered. "I thought—"

"Why, what's the matter, Benson?" asked the doctor in evident astonishment. "What was it that you expected to see?"

But suddenly he understood what had been passing through my mind. "Did you expect to see flesh and blood inside the coffin, man?" he asked. "No, no, Benson, I assure you you're on the wrong trail altogether."

Yes, it was true—I had expected to see something far more terrible than a mere heap of moldering bones. And I was mystified beyond measure as the doctor laid down the spade and motioned to me to accompany him back to the house.

IT was no use asking Merrick questions or demanding explanations before he was ready to volunteer statements. So much I had learned at a very early date in our association. When he was ready, he would explain, and until then I must just be content to puzzle out my own solutions in my mind.

But what had been the purpose of opening the grave and leaving it open? Had Merrick really expected to find nothing but bones in the coffin? Again my doubts returned. I was in a state of considerable agitation by the time we got back to the bungalow.

Charlie Wing was hard at work with the dinner in the kitchen, and whistling discordantly in his usual cheerful manner.

It was a sorry meal that we three sat down to. The child had fallen asleep, and Millicent French had refused to leave her; Charlie had brought her a light meal, but she had only drunk a little tea. French declined to eat anything. I saw his haggard eyes watching every movement that the doctor made. There appeared to be resentment in them now. He was in the state of mind when an explosion is imminent.

"I've had enough of this fooling!" he shouted suddenly, starting to his feet. "Leave this house, the three of you! What do I know about you? You two came here with a lot of poppycock, and then you brought in this Chink! How do I know what your schemes are? Leave this house, I tell you, or, by God, I'll kill you!"

HIS voice rose into a shriek. He leaped across the room, snatched a revolver from a drawer, and pointed it at Merrick's head. "Now will you go?" he shouted, his face working with maniacal anger.

The doctor looked at French without any change of expression. He moved his hands almost imperceptibly in front of the enraged man's face, snapped his fingers, reached out and took the weapon and slipped it into his pocket. French stared at him with a bewildered look.

"I feel—queer," he said, clapping his hand to his head.

"Go and lie down, my dear fellow," replied Merrick. "You'll be feeling better presently." And, as French stumbled away, the doctor turned to me with an expression of satisfaction.

"Well, that's the best thing that happened yet," he said. "You don't understand, Benson? You realized that French was temporarily obsessed, that he didn't remember when I awakened him?"

"Yes, but—"

"It means that certain entities across the river, whom I might call evil companions of that unfortunate woman, are getting alarmed. That was their little challenge to us. But when you face the elementals boldly, they slink away."

IT was a little after twelve when we adjourned to the bedroom for the séance. French had been quite himself ever since his outburst, of which it was evident he retained no recollection. The doctor had given Mrs. French a pretty strong hypodermic of morphine, and she was fast asleep. In the crib beside her lay Elsie, clasping the doll in her arms.

Our preparations were simple. A clothes closet in the corner of the room served as the dark cabinet, and Charlie was ensconced there in a chair, a broad grin on his yellow face. I am positive he had not the least idea what happened when he was entranced, but just what he thought he was doing I had never been able to make out. Three chairs were set out in front of the cabinet, but in such a way as to bring the child's bed—the foot of it—into the semi-circle. Then the lights were extinguished, and presently Charlie began to moan and breathe heavily.

It was a scene to which I was well accustomed. In a little while the communications from Julius Caesar and the rest of them would begin. Some mediums have their guides who assume control and chase away those mischievous entities, but for some reason or other Charlie had always been an open telephone line, and we had had to rely entirely upon our judgement as to the validity of what came through.

But each medium has his peculiarities, and, on the other hand, Charlie Wing was that rare being, a materializing one. I had seen too much to doubt this. I had seen the ectoplasmic swirls take the forms of heads and limbs, and we had a nice collection of photographs which, as Merrick had often said, were too obviously genuine to carry the slightest weight with persons whose judgements were preconceived.

On this occasion I waited with more anxiety than ever before; with a feeling of anxiety that approached terror. I had seen by the look on Merrick's face before the lights went off that he was in a state of extreme tension.

And as I sat there I was wondering about the open grave, and what he had expected to find in it.

THE manifestations came suddenly. From Charlie's lips issued a confused muttering, as of a number of persons all trying to talk at once, struggling, jostling each other. If that was fake, it was the work of a master. Then a deep voice, a man's voice, "Get away from here, all of you!" And then, more startling in its dramatic quality, "Merrick! Merrick! Where are you! The light is blinding me! I can't—hold on—for long."

"I'm here!" said Merrick.

"I'm—I'm—" Again the eternal difficulty of getting a name through. "The fog—the rain—sunshine—barometer—"

"Yes, I know you, Weathermore!"

"Yes, Weathermore. I—I'm bewildered—coming back. So difficult! I've tried to tell her, but she doesn't understand. They're fooling her, that crowd of devils round her, and she's good. She's good, but she doesn't understand. I want to help him—confrère—painter—gay Paree—"

"Yes, yes! Go on!"

"They're stronger than me. I—can't—hold—on—"

The voice ended abruptly in a high-pitched cry like a woman's. Then followed utter silence, save for the heavy, stertorous breathing that came from the lips of Millicent French, and from her husband's. Both were asleep, but this time I had no inclination to sleep. I sat crouched up in my chair, oppressed by the most awful fear that I have ever felt. It was as if all the devils in hell were about to launch themselves into the room.

Faintly, very faintly in the little light that filtered through the window, I could see Charlie twisting and squirming in his chair. Now and again a moan broke from his lips, but no voice came from it.

I know what that silance meant. It was the prelude to a materialization. With Charlie—I don't know how it is with other mediums—voices and materializations never came simultaneously. It was as if he needed all his powers for the one thing or the other.

Stronger and stronger came that sense of evil. It seemed to me now as if the doctor and I bore the whole burden of the fight upon our shoulders.

IT was beginning to grow luminous within the closet. Slowly Charlie's face was beginning to stand out against the background of darkness. It was covered with a filmy cloud, slightly self-luminous, a cloud that was almost imperceptibly detaching itself and gathering itself together.

Little ripples seemed to be running through it in all directions, as if it was a mass of unstable jelly, so fast that it was impossible to say which way the cloud was moving. It circled about the face of the entranced man, now right, now left of him, forming into swirls that momentarily seemed to take the form of a face, of an arm thrust out through a mass of draperies, and then resolved itself again into an undifferentiated mass. And then I heard a sound behind me—the creaking of bed springs.

I glanced back. Millicent French was rising from the bed. But she was rising as one might picture the dead rising upon the Day of Judgement. And that sight still haunts my memory as the most dreadful of all the things I saw that night.

Jerkily, foot by foot, she rose, till she was seated on the edge of the bed. Then, with the same jerky succession of movements, she was crouching upon the flookr beside it. She was rising, her knees had straightened, and she now stood upright. And now she was moving toward the cabinet, with arms extended stiffly in front of her; and dark though it was, I could see that every muscle of her body was set in the rigor or complete catalepsy.

FORWARD, slowly, hesitantly, as a soul awaiting judgement might move toward the dread seat, moved Millicent. She was coming straight toward us, and I looked at the doctor, not knowing whether he meant to break the circle and let her pass through. But instead of passing me, she moved toward the foot of the child's bed and stood there, arms still outstretched, but as if in protection.

And then I saw the ectoplasm within the cupboard take shape with astounding rapidity. One instant it was a whirling cloud—the next, it had taken the form of a young woman!

A wraith, a phantom built up for the time by the personality behind it. Only a phantom, for it was indistinct at the edges, and I could see that the trailing draperies concealed gaps that had not been covered—at the back of the head, the back of the body. It was barely more than two-dimensional, a flattened silhouette, and yet curiously, horribly real.

I never read or saw of any more stupendous drama than the one enacted in pantomime before me, as the dead woman and the living one confronted each other. And to my mind the chief horror of it was this, that the two, the living and the dead, were merely masks.

Of the dead woman, this was certainly the case. But of the living, it was also true, for what was Millicent French but a shell, a mask, almost as devitalized as the thing that faced her? In stark horror I watched the two draw near, until the outstretched arms of the living woman almost touched the dead one inside the circle.

NOT a sound came from either, but I could see a look of fear growing in Millicent's eyes. And her arms, which had been extended in front of her, were being bent back until they were stretched out horizontally in front of the crib. I saw an expression begin to dawn upon the face of the ghoul, a look of triumph, of ecstacy. ...

Then suddenly she was gone! There was only the living woman standing at the foot of the crib. But her arms were jerking downward, and then, in the same rigid catalepsy, she stood, a marble statue, to all appearance, inanimate.

There was now no objective phenomenon within the room. The cloud of ectoplasm that had been about Charlie's head had vanished. For a moment I thought that the séance was over, that Merrick had banished the phantom and robbed it of its power.

Then I saw Merrick glance back toward the crib, and I saw something that almost drove the last remnant of sanity from my brain.

For the doll that the child had clasped all the night in her arms had grown somehow swollen—monstrously distended. The face had grown larger, the lips redder, and the eyelids seemed to tremble, while the eyes beneath them seemed to reflect an evil light.

Then, even as I looked, a tremor ran through the doll's body. It stirred, it turned, and those red lips were implanted full upon little Elsies's!

MERRICK'S hand fell upon my wrist with a grip of steel. "Keep your head, Benson," he whispered. "We've won! We've won! God, I scarcely dared hope that she would take the lure! Keep by me!"

As he spoke I was conscious that the evil which had oppressed me had vanished, and it was like the lifting of a heavy cloud. I could see Charlie slumped forward in his seat. Millicent French had collapsed across the bed; her husband was still breathing heavily in his chair. Quietly I stepped toward the crib and looked down at the hellish thing that lay clasped in Elsie's arms.

It was alive! It was flesh and blood, and yet through the flesh I seemed to see the framework of the doll. But it was alive, for there was a flush of blood in the cheeks, and the horrible red lips were growing redder.

And as I looked I seemed to see the child grow even more waxen, as if its life-blood was being drained into the doll's body.

"Keep your head, Benson," whispered Merrick to me again, and stepped to the side of the crib. He stooped and placed his hands about the monstrous thing at Elsie's side.

It was smiling evilly, and, when Merrick tried to pick it up, it still clung to the child with its stumpy hands, and the red lips were withdrawn with an audible suction. It lay in Merrick's arms, squirming and still smiling.

"Come!" he whispered to me; and, carrying the horrible burden, he made his way out of the house. I strode after him over the field. I knew where he was going now, and I could hear the thing making plaintive little mewing noises, which grew fainter, until, by the time we reached the graveyard it had grown silent.

THE moon had nearly set, but by the light of it I could still see the thing, faintly squirming. The eyelids opened, and it looked up piteously into Merrick's face.

Merrick poised himself upon the edge of the open grave and hurled it down into the coffin. I heard the yielding thud, as of flesh, as it struck the bottom.

"The spade, Benson, the spade!" he called, as he jumped down after it and began frantically adjusting the lid of the coffin.

I leaped down after him, spade in hand. A plaintive mewing was coming from within the coffin. There were feeble blows against the lid. And the most dreadful thing of all was the appearance of a stumpy hand, that seemed half flesh, half wax, between coffin and lid. Merrick thrust it back with the edge of the spade, and began dragging down the earth from the sides. And all the while that piteous mewing went on, till the increasing weight of the earth smothered it.

But I can tell no more. I only know that I crouched beside the grave, watching Merrick at work, watching him stamping down the shovelled-in earth, and gradually growing taller, until at length he emerged, and only a low mound, as before, marked the site of his work.

He had carefully cut away the sods, and these he now replaced and stamped down in turn. As far as I was able to judge in the faint moonlight, no evidences remained that the grave had been tampered with.

THEN only did Merrick drop on the grass beside me and wipe away the sweat that streamed from his forehead. For a while he was too exhausted to talk.

"Well, we've won," he said at length. "It's all over."

I said nothing, and he went on. "You understood, didn't you Benson? She—the dead woman—had wanted a child. So little Elsie's doll became the focus of all the devil's work that was taking place. It was the doll that was draining the child's life-blood nightly, although it was only when Charlie Wing came on the scene that the spirit was able to materialize into a definite shape.

"You must not think that that poor woman was aware of what she was doing. But there are always elementals ready to lend their aid to anything and everything that affords them their supreme desire of coming into touch with mortals.

"I saw that it was touch and go. The only hope lay in materializing this astral shell of the dead woman—a thing entirely automatic and devoid of knowledge or responsibility. I hoped that it would gravitate automatically to the doll instead of returning to the astral sphere, ready to plague the Frenches again. That hope was gratified, and now, six feet beneath the earth, it will slowly molder until its final dissolution sets the dead woman free from the earth-bound condition into which her love and desires plunged her."

"DOCTOR, I'm feeling so much better today, and Elsie seems better too, though she's so weak. I've got a feeling that the worst is over, and that we're both going to get better from now on."

"I can assure you of it, Mrs. French," answered the doctor. "I am so certain of it that Benson and I are starting back to town this morning. If you should need us again, we are at your disposal, but I'm quite sure everything will be fine from now on."

"That must have been wonderful medicine you gave us," said Millicent vaguely. "But do you know, Elsie's hidden her doll away and won't tell me where she's put it. Where's dolly, darling?" she asked, as the child toddled into the room toward her mother.

"Baby buried old dolly, nasty old dolly," answered little Elsie. "Baby buried horrid old dolly last night, in the ground."

"Now, did you ever hear such fancies?" asked Millicent. "Last night she wouldn't go to sleep without her doll, and now she hates it."

"I've got that feeling, too," said French, as we stood at the door. "You hypnotized us all last night, didn't you Doctor? I know I slept like a top, and I'm feeling like a different man. But I'm still afraid for Millicent and the child."

"Nothing more to be afraid of, if you remember my warning, French," replied the doctor. "One life at a time, now and henceforward."

"All leady, Mastah!" came Charlie's cheerful voice from the car.

So with a final wave of the hand, Merrick stepped out into the bright sunlight, and I followed him.

Part of the series The Occult Detectives of Victor Rousseau