Why should anyone—man or ghoul—want to torment an innocent child?

But, my dear Mrs. Temple, why were you not satisfied to let well enough alone?" demanded Doctor Martinus brusquely. "You had established a little shrine in that room of yours. You had filled it with happy influences. But you were not content to leave that little haunt for the hallowed spirit to revisit in its dreams. Why did you throw that bolt into the mechanism of the astral universe?"

"Well, Doctor, you know people were beginning to talk about it, and to say that my mind had become unhinged through brooding. And my friends said it was heathenish. They told me that my dear little Doris is now an angel in heaven, and that I shall meet her there when I die, but until then there is no possibility of our knowing anything about each other. And so I—"

"Here is your Mother, Doris," came the Doctor's voice.

"Mamma, where are you?" The voice piped. "I can't find you. I've been looking for you. I'm all alone."

"And so you ran to a charlatan, a mere dabbler in psychic matters—of which he is, and always will be, ignorant," said Martinus savagely.

"But, Doctor—Mr. Craven has a very strong spiritualistic power, and he assured me that he could lay the spirit for ever, and so I let him try."

"And instead of the little shrine, you got a full-blown haunted house," said Martinus. "How long after this man Craven performed his operations in that room did these manifestations begin?"

"Three or four days, Doctor," said Mrs. Temple tearfully. "At first I thought it was my darling Doris—"

"Pulling hair and pinching, and throwing glass and crockery!" Martinus snorted.

"Mr. Craven said it was an after-manifestation that would soon disappear."

"And what did your heart tell you?" demanded Martinus.

"Why, it—it told me—"

"It told you it was a devil, and it was right!" the doctor shouted. "Very well, madam. I'll come, and see what I can do. Hereafter, rely more upon your Bible and less on fools like Craven, and remember the passage about the seven devils. You drove out the legitimate tenant, and its place was taken by one devil—or seven. That we shall see. Good afternoon, Mrs. Temple."

Doctor Martinus turned to me when our visitor had departed.

"Sometimes, when I get a case like this, I almost despair, Branscombe," he said. "That Mrs. Temple is the wife of a wealthy mining man, now out West. They have a big house, here in New York. Last year they lost their little girl, and she was almost distracted with grief.

"She did what the natural instinct of nearly every mother bids her

do. She collected the child's toys, and her favorite doll, in the

bedroom, and turned the place into a little shrine—just as the

Japanese do when their loved ones die. And because the act was so

simple and so natural, and because nothing that is evil can pierce

the armor of a mother's love, she turned that little room into a

channel through which the loveliest influences descended to bless that

home.

"YOU CAN picture the dreaming soul of the child, revisiting its home, and finding there everything that it had known—its toys, a mother's love, and the mother who spent a good part of her time there, sewing, or doing other domestic duties, because, as she expressed herself, 'It was the happiest room in the house.'

"What happens? The neighbors begin to talk. They say her mind has become unhinged. Then her friends persuade her that it is a heathenish practice—-that the dead are cut off for ever from the living. So, she goes to this man Craven, this quack spiritualist who knows nothing whatever about the real spiritualism, and—he comes on a visit of inspection!

"He sees the doll and the toys, and he persuades the mother that the spirit of her child has become 'earth-bound' (as he phrases it), and that the mother is wrecking her child's heavenly happiness by drawing it down from realms of bliss to an earthly environment. As if there could be any greater bliss in heaven than the remembrance of a happy childhood!

"What does he do? Mumbles some incantation, perfectly efficacious, not because it is a charm, but because of the intent that underlies the words. This faker breaks up the shrine, lays the doll away in a cupboard, turns the bed and furniture around so that the child shall not recognize the room, and goes away telling the mother that the 'spirit is laid.'

"That was six weeks ago, Branscombe. Three days after that the manifestations began. Our friend Craven had turned the shrine into a typical haunted house."

I had not been in the room during the beginning of the Doctor's conversation with Mrs. Temple. "You mean that noises are heard, things thrown about, and so forth?" I asked. "And I heard something said about pinching and pulling hair."

"Yes, all the typical phenomena of the poltergeist." responded Martinus, "And that ass, Craven, insists that these manifestations proceed from the spirit of the child, angry that it has lost its earthly home. Stark nonsense!"

"I remember," I said, "you once told me that these noisy hauntings generally had a merely physical explanation. You referred to the fact that in every such case, as reported from time to time in the newspapers, there appears to be present a boy or girl of about fourteen years, and that the child is subsequently supposed to be detected in trickery."

"I alluded to the simple explanation which, so far as I have read, has always escaped the notice of spirit investigators—that, with the advent of maturity, the etheric, or so-called 'astral' body on which the human frame is modeled, becomes capable of enormous extension. The child discovers that it has the faculty of throwing articles—-glassware, or crockery—from a distance, by grasping with the extended etheric hand. When it is detected in the act of throwing, even from a distance, the trick is proclaimed and the explanation is considered obvious. But that is neither here nor there. There is no mischievous boy or girl of about fourteen in this case. It is a case of a genuine haunted house, and the haunter is not the child Doris, but one of the devils that enter into empty houses.

"But let us drop the subject for the present, Branscombe," said

Martinus. "We have an engagement to visit Mrs. Temple's home

to-morrow afternoon, and then we shall see what we shall see."

THE HOUSE, which was about ten years old, was a large one, standing in some small grounds, and well set back from the noisy street. A maid in a cap and apron opened the door. The interior showed some standards of taste, and advanced ones of comfort. As we entered we heard a man's high, rather shrill, unpleasant voice in the living-room. Mrs. Temple, who was in conversation with him, appeared embarrassed.

"Doctor Martinus, let me introduce you to Mr. Craven," she said.

Martinus, who had not presented me to Mrs. Temple in his office, did so now, and I was introduced to Craven in turn. He did not impress me favorably. A stout, florid person, apparently in his early forties, in a semi-clerical coat and a clerical collar—pompous, over-fed, and evidently obsessed with the idea of his own importance. He greeted Martinus with a touch of condescension—as a professional might greet an amateur.

"Pleased to meet you, Doctor," he said. "Mrs. Temple has been telling me about your work. Well, we psychie dabblers must stand together, whether inside the church or outside—eh, Doctor?" he chuckled.

Martinus looked at him blankly, but that did not disconcert him. Mrs. Temple intervened tremulously.

"Mr. Craven has been so kind as to promise to cooperate with you, Doctor," she said. "I thought two heads might be better than one if—"

I thought Martinus would explode, but he did nothing of the sort. "I

shall be delighted to have Mr. Craven's cooperation," he said, with

a cynical smile.

"THAT'S FINE!" boomed Craven. "Nothing small about us researchers, is there, Doctor? We can't afford to have any petty jealousy of each other. The subject's too vast."

"Yes—as big as the universe," replied the doctor. "Or, as small as a bath-room," he added, with a meaning glance at me. "Just as we make it, you know, Mr. Craven."

I knew he was thinking of the character in one of Dostoevsky's novels,

“We always imagine eternity as something beyond our conception, something vast, vast! But why must it be vast? Instead of all that, what if it’s one little room, like a bath house in the country, black and grimy and spiders in every corner, and that’s all eternity is? I sometimes fancy it like that.”

--the character Svidrigaïlov, in Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment who spoke of death as a possible imprisonment instead of a release. Craven saw nothing sardonic in the remark.

"Well, have you seen the room since I've altered it again?" he asked. "We might go up, Mrs. Temple? Yes, Doctor, I've put everything back again exactly as it was before. I'm not ashamed to own where I've made a mistake. There's nothing petty about me, Doctor."

It was a pretty little room, overlooking the quarter-acre of back lawn—a room containing a little white bed, with fresh sheets and a white and blue coverlet. A few engravings were on the walls. And the side of the room farthest from the window contained a table on which the child's toys had been set out—everything she had had since babyhood that had survived unbroken.

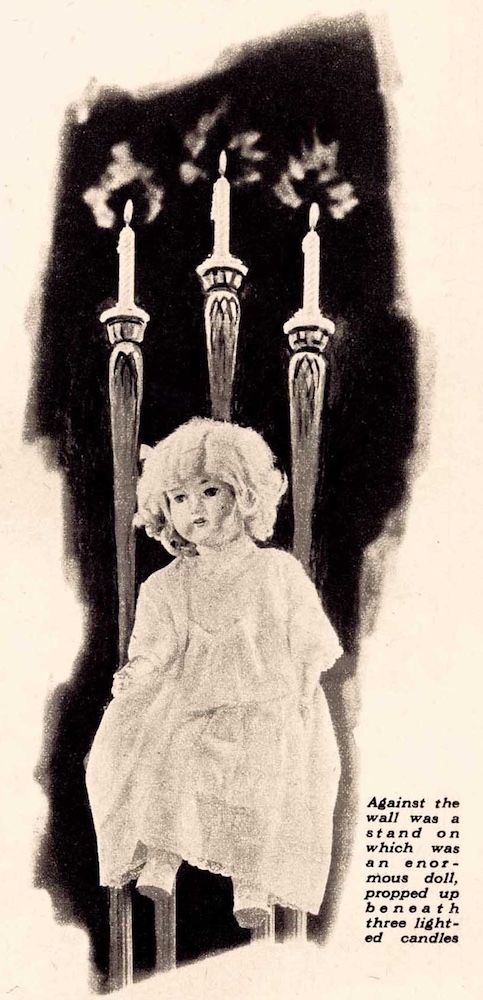

Against the wall was a stand on which was an enormous doll, propped up beneath three lighted candles.

Against the wall was a stand on which was an enormous doll, propped up beneath three lighted candles. An enlarged photograph of little Doris hung on the wall near by, and some fresh-cut flowers were in a tall vase, standing beside the doll.

"So you have put everything back again where it was?" asked Martinus curtly, of Mr. Craven. "The whole epitome of the child's life. May I ask why?"

"Well, you see," replied the fake spiritualist, "I came to the conclusion that the poor earth-bound spirit would continue to haunt this room until things were restored. My deductions had been wrong, but perfectly justifiable."

"And these manifestations have ceased, now that you have pieced together the broken fragments of the vase?" Martinus asked. "You suppose that everything is again—as it was?"

He was, of course, speaking metaphorically, but before Craven could reply there came a sudden crash in the corner of the room. We sprang back—looked around us. A shower of broken glass lay on the carpet. Upon the stand beside the doll, the flowers lay scattered, and water was splashed over the table that contained the toys.

"My God!" whimpered Craven, his teeth chattering. "Who threw that vase?"

"If we knew that," replied Martinus, "we should have gone some distance toward the solution of this problem."

My teeth were chattering. At that moment I was under the singular illusion that the doll's large, blue eyes had taken on an expression of intelligence!

Human eyes? I forced myself to look again. No, of course it had been the way the light had played upon them. They were just a doll's glass eyes.

I was surprised at Martinus's sudden cordiality toward Craven. I had been afraid he would withdraw from the case. Instead, he had cordially welcomed the pseudo spiritualist's cooperation. He had told Mrs. Temple that he proposed to hold a séance at an early date, and suggested that they might all form a circle. On the way back Martinus was silent for a long time—evidently pondering over the case. Then suddenly he began to chuckle.

"You're wondering why I wanted Craven, Branscombe?" he asked me.

"I was surprised," I confessed.

"I have an idea," chuckled the doctor again, "that Craven's presence will prove a powerful attraction to whatever spirit it is that has usurped the child's place in that room. The fool thinks he can tear down the shrine and reconstruct it, just as if nothing had happened, as if no consecration was necessary, as if reassemblage of the physical elements will call back the spirit. As well sew the head on a decapitated man, and expect him to awake to life! A fool like that should prove a powerful drawing-card to the kind of spirit I fancy has come into that room."

"I thought the poltergeist, when not merely an extension of the astral form at maturity, was always an elemental factor," I suggested.

"More or less right, Branscombe. It is a spirit of the lowest order, though it may or may not have once been incarnate. But you must remember I am always urging upon you that these manifestations of the discarnate—throwing of vases, breaking of crockery, and so forth—are merely expressions of energy. It is not to be supposed that the spirit is actually conscious of what it is doing. It lets loose energy in the room, and this energy takes certain forms.

"For instance, a very dear friend of mine once promised his sister he

would try to communicate with her after death. He supposed he had

merely established communication by taps and rappings. He was

heartbroken to learn that he had been pulling down pictures and wrecking the furniture!"

"THEN it may be the child after all?" I suggested.

"Impossible, Branscombe. No child could throw a vase across a room. Remember that before maturity no human being is more than one-tenth incarnate. Little Doris Temple's earthly residence was the merest episode in the life of her spirit. All that remains of her is the happy dream and the memories so rudely shattered when the furniture of that room was shifted. No, Branscombe, it all comes back to Craven's asinine question, Who threw that vase?"

I told Martinus of the expression I had fancied I had seen in the eyes of the doll. He nodded abstractedly, but made no comment.

It was two days later, and before Martinus had had time to go further into the case, that we had a visit from Mrs. Temple again. She appeared in the greatest distress.

"I don't know what I'm going to do, Doctor Martinus," she sobbed,

"—and dear Mr. Craven admits that he is at his wits' end. He was so

sure that dear little Doris would be satisfied when things were put

back as they were, but it's growing worse all the time, and it's not

only in that room now—it's all over the house. My maid has left me."

"WHAT particular manifestations have occurred?" asked Martinus.

"Footsteps up and down the stairs at night—a man's heavy footsteps. Doors opening and slamming. Pictures falling from the wall. And last night, as I lay in bed, I could have sworn I felt fingers about my throat. My maid was pinched black and blue, too. Oh, Doctor, it can't be Doris!"

"No, it's not your little girl," said Martinus. "Have you been dreaming?"

"Dreadful dreams, but I can't remember anything about them, except that—" she hesitated.

"That?" queried the doctor.

"That I had murdered somebody and was going to be executed. But I don't know who it was, or how I was to die." She broke into hysterical weeping.

Martinus made her sit down and mixed some bromide for her. After a little while she grew calmer.

"I am sorry to be so hysterical," she apologized, "but I've gone through so much. What with my little girl and my husband—"

"Tell me about your husband," said the doctor gently.

"Why, it was just at the time Doris lay dying. He was in Texas, and hadn't heard anything about her illness, because he was off with a posse. He sent me some clippings, and that alone would have scared me nearly to death."

"A posse, you say?"

"Yes, Doctor. You remember reading about that man who escaped from the penitentiary, and shot his way clear across three States—James O'Connor?"

The doctor shook his head. But I remembered the affair. O'Connor had been serving a life term for murder. He had broken loose, after killing three guards, and had escaped. At least a dozen of his pursuers had been killed and wounded before the posse surrounded him in his stronghold. There had been summary vengeance taken. The bandit's body was left swinging from a tree, riddled with bullets. I recalled the circumstances.

"My husband was with that posse," said Mrs. Temple. "And he had written me about being summoned by the sheriff, and that—with Doris dying—nearly killed me! I was afraid I should lose both of them. Jim and I have always been devoted to each other, and his absence is unbearable now. He's coming home for good soon, and I'm trying to hold out till then. But after what's been happening"

Martinus patted her arm sympathetically. "I think we shall be able to remedy things, Mrs. Temple," he said. "Suppose we come up to your house to-night. Can Mr. Craven provide a reliable medium for a séance?"

"Oh, yes, there's Mrs. Jimpson. She's wonderful," said Mrs. Temple. "Why, she described my father perfectly, and gave me his name and everything."

"Get her to your house to-night, about nine, then," said Martinus. He turned to me when she had gone. "We can't use any of my mediums on a case like this," he said. "I imagine this Mrs. Jimpson is one of Craven's crowd, and just the kind likely to attract the interest of the late James O'Connor."

"You mean—you think it's O'Connor manifesting in the house?" I exclaimed.

"It's a perfectly good working theory, and decidedly a probability," he answered.

"You see," he explained, as we started for Mrs. Temple's house, if Jim Temple took a prominent part in the lynching of this bandit, it is probable that the fellow passed out with feelings of intense malignancy against him and the rest. When a murderer is hurried into eternity, as you know, he can hardly be said to be dead, in the sense that ordinary people die. Cut off in the full vigor of bodily prowess and activity, he is simply a disembodied entity, just as much attached to the earth life, perpetually rehearsing his crime and the circumstances of his death, and utilizing every opportunity to use other physical mediums for the gratification of his earthly desires and for revenge."

"But why should he have succeeded in molesting Mrs. Temple?" I asked.

"THE FACT that Jim Temple's litle girl passed out almost at the same time as himself established a rapport. There are rapports of hate as well as of love. I have no doubt that, in an obscure way, James O'Connor discovered this means of at once getting into touch with earth life and of obtaining revenge. The emotional condition under which Mrs. Temple was laboring, the fact that her husband had her constantly in his mind—you heard her say they were devoted to each other—established the links in the chain.

"But he found the house occupied. The little spirit of Doris guarded it, and, as love is stronger than hate, he was powerless—'till that fool Craven took the toys away, turned the furniture about, and played havoc generally.

"Then, when Craven re-established the shrine—well, he had re-established a road that was easy following for James O'Connor. But if that Mrs. Jimpson is any good at all we ought to learn something. One word—", he cautioned me. "It would be as well not to allude to our suspicions as to the identity of the poltergeist. If they think it is the child Doris, our friend O'Connor will play up to them, and incidentally play into our hands."

Mrs. Jimpson was awaiting our arrival with Craven when we reached the house. The interior was brilliantly lit with electric bulbs of great power. It was easy to see that Mrs. Temple was afraid of the dark. The child's room, in which the séance was to be held, had been arranged under Craven's instructions. It contained the usual curtain of dark cloth strung across a corner, to form a cabinet, and the half circle of chairs extending from this to the further end of the table that held the toys.

Mrs. Jimpson was a common sort of woman, but manifestly mediumistic. There is something about a genuine medium's eyes that identify her. She went into the cabinet, and passed into trance with the facility of long experience. I imagined that the late James O'Connor would manifest through her, much more readily than the child.

Before Mrs. Jimpson had settled herself, Martinus took the doll from the stand and examined it. It was one of those large "Mamma" dolls, with movable arms and legs, about the size of a three months' child. The doctor handed it to Mrs. Temple.

"Please hold this on your lap and under no circumstances loose your

hold of it during the séance," he told her.

"DOCTOR, do you think this will bring my darling Doris back like she was before?" she asked.

"I think it vital that you should associate yourself with this doll," replied Martinus, in his curt manner.

"What Doctor Martinus means," put in Craven blandly—I could see he did not relish taking a secondary part in the proceedings—"is that the influence of the mother-love will pass into the doll, creating a fetish."

"That's one way of putting it," said the doctor ironically. "Any way, please remember my instructions, Mrs. Temple. And, of course, you understand that the circle is under no circumstances to be broken. Are you ready, Mrs. Jimpson?" He snapped off the electric light.

I heard the medium breathing stertorously within the cabinet. She stirred restlessly. Sighs came from her lips. I felt the tenseness emanating from Mrs. Temple next to me. In the faint light that came through the window I saw the outlines of the large doll she held in her arms. Was it only imagination, or did the thing actually resemble more and more a living child? The stiff body seemed to be growing limp, the head to fall back into the fold of the woman's arm.

Suddenly a whimper broke from Mrs. Temple's lips:

"It—it's moving! It—oh, Doctor Martinus!"

"Hold it!" I heard the doctor whisper in her ear.

"I felt it move. It's too—too horrible!"

"Hold it, as you value your security and your little girl's peace," came back the answer.

She began breathing almost as harshly as the medium, who was keeping up a low moaning sound inside the cabinet. I felt that cold wind that always accompanies such conditions, chilling my fingers. I thought the curtains before the cabinet seemed to bulge outward.

Then I confess my nerves almost gave way as I heard the sudden tiny, piping voice from within the cabinet clearly:

"Mamma!" it cried—just like the "Mamma" doll, but it did not come from the doll—"Mamma!"

I had thought Mrs. Temple a hysterical person, but she kept herself in admirable control.

"Is that you, Doris, my darling?" she whispered, with a quick intake of her breath.

"Mamma, where are you?" the voice piped. "I can't find you. I've been looking for you. I'm all alone."

"Here is your mother, Doris," came the doctor's voice. Then, to Mrs. Temple, "You're not afraid of your own child?"

"No, no! Shall I see her?"

"Not now," the voice piped back. "But I can feel you, Mamma."

A dreadful pause. What was occurring in the darkness? How still it all was! Even the medium had ceased to moan.

"How do you like your baby sister, Doris?" said Martinus softly. I knew, by some sixth instinct, that he was gripping Mrs. Temple's arm to keep her quiet. "Come, don't be afraid, my child. Come and see Mother and her little new baby."

Again that dreadful silence. My hair felt almost as if standing on end. Something was moving near me in the darkness. Suddenly a scream of uncontrollable terror burst from Mrs. Temple's lips.

"That's all!" shouted Martinus. In a moment the room was flooded with the electric light. Mrs. Temple was lying back in her chair in a dead faint, but still gripping the child's doll. And it was just a doll, nothing more.

"Dear little Doris always wanted a baby sister," said Mrs. Temple later. "But why was it necessary to deceive her, Doctor? It seems so dreadful that she should not have recognized the doll she was so fond of."

She had taken quite a little while to recover from the shock. Martinus had insisted on assuming the role of physician, and on Craven's withdrawing. The faker had taken it with a bad grace, and there had been something like a passage at arms between the two men before he withdrew with Mrs. Jimpson.

"My dear Mrs. Temple, if the deception comforted you, surely it was justified," said the doctor glibly.

"But why did she not recognize the doll?"

"Because she had been lost so long. You must remember time does not

pass on the other side as it does with us. It is measured by the intensity of emotion—and for your little Doris years had passed since she visited the shrine you made for her."

I KNEW Martinus was offering explanations that concealed some truth he was unwilling to expound to her. But Mrs. Temple appeared satisfied.

"And you say I must keep the electric light burning there night and day?" she asked.

"Yes, Mrs. Temple. Close to the figure, so that the little spirit may never stray again."

"What a beautiful idea, Doctor!" she exclaimed. "It is like a candle before a shrine—a perpetual candle."

"A good simile," answered the doctor. "So long as the light burns, I do not think you will be troubled with any more manifestations. But—once in a while fuses blow out! We must take no chance of that. Tomorrow purchase some large candles of the kind they use in churches, and keep two perpetually burning in place of the electric light. After a year, it will be only a matter of sentiment. Until a year, at least, has passed, it will be essential to your child's happiness. And"—he rose—"let me beg of you not to let Mr. Craven, or any of your friends, turn you from your purpose."

"Nothing shall turn me from it," she answered solemnly.

DOCTOR Martinus usually explained his methods to me soon after such a case, but it was not until the following evening that he came to me in the little study off his own, where I was preparing his manuscripts.

"Well, Branscombe, you understood, I suppose, just what happened last evening?" he asked me.

"I must confess I was completely baffled," I answered. "I understood it was O'Connor you expected to manifest, not the child."

"That was O'Connor," he answered, in tones that chilled my blood with horror.

"That voice?" I stammered.

"O'Connor masquerading as the child—of whose existence he had become aware. And that was no easy feat in the land beyond death, where matter is so plastic, Branscombe, that it may almost be said, 'wishes are things.' That is the real hell, Branscombe, for souls like O'Connor's—the inability to distinguish reality from the shapes that their desires assume.

"Yet O'Connor had pierced to reality by the force of his will, and that convinced me that we had a subtle and powerful enemy to deal with, bent upon revenge for being hurried out of life by the hangman's noose. He masqueraded as the child, and it was only when I tripped him up by making him think the doll was Doris's sister that I was myself convinced it was O'Connor."

I was thinking of the ghastly horror of the discarnate life, when a doll may be mistaken for a child. What fools these ghosts are, and how true the old race-legends that substantiate this! Martinus read my thoughts.

"You must remember, Branscombe," he said gently, "that the dead can only sense us through the force of emotion. They have not eyes to see, or ears to hear. If the dead man mistook the doll for a child, it was because I had turned his expectations in that direction."

"Well, but—why?" I asked.

Martinus drew up a chair and sat down beside me. "Branscombe," he said, "you are advanced enough to know that the fetish is not a mere block of stone or wood, but actually contains the power ascribed to it, whether from an external source or as the creation of the united aspirations of the worshippers. As our friend Craven said—I did create a fetish. But let us rather call it a 'Luck.' You know Longfellow's poem, The Luck of Edenhall?" he continued impatiently, "how the fortunes of the house were bound up with the existence of the crystal goblet? The drunken heir shatters the goblet, and the foe rush in and put them to the sword."

Yes, I recalled it. "But is that more than a legend?" I asked.

"My dear Branscombe, did you never know any one who kept a queer little manikin on his desk, which he called his mascot?"

I laughed, as he indicated the Billiken The Billiken, "God of things as they ought to be," is a good-luck charm doll created by the Kansas City art teacher and illustrator Florence Pretz, around 1908. Read more at Wikipedia. on my own desk.

"Just why do you keep that, Branscombe?"

"Oh, just for luck," I answered.

"What you have actually done, Branscombe, is to shut up, in that Billiken of yours, all the little bothers and perplexities and gaucheries that you want to rid yourself of—the Russian demon who always reverses your slippers, the little imp who makes you grouchy in the morning, the one that makes you shave too high up on one side of your face, and so on. Well, O'Connor is in that doll!"

I uttered an exclamation of incredulity.

"The practice of burning lights before the images of saints, Branscombe," continued Martinus, "may or may not have been designed to keep them from leaving their habitations. But it is a safe guess that O'Connor will remain immobilized and powerless within the child's doll, just so long as there is a light in front of it. It is just as safe a guess as that you will remain immobilized in your bed to-night, until there is the light of a new day within the room."

"But if this will of his is strong enough to cross that light?" I asked. "Is that impossible?"

"Not impossible, Branscombe," chuckled Martinus, "but—he thinks he

is inhabiting the body of Mrs. Temple's youngest child, and he will

remain there, waiting for it to grow—until he finds that his opportunity has slipped by. After a year or so—a year and a day, according to the conceptions of folk-lore, though there is, of course, no exact period—his power for evil will have dissipated itself, and James O'Connor will be resolved into that limbo where he will expiate his crimes on earth before he gets his new chance in a new body."

I HAVE recorded this case thus far from the notes I took at the time. Martinus had engaged me to keep a record of his cases, and this was one of the many that I attended in his company. The sequel was a telephone call from Mrs. Temple about a week later. She announced that there had been a complete cessation of the hauntings, the candles were burned religiously in front of "dear little Doris's doll," as she termed it, and she did not think it would be necessary to trouble us again.

About two months later I was seated beside Martinus, reading proof for him, when the telephone rang. He picked up the instrument. I recognized Mrs. Temple's voice but I could not hear what she was saying. The doctor listened impatiently, his face showing evidence of extreme displeasure.

"Mrs. Temple, since you have chosen to put yourself in the hands of Mr. Craven again, I feel it is impossible for me to handle the case," I heard him say.

There followed the tones of Mrs. Temple's voice. Martinus frowned and shook his head. "No, it is impossible," he repeated. More colloquy, then a shrug of his shoulders. The doctor capitulated.

"We'll come right up," he said, as he hung up the receiver. He turned to me. "That woman's a type of the eternal feminine," he said. "Her husband's coming home next week, and she doesn't know what to do. It appears that Craven persuaded her once again that the child had become 'earth-bound,' and about a month ago she ceased burning the candles and locked the door. It's been locked ever since. Now Jim Temple's returning, and she doesn't know how she's going to explain things to him. Craven has persuaded her to let him hold a séance with Mrs. Jimpson in that room to-night, but at the last moment her courage has failed and she is begging us to come."

"Have there been any manifestations since she ceased to burn the candles?" I asked.

"Nothing at all. She told me that the first thing. That's what makes me afraid that fool Craven and Mrs. Jimpson are going to set loose forces that will prove absolutely uncontrollable. If that devil can break through to-night—God help Mrs. Temple! Branscombe, I've seen—but never mind what I've seen. We've got to hurry!"

"Doctor," I asked, as we started, "suppose that doll had been thrown in the Harlem River?"

"Then, Branscombe, O'Connor would have had full play for his devilish impulses. To-night he must be sent back where he comes from—if we can do it."

THE SÉANCE was just beginning , when we arrived. Mrs. Temple did not seem to want to open the door for us. It was clear enough that, in spite of the moment of reaction from Craven's influence, during which she had telephoned the doctor, she had fallen entirely under the faker's control. She announced, with a nervous laugh, that there was to be no séance after all—denied that Craven and Mrs. Jimpson were in the house, until his voice came booming down the stairs, inquiring whether it was us. The doctor simply strode past Mrs. Temple and went upstairs. I followed him, and she came up behind, still protesting.

The room was lighted, but there was no light before the doll, and everything was covered with dust. Mrs. Jimpson was just settling herself in the cabinet. Craven tried to bar our way.

"This is an outrage, Doctor Martinus!" he shouted. "We are here by Mrs. Temple's invitation," answered the doctor quietly. "We intend to remain."

Mrs. Temple weakened. "I don't know what to do," she fretted. "One advises me one thing, and one another. I only want my darling little girl to be happy."

"Doctor, if you had the most elementary knowledge of psychic matters, you would know that every effort to attach the spirit to earth draws it from its heavenly reward," Craven exclaimed. "It was on my advice that Mrs. Temple let those candles burn themselves out a month ago. There have been no manifestations since, proving that the child no longer haunts this house. To-night we propose to hold a séance to determine that all is well with her, after which we shall leave the pure spirit to enjoy its well-earned rest."

"Go ahead," said Martinus. "There will be no interference from either of us. But we propose to be present as spectators. You may be glad of it before the séance ends, Mr. Craven."

"If Doctor Martinus and Mr. Branscombe will pledge themselves not to interfere, I am sure you will not object to their staying, Mr. Craven?" asked Mrs. Temple.

Craven sulkily agreed.

AGAIN we took our seats, and the light was turned off. The medium began to struggle and moan. And this time I was conscious of a presence, indescribably evil, in that room. It was like physical contact with something too loathsome to have human form. I shuddered, I felt nauseated; it was all I could do to keep my place in the half-circle. I wondered if the others felt the same. All the while, too, it seemed as if I was resisting some physical pressure, bent on crowding me out. I strained against the chair—heard myself breathing hurriedly—felt the surge of the blood through my body.

It came: "Mamma! Mammal" piping out of the cabinet.

"Doris? Darling little Doris, Mother is here. Are you happy, Doris?"

I heard the Doctor catch at his breath, as if about to speak—then he seemed to think better of it. I saw him outlined tensely against the faint light of the window-square.

"Daddy! I want my Daddy!" came the baby voice.

"Daddy is here," boomed Craven.

Now what induced the man to utter that lie is more than either Martinus or I could figure afterward. There followed a tense silence. Then that evil power within the room seemed to dominate, to overwhelm me. My brain reeled. I was choking for breath.

A peal of maniacal laughter rang through the silence. And I knew there was a body there—some vast, inchoate, evil thing that seemed to fill the room.

A chair fell over. The thing laughed again, and mingled with it came Mrs. Temple's scream, and a sound from Craven's throat that I cannot possibly describe. It was a cry, but a cry that seemed the embodiment of utter despair—the cry of dissolution.

Then—a heavy body toppling to the floor, and threshing it with its heels.

"The light, the light, Branscombe, for God's sake!" I heard Martinus calling, but as if from far away.

We were both groping for the button. We struck our heads together in the dark, fumbled in the dark, and at last, somehow, got the light turned on.

The medium was stirring in the cabinet. Mrs. Temple was seated rigid in her chair, staring in front of her, and muttering. The light of reason was gone from her eyes. On the floor lay Craven, apparently hugging to his heart the "Mamma" doll, with frantic grip.

But as we bent over him I saw that the little porcelain fingers were fixed in his throat like steel hooks, so deep that the swelling flesh was already closing over the arms.

Craven was dead. The fingers of the doll had stopped the circulation in the carotids completely. Death had been a matter of perhaps fifteen seconds.

THE REST is happier than either of us had hoped. Thanks to Martinus's care, and certain suggestions made when Mrs. Temple was in a condition of hypnosis, and before she had recovered her reason, she awakened with no recollection of that final scene in the drama. Had she remembered, Martinus told me, reason would never have returned.

She was told that Craven had collapsed and died of heart disease at the beginning of the séance, and this was believed by Mrs. Jimpson, who was still in trance at the time of Craven's death. It was a comparatively simple matter for Martinus to issue a death certificate to this effect, and so hush up the facts.

Jim Temple returned to a house, swept and garnished, but this time without a devil in possession. The impulse that had enabled the dead bandit to wreak his revenge upon the living had been exhausted by that act, and James O'Connor was carried far beyond the sphere of earthly passions. The Doctor burned the doll in his fireplace when we got home that night.

"But the child—Doris?" I asked him. "Where was she while O'Connor was masquerading in her place?"

"Don't let us worry about her, Branscombe," answered Martinus. "It's a safe bet that there is provision on the other side to protect the Dorises against the James O'Connors."

Then I added: "In any case, you and I have done our part."

Part of the series Dr. Martinus, Occultist

Illustrations from Ghost Stories Magazine, January 1927