Remarkable achievements of Ivan Brodsky, physician, whose investigations into psychic phenomena enabled him to cure spiritual diseases and to exorcise evil spirits from the bodies of their victims.

THE adventures which I encountered in the company of Dr. Ivan Brodsky, while assisting him in his psychical experiments, had all, as I have hitherto related them, arisen out of his earnest desire to aid his fellow men. I have now to record one of a different character, in which the doctor for the first time broke his self-imposed rule not to tamper with psychical affairs out of curiosity or scientific interest. It was—on this ground, perhaps—a failure, so far as ultimate results are concerned; yet it was of so strange a character that I feel it is worthy of record.

One evening when I entered the doctor's apartment I found him curled up in an arm-chair, surrounded by a pile of dusty tomes, some apparantly of a most venerable age. As I entered he looked up at me rather searchingly.

"Have you ever heard the legend of Friar Bacon's head?" he asked.

I happened to recollect that absurd story, and told him so. How the learned Friar had succeeded in making a brazen head that spoke to him and answered questions; how it finally grew sullen and refused to answer him; and how the Friar, overcome with rage, seized a hammer and shattered it to pieces.

"There is a similar legend in the Talmud," said Brodsky, when I had concluded. "A learned rabbi, skilled in the Kabbala, succeeded in making a little man, a humunculus, to do his bidding. For the six days of the week it toiled for him, going about the house mechanically, sweeping, dusting and cooking. Then came the seventh day, on which it was forbidden to do any manner of work. Forgetful of this, the rabbi went off to the synagogue, and, while he was there, his pupil rushed in in a condition of high excitement. 'Master! Master!' he cried, the man that thou hast made has run out into the street and is knocking down the people.'

"And yet," mused the doctor, "why should it not be possible to create life, since soul is everywhere diffused throughout all visible things?"

Just then the front door bell rang loudly and Brodsky gathered up his books.

"At any rate," he said, "I want you to meet Professor Adams, the great Egyptologist, who is now arriving. We have some such experiment in view, and you shall hear what he has to say."

Professor Adams

A moment later the professor joined us. I had heard of him by reputation as one of the most daring constructive historians of ancient Egypt, who had won the hatred of the conservative school! by the verification of his brilliant hypotheses concerning Egyptian art, religion and morals. The man I now saw confirmed the opinions I had formed of him. He was some sixty years of age, his head was bald, save for a fringe of iron-gray hair, his face was deeply lined; yet there was the light of an enthusiastic soul in his eyes. The man might have been pontiff of the Inquisition: I felt instinctively that science was his god, that he would shrink from nothing to attain knowledge.

"Now, my dear professor," said Brodsky, when he had introduced us,"I think you had better tell my secretary yourself about our projected experiment."

"He is trustworthy?" asked the professor cooly, bending a pair of brillant black eyes upon me. "Not bound by prejudices?"

"Indeed not," the doctor returned, laughing.

"When shall we attain an emancipated age." said Professor Adams with a sigh. "When will men seek truth and be content to follow wherever she may lead them? Today free thought hardly exists. You, my dear Brodsky, have discovered spiritual laws of the utmost consequence to humanity. Yet, if you were to publish these you would be called a madman; even our brethren would cry you down. Why? Simply because they are bound down by their own misconceptions; their minds are not flexible. You vouch for our friend's character?" he continued, smiling.

"Absolutely," returned the doctor.

"Then I will tell you our plans," said Adams to me. You may possibly know that I am the most intelligent and skillful Egyptologist in this country or any other." He paused and looked at me searchingly. "He thinks me boastful!" he cried to Brodsky. "There he goes; conventional prejudice dictates that a man must not tell the truth about himself, and already our friend's mind is fermenting with misdirected zeal——"

"On the contrary, professor," said I. "I know that what you say is correct."

"Good!" cried Professor Adams. "Well, I was about to add that, much as we know about ancient Egypt, what we do not know is infinitely greater. How often have I walked throug my mummy gallery—fine fellows they are, lying in their handsome cases—and said to them, 'You, Nebo Nebo could be a name associated with the Babylonian god of literacy, but in this context I think he might be Pharoah Necho II, who is mentioned in the Old Testament, though not, apparently, in the same books as Joseph. there! You must have been contemporary with Joseph. Come back to life and tell me about his corner in grain.' 'You, my friend Sesostris, who wear your hair after the style of the Ptolemies, did you ever see Cleopatra, and was there really anything between her and Mark Anthony, or did some writer spread that lie among the Romans?" And that is about as far as I got until I made the astonishing discovery that neither friend Nebo nor friend Sesostris Sesostris: Egyptian king mentioned by Herodotus, in his Histories. Stories about him are likely based on the lives of multiple historical pharoahs. (Wikipedia) had ever been embalmed!"

I was so fascinated by the professor's breezy speech that I hardly grasped the significance of this fact at first.

"In other words," said Adams, "their bodies, though shriveled and almost fossilized with age, were preserved intact by reason of certain herbs placed in their wrappings. Every organ remains intact. Every ordan remains intact. Now, sir, if these dried frames were brought back to a semblance of life by saline injections into the veins, we should see Nebo and Sesotris as they appeared in life."

"About the time that I made this discovery I bevan thinking of our friend Brodsky here. The universe, he told me, was a mass of discarnate soul stuff. Why, if three persons sitting at a table in a dark room can make even the wooden table live, would it not be possible to animate real flesh and blood?"

"Emphatically possible," said Brodsky. "But unfortunately we could not be sure that the sould of either Nebo or Sesostris would be the one that returned to its habitation. As for Nebo, he lived so long ago that he has probably been incarnated at leaSt once since his death, and is, in consequence, too far removed from his ancient Egyptian life. Sesostris may not have returned, though fifteen hundred years is usually the longest period between rebirths. In such event he might still retain some memories of his old life."

"Let it be Sesostris, then," said the professor. "Then you will come to my house in Baltimore on Thursday evening and attempt to bring back the personality of our Egyptian frind?" he queried impatiently.

The doctor hesitated.

"Professor," he said candidly, "if any but you asked me to do this I would refuse. I gave you my qualified assent solely because of your long work and your researches. Yes, I will come, but you must promise me that if I recall the spirit for one short hour you will never attempt the experiment again."

"I promise gladly," Professor Adams returned. "Why, an hour will be ample. I only want to ask a few questions—whether the Ptolemy Philopator we read of was the son or nephew of Agrippina the wife of Thoth; whether the Egyptian masses ever adopted the Roman toga; whether the gold ring remained the badge of nobility after the assassination of Caesar; whether the old dam at Thebes had yet been built; the exact dimensions of the colossal lighthouse at Alexandria and the length of the Delta in Cleopatra's time; with a few elucidations on the statement made by Herodotus concerning the migration of cranes; and—"

"I am afraid, professor," returned Brodsky, "that you will find your own knowledge of ancient Egypt considerably exceeds that of your friend Sesostris. However, I will do my best. We will be at your house in Baltimore on Thursday evening and will ask you to be alone and to await us in your mummy gallery."

I pass over the intervening days, which I spent in a fever of anticipation. Could Brodsky really restore life to a mummy, reconstruct the days of Caesar and Ptolemy, so that time would be virtually annihilated? If so, he was an incomparably greated magician than I had ever believed him to be. But I said nothing to him, and he did not volunteer any further statement. At last the time arrived when we were ushered into the enormous house which Professor Adams occupied in a residential district in Baltimore. It stood by itself in some extensive grounds. Adams opened the door himself, for he had sent away his servants, in accordance with the doctor's mandate. He led us into a long hall, down either side of which ran winged figures, bulls with kings' heads, from Assyria, obelisks covered with inscriptions, and, here and there, some upright mummy case, beautifully carved. The air was redolent with spices.

But what attracted and facinated me was a long table in the center of the hall. It was not unlike a billiard table, in appearance, except that the top was level with its edges. It's surface was composed of slate, and it had been set level with scrupulous care, as was evidenced by the little bead within the spirit level, that stood precisely in the center of the glass tube. Upon this was a magnificent mummy case, into each end of which had been fitted a very modern handle of brass

"Now, sir," said the professor to Brodsky, "if you will stand at this end and take the handle I will show you our friend Sesostris."

The two men took their positions, the one at the head, the other at the foot of the case, and, with some difficulty, they raised the lid. I started forward, but remained rooted to the spot in astonishment, not unmixed with admiration.

Within the case, lying as though asleep, was the mummy of a man. Mummy, I say; and yet, save for the parchment-like appearance of the skin, which clung tightly to the bones, and the absence of the tissue, one might have thought that he slept. The eyes, closed, were beautifully fringed with long lashes; the hair, black and curling, thickly covered the skull; there even seemed a tinge of color in the olive cheeks.

"Ha! You are amazed!" said the professor. "Yet—is this a miracle? Why, have you not seen the dried prune swell out to life and beauty when steeped in water? So here, by the injection of the saline mixture, containing some of the red coloring matter of the blood, which synthetical chemistry can easily create, into the veins and arteries, I have restored Sesostris to something of his appear ance nineteen hundred odd years ago. A handsome fellow! See the thin lips, the curved nose, the character in the face. Prop him up, so. Now, doctor, the rest remains with you."

"We must have total darkness," said the doctor. "As you know, such manifestations cannot take place in any degree of light, since the vital processes occur in the dark and develop there, just as the seed that matures under the ground."

"You—you really think that you can bring him to life for an hour?" asked Adams, rubbing his hands.

A shade of vexation crossed Brodsky's face.

"I believe," he replied, "that for the space of one hour I can induce some discarnate intelligence to occupy this shell. Whether it will be that of Sesostris, I cannot tell. Let us hope so. And now kindly draw up chairs around this table; I will sit at the head, and you will sit on either side of the mummy, joining hands across it. Professor, we are waiting for you."

Professor Adams went the length of the hall, snapping out the electric lights. I confess that a certain eerie sensation, not wholly dissociable from fear, crept over me as the shadows lengthened and the long outlines of the mummy cases, the obelisks, and the winged bulls, were thrown into blackness. Over our beads one single light remained. Adams snapped it out, sat down, and stretched his hands to mine over the mummy in the darkness.

There we three sat in perfect silence. I hardly dared to breathe in the thick, spice-scented air. I was painfully conscious of every vital process: the heart. pumping blood laboredly to the extremities; the lungs, automatically taking in their fill of air. Across the table I heard Adams gasp and wheeze. Then I heard Brodsky's low voice.

"Breathe away!" he said softly. "It is a good sign. To create this life it is essential that each of us contribute a certain quantity of his own vitality. Do not be alarmed at any thing you see or hear. Breathe softly and concentrate your minds upon the task in hand."

Still we sat there. Cold spasms of fear overcame me; I felt as though my dissolution were approaching and beads of sweat, icy as death, sprang out upon my forehead. I felt the professor's hand tremble in mine.

Then I heard the faintest rustle in the darkness. I heard something that scratched, something like the faint gasp of a living thing. An icy wind arose and came whistling down the long hall, wailing and whining round the obelisks. It swirled over the table. My brain swam, my senses failed me. I could no longer feel the professor's hand in mine. I tried to rise, to cry out, but even the powers of locomotion had left me. And on the table once more that scratching sound arose. It was like nothing that I had ever heard in life. In my horror I could imagine only one simile for it—the scratching and tapping of a chick, trying to break through the shell of the egg.

And suddenly, out of the darkness, I heard a feeble wail—the wail of a new-born child. I heard the doctor spring to his feet, and an instant later he had switched on the electric light above our heads, while the long shadows of the statues and obelisks rushed out toward us from the sides of the hall. Then the cry changed into a deeper roar, and I saw that the thing upon the table moved.

I think the surprise of what we saw threw us all off our balance more or less, including the doctor. For in place of the full grown man coming back to life after his long sleep, dazed, perhaps, perplexed and confused, but still manifesting the energies of his kind, there was a man-babe—a man in stature, but helpless as though newly born. The cry had changed to the harsh bass of a man's vocal chords. But the eyes, as though they had opened for the first time upon the light, stared and winked meaninglessly, and there was no power of coordination in the muscles of the limbs, that moved senselessly, while the hands, doubled and clenched as a baby's, stretched out toward the electric bulb, as though striving to take hold of it. We three stood, staring and helpless, at the thing that we had made.

I do not know how long we stood there; so long that the monotony of the cry had paralyzed our sense of hearing. I think it was its sudden cessation that released us all from the spell which held us. Then I whispered to Brodsky:

"It is learning!"

For some sense of coordination was coming into the limbs. The creature raised itself upon its elbows, it foundered helplessly, something in the manner of a fish flung upon a bank; and suddenly it toppled out of the case and rolled on the table, balanced for a moment on the edge of the slate, and fell to the ground. Then, with its newly developed sense of locomotion, it crawled, infant-like, until it clutched at the professor's knees, raised itself, and stood upright for the first time, gripping the edge of the table. And it looked upon us vacantly, yet with an ever-dawning intelligence in its eyes.

I cannot describe in detail the stages of that awful evolution. We appeared destined to behold, in that one hour, the unfolding of a complete cycle of human life. Time was, as it were, suspended for us; or rather it spun forward with frenzied swiftness, so that we actually seemed to pass through a span of human existence there. The creature released its hold of the table after a while, stood up erect, as tall as the doctor, and began stumbling forward along the floor, swaying from side to side. It had reached the age of childhood now; infancy was behind it, and it was time for the appearance of the normal psychological instincts of affection.

We saw the light of intelligence come into its eyes as it turned them on us and gazed on us, puzzled, apparently, and uncertain, as some house pet that sees its image for the first time in a glass. But it manifested none of the child's affection for its parents. It seemed to divine, by some horrible intuition, the awful circumstances of its birth. It shrunk back, retreated into a corner of the hall, and crouched there, glaring and gibbering at us. As it swayed uncertaintly from side to side it stumbled over the projecteing edge of a mummy case and fell. It leaped to its feet with a shrill scream of pain and fell upon the inanimate wood, reducing it to splinters with a few well-directed blows of its naked fists. And how it had learned the secret of its strength. It came out of its corner, its eyes fixed savegely upon the doctor's.

"Take care!" I screamed.

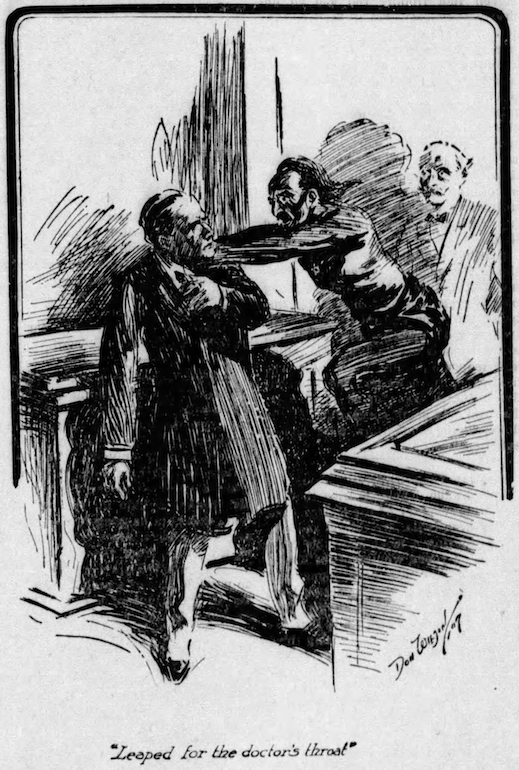

Leaped for the doctor's throat

I was too late. With the cunning of a cat it had crouched down, it averted its gaze one moment; then, straight as an arrow, it leaped for the doctor's throat, seeking, with the wild beast's instinct, for the great vulnerable arteries. Brodsky staggered under the impetus of the attack; I glanced hastily round me and perceived an instrument of iron with a long handle of wood, such as is used for opening packing cases. I flung myself upon the thing and belabored it with all my strength. It left the doctor and turned upon me, snarling. I hit it with all my force upon the bridge of the nose, and with a whine it fell at my feet, fawning upon me. It had discovered the meaning of its second lesson, the strength of others. Brodsky rose slowly. His shoulder had been bruised, but he was not otherwise injured.

We three withdrew into a corner of the room and watched the creature. The fight had been beaten out of it; with the short memory of the savage it seemed already to have forgotten its sudden murderous onslaught. It was now crouched upon the floor, fingering the tool which I had let fall, patting and turning it over with an aspect of intense curiosity. This was the stage of prehistoric man, the separation from the beast by the faculty of imagination.

Professor Adams found his voice. "This is terrible, doctor," he whispered tremulously, plucking at Brodsky's sleeve. "What will you do with it? I have some chloroform in my room; I keep it for cleaning the papyrus. Shall I bring it in? You can destroy—"

It is not necessary," I answered. "Look!"

They glanced back at the creature. It was still seated upon the floor, but had dropped the tool and now sat, crouched in a heap, staring before it idly, while a low whimpering sound came from between its lips. And its aspect had changed. With the arrival of adolescence the features had insensibly altered; already I had noticed how the soul within, working upon the plastic clay, moulding it in its own image, had thrown back the fine forehead of the mummy, enlarged the jaws, lengthened the arms and bowed the lower limbs, until it began to show the semi-human appearance of primeval man. But not the muscles had wasted upon the limbs, the face was lined, the thick growth of beard that had sprung out upon the lower half of the face was turning white. The creature was aging visibly before our eyes. Its span of normal life was almost over.

And then occurred the most pathetic of all the incidents that I remember. Perhaps primitive man feeling his strength go from him, might have wondered in his dimly developed mind at the slow approach of death, pondered upon the unknown gulf before him, toward whose edge he was approaching with irresistible movements and longed that his little, helpless life should not go out alone, without some human companionship. The creature half rose, and, very bent and faltering, stumbled toward us and cowered at out feet, laying its head down upon the ground before the doctor, much as an old dog might seek its master in the hour of death. In spite of my repugnance, tears sprung into my eyes. This was our first ancestor, the father of the race. Brodsky stopped over the thing and laid his hand upon its head. The head was raised one instant; I saw an agony of question in the eyes. Then the body collapsed, it moved faintly once or twice, and a long sigh shook the frame. A moment afterward it began to grow cold. I turned it upon its back. The face was that of an old savage in the last extremity of old age.

Then the body collapsed

We placed the body back in the case and left it with Professor Adams. Then we departed. We did not know whether hours or days had passed, whether it were night or morning. But the streets were still dark; and when the doctor pulled out his watch we saw that it lacked an hour of midnight. Only two hours had passed since we first entered Adam's house; but they were the longest I had ever passed. Neither of us spoke that night as the express train whirled us back to our home. But in the morning, when we were back in the doctor's study, he voluntarily brought up the subject.

"I need hardly say that the creature which came into the mummy's form was not that of Sorostris," he said, quietly. "Perhaps the influence of that place, which was nothing but a graveyard of the earliest civilized men, attracted some primeval savage that had passed out of this life when human consciousness had hardly risen above that of the brute, and who had, in consequence, lingered in a semi-conscious state until we involuntarily gave him the impetus toward further development. As for that 'crowded hour of life,' we simply omitted to take provision against the fourth dimension."

"The fourth dimension?" I cried.

"The fourth dimensional existence in which time is not known," the doctor answered. "Time is, of course, a human limitation, and was not known to the earliest savages, any more than it is recognized, in their wild state, by animals. Everything that has ever happened, is happening now, or will happen in future, takes place simultaneously."

"You mean that I am at once a child, a man, and a dotard, as the creature was?" I asked. "That Caesar and Washington were and are contemporaries? That we are living both in the glacial epoch and in our own?"

"Exactly," the doctor answered. "Instead of time passing by us, we travel through time, much as, although we in the carriage think the fields are passing us, it is, in reality, we who are passing them. The matter is a little dificult to explain, but, let me offer you an analogy. Picture human life as a snake that wriggles past a certain point of vision. It appears out of the unknown, crawls along the ground, and disappears, no one knows whither, leaving nothing to mark its course except its trail in the dust But, because we see it no longer, that does not prove that it has ceased to exist, or that it is not contemporaneous with other snakes that crawled past yesterday, or may crawl past in future. So with our savage. He came from the unknown and disappeared; he changed from youth to age, as the snake changes from head to tail, tapering away into nothingness. Yet let us take comfort in the thought that even as with Sesostris, with you and with me, no human life is purposeless and if we cannot understand the final ccause of things we know that all will be well with us."

Part of the series Ivan Brodsky, Surgeon of Souls

Original copyright 1909, W.G. Chapman, Great Britain.

All illustrations from Stevens Point Journal Feb. 3, 1911. Source: Internet Archive

Artist's name appears to be Don Weigon, illustrations apparently dated 1909.

Annotations by Nina Zumel