Professor Garretson was a man of about fifty-five. His face was intellectual and stamped with a certain austere power; yet it also impressed me as that of an imaginative man, a dreamer who has missed making his mark in life because he held his judgment in abeyance while pondering the emotional values. And this diagnosis was entirely correct. For thirty years he had held the chair of classical languages at Maryland University, and was now retired upon a comfortable pension. He was visiting a New York friend on the eve of sending his ward, Margaret Lassalle, off to Europe.

"They are not intellectual processes but matters of spiritual recognition."

Miss Lassalle was twenty—a quiet, thoughtful girl, strikingly like her guardian in temperament. If he had been younger and she older theirs would have been, I thought, an ideal union. The professor had adopted her on the death of her mother when she was a baby, and the affection between them was a very close one.

I met them at Doctor Immanuel's apartments in New York. Miss Lassalle was to sail for England two days later, and they had come to pay a visit to the Greek physician, who was an intimate friend by correspondence—that is to say, Phileas Immanuel and Arthur Garretson, though this was only their second meeting, had both been prominent members of the Archaeological society at Athens, which is, as most people know, largely an American enterprise.

The strange couple did not stay long after my arrival. When they had gone and we three were left alone—Immanuel, I, and Paul Tarrant, the rich man whose monograph upon Assyrian coins will, I fancy, last longer than his banking house—the doctor spoke of them.

"Garretson is one of my oldest friends," he said. "We have corresponded for years, although we never met until last week. Did you notice the curious attachment between him and his ward?"

We had both noticed it.

"You would think a well-to-do bachelor like that would try to marry her," suggested Tarrant.

"On the contrary," answered the doctor, "Garretson is sending her to Europe precisely to avoid that eventuality. You know he has made a sort of father confessor of me during our long epistolary acquaintance. I suppose he thought that we should never meet and that he could better unburden himself to a stranger. He is quite desperately in love with her, and I fancy she cares a good deal for him. But he realizes the difference in their ages—and there is a young man in England to whom, he fancies, Miss Margaret is not indifferent. So he is going to send her there for a couple of years, ostensibly to study music, but really, I think, in the hope of her happy marriage. And the poor fellow is broken-hearted."

He paused, and suddenly I knew that there was more—a great deal more—to the story.

"And yet," he added, "if both only knew that each is destined for the other, that unless they recognize each other they will suffer through many lives to come—"

Tarrant always came to the point bluntly. "I see," he began, "that this is another reincarnation story. When did they love last? In Greece, Assyria, Rome, Siberia, or in uttermost Tartary?"

"Thirty-five years ago," answered the doctor.

"Fifteen years before the girl was born?" cried Tarrant.

"Exactly. This story does not deal with their incarnation either in Greece or Rome, although I do not doubt that they were lovers then. I know his history from friends and have pieced it together. Shall I tell you, gentlemen?"

"Why didn't you tell him?" asked the millionaire.

"Because," answered Immanuel, "these things cannot be forced; they are not intellectual processes but matters of spiritual recognition. You don't care to hear, though?" he added. a little huffily.

"Yes, indeed," cried Tarrant apologetically. "Pray go on, doctor. But I may ask questions?"

"A hundred," answered Immanuel, smiling. "Did you ever hear of Pelorus Jack?" Pelorus Jack was a Risso's dolphin famous for meeting and escorting ships through the narrow and dangerous channel known as French Pass, in New Zealand. He guided ships for 24 years, from 1888 until he disappeared in 1912. He was the first individual sea creature to be protected by law in any country. (Wikipedia ) he said abruptly.

"You mean Jack Pelorus?"

"No, Paul; and now I am dealing with a matter of record, for you will find a reference to him in the laws of the Austrian commonwealth. Pelorus Jack is a dolphin, and the only dolphin who is strictly protected by statute during all seasons of the year."

The famous dolphin, Pelorus Jack

"He must be a remarkable fish," said Tarrant.

"He is," snapped Immanuel. "He is supposed by the sailors to be the reincarnation of a French fisherman who died not long ago in an Australian coast city." For an alternate theory, see Legends of Pelorus Jack.

"Question Number One," said Tarrant. "Do you mean to say that men are reborn as fishes, or animals?"

"You have anticipated my argument, Paul," the doctor answered. "Under almost all circumstances—no. Yet, though almost universally, when once we become human, the smaller doors are shut behind us, sometimes we do become 'entangled,' as the Indian scriptures phrase it. That is to say, if the desire for reincarnation is so intense that it transcends the mechanical possibilities, the discarnate soul may return to birth, using the limited medium at its possession, either as a beast or as a plant. You will find it distinctly stated in the Brahminical books that the departed soul descends first into plants."

"Plants!" shouted Tarrant. "You mean that I shall come back as a geranium?"

"No, my dear fellow," answered Immanuel, smiling. "I mean that the body-making potentialities may first be concentrated and focussed, so to speak, in some plant medium—for a while. Have you never heard of the dryads, the Greek spirits of the trees?"

"It strikes me," I suggested, "that we are getting off the track. Suppose we return, first to Pelorus Jack, and then to the professor."

"Pelorus Jack—yes. Well, he was simply a dolphin who formed the agreeable habit of meeting all incoming ocean steamships and piloting them into the harbor of Melbourne—was it Sydney? Anyway, he became so famous and popular that the commonwealth government made it a crime to kill him. And, until within the last year or so he was a constant feature of interest to the passengers. But I instanced him as an example of a soul becoming entangled in animal form. Now I will hark back to Professor Garretson.

"Thirty-five years ago Andrew Garretson, then a young man of twenty, came to this country from Scotland and settled in Prince George County, Maryland. He was a well-to-do youth, his father having recently died and left him, the only child, a modest annual competence. I believe his purpose in leaving Scotland was to escape the memories of some boyish love affair. Whatever it was, it was nothing lasting, although at the time he probably thought that it was. You see, even in those days he was susceptible—just a shy, bright, affectionate lad who picked out Maryland of all places in the world, as he thought by a whim, but really because he was controlled by far-reaching purposes.

"Mary Lassalle was the only daughter of one of the professors at the university. Lassalle, meeting Garretson, took a fancy to him, and after some thought the young Scotchman, who was of a studious disposition, determined to enroll at the university, and endeavor to become one of the faculty after his graduation. That was the sort of quiet life that appealed to him—and he has never had reason to regret his decision.

"The two young people fell madly in love with each other. It was one of those romantic attachments rare in that day and time, though not so rare as now. There was a sort of spiritual bond between them which made each almost a portion of the other; it was almost as though the same soul animated both bodies. So unworldly was their love that the thought of marriage was looked upon by both only as something ultimate and remote. Professor Lassalle and his wife looked favorably upon the engagement; it was arranged that the young people should be married as soon as Garretson completed his course and obtained the position which would obviously lie open to one of his talent. As you may know, he is one of the few classicists in America of world-wide reputation.

"The year 1880 was one remarkable for many things. Among these was the spiritualist craze, which was running through America like a fire. True, it was long before this that the Fox sisters had laid the foundations of the modern Spiritualist cult at Rochester; but in the late seventies there was a remarkable recrudescence of this superstition. Impudent 'mediums' imposed upon the gullible all through the large and small cities of the country—they do yet, I am told, but then the imposture was comparatively new. It did not pass over even the quiet little home of the Lassalles, where Garretson boarded. The two elders and the young people often sat round the table and 'laid on hands' with the usual obtaining of amusing and impossible communications. We know now that these forces are nothing but thought impressions, either of the sitters or of others, cast off and congealing round this magnetic nucleus—mere rubbish from the world's psychic waste-baskets, so to say. But to the young people all this was very real. They lived in a world peopled with invisible intelligence, and to them death was nothing more than a simple transition from one condition to another, hardly different.

" 'If I should die before you, Andrew,' said Mary Lassalle, 'I shall come back to you. I shall never go far from you, beloved, not for a moment, till, you rejoin me.'

"Andrew Garretson always remembered that evening, for on the next day Mary was taken ill with congestion of the lungs. She never recovered. The chill settled deep into her system; tuberculosis, the dread disease of that period, supervened. In vain they closed the windows and condemned her to a single, unventilated room. She grew rapidly worse and died less than three months after the onset of the disease—died with her hands in Garretson's, and her head on his breast, and her eyes turned up to his in confidence of the continuance of their love through all mortal changes.

"For weeks after the funeral Andrew Garretson was out of his mind. When at last the loving nursing of Mrs. Lassalle brought him hack to health, he took up his life with the profound conviction that Mary was ever with him, watching over him. Sometimes those three would sit at the table and try to obtain messages from her. But though the usual phenomena occurred, even to their minds it became obvious that Mary was not there, that some lying or evil intelligences controlled the tilts. At last by tacit consent these sittings were abandoned.

"There never were such flowers as grew in the Lassalles' garden that first summer after Mary's death. And their peach orchard, which had never done well, now blossomed out into a marvel of beauty. Deep, wine-red blossoms covered the young shoots, and after a while it seemed as though the strength of the flowers was all concentrated in these peach trees. People came from far and near to look at them. And the next year it was the same. Andrew Garretson, now one of the faculty, obtained the reputation of one who could make anything grow for him."

Vincent Van Gough, Pink Peach Trees (Souvenir de Mauve) (1888).

"It's quite common," I interposed. "I've often heard people say that flowers will not grow for them, while others can charm them and have wonderful gardens."

Doctor Immanuel shot a quick glance at me. "Yes," he answered. "Flowers are quite conscious of the personality of those who tend them. But perhaps the most astonishing thing, and one which puzzled experts from various botanical stations, was that, in his presence, the plants actually lost the heliotropic faculty."

"What on earth's that, doctor?" asked Tarrant.

"The faculty of turning toward the sun. Plants in window boxes, you may have noticed, invariably turn their backs disdainfully upon their possessors, and point outward toward the light. Yet it was affirmed that Garretson's window plants pointed inward. However, whether this were the case or not, I spoke of the peach orchard, in which all the power that he evoked seemed to be centered.

"So the years rolled on. Garretson was now thirty-five. His fiancee, had she lived, would have been over thirty. Mrs. Lasalle had died two years previously, and the old professor, who mourned her loss desperately and could not be comforted, suddenly endeavored to find happiness in life by marrying again. Until this time Garretson had lived with the Lassalles—that is to say till the lady's death, and afterward with Lassalle alone. The advent of the new mistress changed all that. Naturally a woman does not want her husband's friend, and a prosy fellow at that, as a perpetual boarder. Added to which, the new Mrs. Lassalle conceived a distinct aversion to Garretson. So he moved out of the house, and about this time Lassalle, being superannuated, retired with his wife to a little country home some twenty miles away. So the long friendship was broken up. Garretson boarded a few blocks distant from the old house and lived almost a recluse, his only memories those of Mary Lassalle, his only hopes of meeting her again. The new owner of the Lassalle home, pitying the forlorn man, suggested that he should continue to take care of the garden, and to this proposition Garretson gladly assented.

"Then, very suddenly, a strange, event occurred. In the June of 1892, just when the wonderful peach trees were putting forth little green balls of fruit, they died. Not in a month, or a week; they died in three days. Every leaf fell from the shrivelling twigs, the young fruit fell, the dead trees stood out desolate against the landscape in early summer. And the flowers, that had been so brilliant, became very ordinary flowers, indeed, and never afterward did Garretson possess that power which had been the subject of so much comment

"Four days after this strange occurrence a telegram was handed to Garretson while he sat in his lonely room in the boarding house. It was from Professor Lassalle and read: 'Come at once. Ruth is dying and calls for you.'

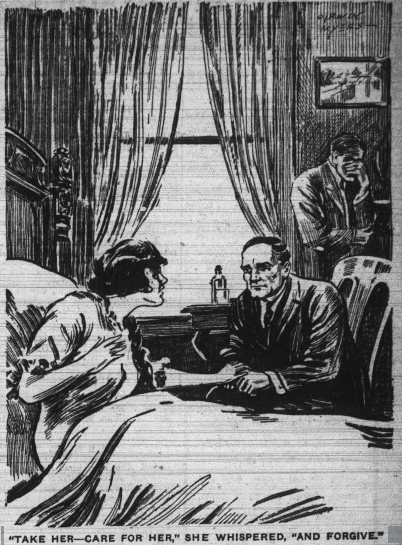

"Garretson arrived ten minutes before she died. She had given birth to a little girl three days before—about the time when the peach trees died. When she saw Andrew enter her room she turned to him with all her remaining strength.

"Take her—care for her," she whispered. "And forgive."

" 'Take her—care for her,' she whispered. 'And forgive.' That was all she could say. Afterward Lassalle told Garretson that with the birth of the child she had seemed to experience a sudden revulsion in her feelings toward Andrew. She could never have lived, not with the most skilful surgeons in the world attending her. But she seemed to think of nothing but her unkindness to her husband's old friend, and she had expressed the wish that Garretson should be her child's guardian, if he survived her husband.

"Well," said Doctor Immanuel, rising from his chair and pacing the room quickly, "that is all there is to tell. Lassalle died two years afterward and Garretson became the guardian of Miss Margaret. She has been like a daughter to him, but, as I said, Garretson is afraid that a deeper sentiment may develop on her part, as it has on his, and to avoid that he is sending her to England, at the cost of a great deal of suffering. It is odd," he added, "how men like Garretson, who are by nature affectionate and dependent for their happiness on a happy home life, should be continually crucified in their loves."

Paul Tarrant stood up.

"Now let us analyze this story of yours, Immanuel," he said. "It seems to me you are making a mountain out of a molehill. The theory you are putting forward is, of course, that Miss Margaret Lassalle is the reincarnation of her half-sister, Miss Mary, and that the mother, realizing this with the approach of death, made Garretson her guardian."

That is my theory," answered the doctor, smiling. "Well, have you a better one, Tarrant?"

"And that Miss Margaret passed a prior, or rather between-stages existence, as an orchard of peach trees. Now, my dear doctor, are you not aware that the life of the peach tree is only twelve or fifteen years? Suppose the orchard did die suddenly? Perhaps it was nipped by a late frost. Good heavens, Immanuel, as I said before, are you going to bring me back to earth as a bushel of sweet peas or a couple of hundred beds of geraniums?"

"This is my interpretation," answered the doctor, ignoring the other's outburst. "I can imagine Mary Lassalle, discarnate, her whole desire centered upon one person—Andrew Garretson. I can picture to myself the frantic efforts of this discarnate personality to clothe itself in flesh again—impossible, for the simple reason that the mechanism was not at hand, that the psychic framework for the new organism had not been built up slowly, during the centuries, out of the satisfaction, in heaven, of the soul life. In other words, she could no more come back to birth immediately than the peach tree could grow fruit before it had blossomed. Yet these ineffectual efforts did project her will into physical manifestation. A part of her personality, the part that loved, became entangled in the body of our remote ancestors, the trees—which, as you know, are biologically constructed from protoplasm, as we are, and different from animals only in the lack of a nervous system (very significant, that, if you will reflect). And so the loving part of Mary Lassalle, the part, that loved but could not suffer, grew, Dryad-like, into the trees and flowers, blindly, instinctively, but not of volition, Tarrant. It was not till ten years had passed that the soul could, by its superhuman efforts, find the bodily vehicle for itself again. And the rest you know."

"Bah!" said the millionaire, flinging the end of his cigar into the fire. "Your theories are—excuse me—sometimes ludicrous."

"Then all mythology is ludicrous," replied Immanuel. "The goddess Daphne was not changed into a Laurel, there never were tree spirits, the ancient Britons were lunatics to worship the mistletoe, and the story of Proserpine is not even founded upon truth."

"Why, who in the world supposed it was, Immanuel?" asked the millionaire.

"Do you imagine," asked the Greek, buttonholing the other and smiling up imperturbably into his face, "that religious symbols and mythologies which lasted for uncountable centuries were really founded on nothing at all?"

"On nothing at all," said Tarrant, smiling.

"You don't believe in Santa Claus, for example?"

"Believe in Santa Claus!" exclaimed Tarrant. "Well—hardly."

"And yet I saw you last Christmas wearing a white beard and a long red dressing gown and creeping into your little boy's room—"

"O, well," said Tarrant, a little disconcerted, "that was just pretense, you know."

"But you found it necessary to invent or rather sustain the Santa Claus myth in order to embody certain deeply felt spiritual needs—the love of children, the Christmas spirit—for instance."

"If you like, Immanuel."

"Then," said the doctor triumphantly, "so long as you keep your Santa Claus I'll keep my peach trees."

And so we went out, Tarrant and I, leaving the little doctor standing before his fire like a benevolent gnome, a child at heart, an incurable romanticist.

"He'll never grow up—God bless him," said Tarrant to me.

It was not late. We walked up the avenue in the moonlight, enjoying the balmy air of the spring. The trees in the square were almost in full leaf; it was not so very long since the band had ceased playing, for the park was still tenanted by a few couples who occupied isolated seats, absorbed in each other, forgetful of the world.

"Let's sit down awhile," suggested Tarrant, and so we took our seats at the back of a huge tree, where, hidden from the sight of the streets, we seemed to be in fairyland. Tarrant prodded the ground with his cane.

"It's very odd," he said, "very odd, the way that little doctor gets hold of one and grips one. Don't you find it so? That yarn of his about the peach orchard, for instance—absurd, the very height of pathos, and yet so appealing. Poor devil—l wonder if Garretson hasn't a chance with the girl. I don't think fifty-five is so very old, in the case of two people so singularly well assorted. Do you? Why, hang it, I'm fifty-five myself next fall."

We were speaking low, almost whispering, and now we became aware of a couple upon the bench adjoining ours, but so hidden by the leafy frondage of a lower branch of the tree that we had not at first observed their presence. As for them, they seemed to be entirely oblivious of anyone or anything.

"And you have really always loved me?'' whispered the girl.

Tarrant nudged me. "Don't go," he said. "We're too near—it would disconcert the poor things horribly. As I was saying—" But neither of us could avoid overhearing.

"I have always loved you," said the man, "ever since I first knew you. I have only loved once in my life before, as you know, and I love you as much as I loved her."

"Then," said the girl triumphantly, "if you have always loved me as much as Mary, why did you wait until I told you, and why did you want to pack me off to England, to that old music college, Andrew?"

Tarrant turned a scared face toward me.

'l guess we'd better go now," be said, "Softly! Softly!"

Part of the series Phileas Immanuel, Tracer of Egos

Image Credits #

Story illustrations from The Evening Republican, February 26, 1917. The artist appears to be Irwin Myers.

Pelorus Jack photo: from Thomson, G.M. Wild Life in New Zealand Part I.--Mammalia (1921) (Project Gutenberg)

Van Gogh painting: Wikimedia