Paul Tarrant, the millionaire, and I had received invitations from Dr. Phileas Immanuel to a little dinner which he intended to give in his apartments at the "Monticello." We were to meet a patient of his, and the Doctor had intimated that the case possessed unusual and interesting features. We arrived almost together and were shown up to the Doctor's quarters, where we were introduced to a Mr. Robinson and Miss Gladys Aldyne, his fiancee. Miss Aldyne was a charming girl, of the sweetest and liveliest nature, and we all got on capitally together.

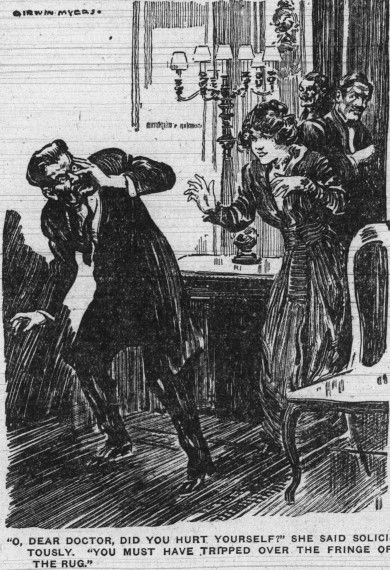

"O, dear Doctor, did you hurt yourself?" She said solicitously. "You must have tripped over the fringe of the rug."

"Mr. Robinson is one of my oldest friends," explained the Doctor. "In fact, I facilitated at his present incarnation, when his father was Consul-General at Athens, twenty-six years ago."

"I trust you will facilitate at many incarnations more," said Seth Robinson, quizzing the little Greek. "If you hadn't that reincarnation craze, Doctor, I should call you a really great man. And if you can cure my trouble," he added in a low voice, with an involuntary glance at Miss Aldyne, "I shall consider you the most wonderful man alive."

Dinner was served and proved excellent. The Doctor had some huge ripe Peloponnesus olives, I remember, and the taste of them and of his wine lingers in my mouth yet. I noticed, however, that he would not let Miss Aldyne have any wine.

"Fill my glass, please," said she to the servant; and when the man drew near the Doctor held up his finger. "No!" he said curtly.

The change in Miss Aldyne's expression was astounding. I was totally unprepared for such a glance as she shot at Immanuel, or for the explosion that followed.

"You are forgetting yourself!" she exclaimed, starting up in her chair, and pointing her finger at him with a gesture of the utmost approbrium. "How dare you say that I am not to have wine! Are you out of your senses?"

"No wine," replied the Doctor blandly, and the servant withdrew. Miss Aldyne stood glaring at him for a full half minute, the Doctor returning her gaze with an expression of polite determination. Then Miss Aldyne sat down with a bewildered air, and a moment later was chatting as naturally as ever. I was convinced that she had totally forgotten her outburst.

It must have been so, for when we rose from the table, waiving the privilege of our smoke, Miss Aldyne took the Doctor by the arm and hugged it. "Dear Dr. Immanuel, you are so good to us all," she said. "Do you know, Mr. Tarrant, he insists that I am a patient of his and suffer from neurasthenia. Seth brought me to him, and I think I allow the relationship of doctor and patient to continue because I can't bear the thought of ever losing him."

"You'll never lose me, my dear, patient or no patient," answered Immanuel, patting her hand. "Well, let's go in."

A pleasant chat followed, perhaps of an hour's duration. Then occurred another singular outburst on Miss Aldyne's part which positively horrified me.

She had been turning over the pages of a photograph album, containing snapshots taken by the Doctor in India, and had been chatting with us in the most natural way in the world. Suddenly something happened. I realized that the atmosphere had become tense. Dr. Immanuel was the first to notice the change. He crossed the room hurriedly and took the album from the girl's hands. As he did so I saw that she had been looking at a photograph showing a temple filled with images of gods.

"Let me show you something else," said Dr. Immanuel.

The girl did not answer him. She was standing up stiffly, and looking at Mr. Robinson with the utmost hatred. She did not notice Immanuel at all.

Her hate seemed too intense for words, and the poor fellow hung his head shamefacedly. Evidently it was an accustomed scene; in her hysterical moods, I imagined she became abnormal in this manner. Miss Aldyne crossed the room toward Seth Robinson, her arm aloft, as though she wielded a whip and he were her slave. Then Immanuel interposed.

"Sit down in that chair!" he commanded curtly.

Miss Aldyne turned on him; she seemed about to obey; when all in an instant she had driven her fist into the Doctor's face and knocked him down. It was a splendid manifestation of strength, and delivered with a singular deliberation, as though Miss Aldyne were accustomed to knock down all who offended her.

We all stood rooted to our places. Dr. Immanuel rose up slowly. There was a fleck of blood upon his lip, where the blow had fallen. As he got on his feet, however, Miss Aldyne sprang toward him with an expression of the utmost concern; again she was the happy, vivacious girl of two minutes before

"O, dear Doctor, did you hurt yourself?" she asked solicitously. "You must have tripped over, the fringe of the rug. I hope you are not hurt. No—yes, there is a mark on your lip; it is bleeding."

"It is nothing," answered the Doctor calmly. "Won't you all sit down, please?" he continued. "It was all my fault; I shouldn't have left those gruesome Indian photographs lying about," he whispered to Robinson, and the poor fellow nodded miserably.

Half an hour later the couple departed, she clinging to his arm and looking up into his face with manifest adoration, he obviously enthralled by her, and trying to conceal the unhappiness about which she rallied him.

When he had seen them to the door, Dr. Immanuel came back. We sat round his fireplace and clipped off the ends of our perfectos.

"Well, gentlemen," said Immanuel, leaning against the mantel, which was too high for him, and made him look like a beneficient gnome, "I told you that this case possessed interesting features."

"Yes," answered Tarrant, "you did. What is it? Demoniacal possession?"

"Pooh!" answered the Doctor lightly. "I don't believe in that."

"The New Testament is full of it."

"Yes, but the demon of those times did not correspond to what we call the evil spirit," answered the Doctor. "The demon, or daemon, as it was spelled, was simply an inner monitor, a friend who watched over one. Socrates had his demon1

(1) "You have often heard me speak of something related to the gods and to the daimones, a voice... This thing I have had ever since I was a child: it is a voice which comes to me and always forbids me to do something which I am going to do, but never commands me to do anything, ... "

--- Plato, The Apology of Socrates, 31c-d (Benjamin Jowett, translator) who always advised him when he was in doubt. Don't you remember, in that splendid speech of his before the judges who sentenced him to death, he refused to purchase his life by ceasing to preach, and told them that he believed death must be a good thing, because his demon had not dissuaded him2 from the course he was taking?

(2) "In the past, the oracular art of the superhuman thing [to daimonion] within me was in the habit of opposing me, ...if I was going to do anything not correctly. But now that these things [impending death]...have happened to me—things that anyone would consider, by general consensus, to be the worst possible things to happen to someone—the signal of the god has not opposed me..."

--- Plato, Apology, 40a-b (Jowett, translator) No, Tarrant—there may be devils that take possession of human beings, but I am very, very sceptical. What the evangelists called demons were simply the previous personalities in the subjects, trying to live again in the present incarnation."

"You mean," I said, "that Miss Aldyne's personality in her previous existence is trying to oust the present one?"

"Yes—precisely," the Doctor answered. "It's succeeding, too. When my friend Robinson brought her to me she was simply moody and neurotic. Now she is fast losing her mind. The old personality is conquering the present one. I am afraid I shall have to kill it," he continued. "But it's a hard thing to kill."

As we made no reply, he continued:

"It's a curious case, and yet many of these cases of double personality are reported from time to time. Usually, however, they represent mere fissures in the stream of the present personality. There is the famous case of Miss Beauchamp, Christine Beauchamp was the pseudonym of Clara Norton Fowler, one of the earliest diagnosed cases of dissociative identity disorder. Her case was investigated by neurologist Morton Prince, who published a book about the case in 1906. Most modern discussions characterize Ms. Beauchamp as having three distinct personalities (B-I, B-IV, and "Sally"), but Dr. Prince did make some finer distinctions. I'm sure whether they add up to nine. for instance, to be found in all medical books upon this subject, in which a single personality divided into nine parts, many of them hating and plaguing each other. One of these personalities would take possession of the subject and stuff beetles down her back, afterward awakening the dominant self, which had a horror of beetles.

"However, in this case we have to deal with two antagonistic personalities, one of which has lived its life and has no business meddling here. In the Miss Beauchamp case the problem was to unite the nine several strands into one. Here it is to kill the usurper. And I shall kill her—that woman who knocked me down—just as easily as I would kill a rat."

He looked like a fierce little fighter as he stood there, clenching his fists at the memory of the blow. And yet, I don't think Immanuel would have killed a rat. Stay, though, I remember now a certain story of a vivisection; but that has no place here.

"Did you ever read Hans Andersen's Fairy Tales?" continued the Doctor. "If so, you are acquainted with the Danish legend The general motif that Dr. Immanuel refers to is what folklorist Gordon Hall Gerould called The Grateful Dead and the Poison Maiden. While these are two separate motifs, the combination falls into what the Aarne-Thompson-Uther index labels ATU 507 ("The Monster's Bride"). Hans Christian Andersen's version is "The Traveling Companion (Reisekammeraten)". which appears and reappears all through those stories of the beautiful princess who was changed at night into a malignant devil, and this had to be killed or exorcised before the hero could marry his princess. Well, here is the case.

"Seth Robinson is a perfectly normal American gentleman of irreproachable character and unimaginative mind. Who was he, eighteen hundred odd years ago? Probably a simple Roman gentleman of the old, fast vanishing school which had made his country the ruler of the world. Or, since he was born in Athens, perhaps the last personality of Mr. Robinson was an Athenian gentleman. Whatever he was, his life was so normal and natural that his personality disintegrated in the proper manner. It can never be recalled."

"You mean that his last personality has utterly vanished?" asked Tarrant. "That is a hideous thought—it means annihilation."

"No more so than that the actor is annihilated when he strips off Othello's mask or Hamlet's doublet," answered Immanuel. "Remember, Tarrant, all these succeeding personalities are nothing but phantoms assumed by the larger self, the soul. You, for example, as Paul Tarrant, the millionaire, will, I hope, utterly disappear; but the underlying self, which will enter into its own heritage at death, will never die, though it may subsequently assume a beggar's robes or a priest's tonsure or a soldier's uniform. And it is right and proper that the personality should disintegrate. Suppose the actor would not lay aside his crown and robes when the curtain went down; would we not strip them from him with scant ceremony? Well, then, Miss Gladys Aldyne, that dear little patient of mine who is so happy with Seth, shall not be made the victim of her last personality. I am going to kill it. And I shall do so without compunction, for Claudia is nothing but a phantom which will not lay its trappings aside."

"Claudia?"

"Yes. That imperious, strong-fisted Roman harridan, who knocked me down because I would not give her wine for dinner and so enable her to assume the advantage over poor Gladys Aldyne. I mastered her then—but the unfortunate sight of that Indian temple reminded her of her own temples in sunny Greece and enabled her to take me at a disadvantage."

"So Gladys Aldyne was that—Claudia?"

"Unquestionably. And I think Seth Robinson, whom she hates so bitterly, was a lover that once rejected her. She seems to love and hate him with equal strength. Not much alike, the pair, you say? Well, Hamlet is not much like a clown, and yet we can conceive of an actor essaying both parts. Perhaps Claudia was the victim of circumstances; perhaps Gladys Aldyne has in her the seeds of an equally imperious nature. Anyway, there you have the two women and the man; and Claudia must be killed, stripped of every vestige of personality, and relegated to the phantasmal shadow-world to which she belongs. Soon, gentlemen, I shall let you know what my plans are."

We separated, soon afterward. My work kept me busy for the next couple of weeks, and I did not see Immanuel at all until one evening I received a telephone call from Paul Tarrant.

"Can you come down to Rutger's tomorrow and stay over Sunday?" he asked. "I have had a letter from our friend Immanuel; he says that he wants us to be his guests at a sanitarium there in which he seems to have a controlling interest. I think," he added, "that he'll have something to tell us about that strange case we saw at his rooms."

Fortunately my work enabled me to take the three days' vacation. I postponed my few engagements and met Tarrant at the station on the following morning. We ran down to Rutger's in about an hour and a quarter. In the station was Immanuel; outside was his dog-cart. Immanuel had a horror of motor-cars.

"I'm glad you managed to come," he said, when we were seated and he had touched up the pony. "You remember Miss Aldyne, poor girl?"

"Very well," said Tarrant "Have you killed her double yet?"

The doctor did not smile at the pleasantry. "I'm sorry to say events have taken a very bad turn," he said. "Claudia has become too strong for Gladys. She tried to kill Robinson last week."

"To murder her fiance?" exclaimed Tarrant.

"Yes, and in the most diabolical fashion—with a pair of shears. He called on her when she was cutting out patterns, and she was unusually affectionate, he said, and he was thrown entirely off his guard. He happened to turn suddenly and—well, he was wearlng an unusually broad belt, but he has a nasty flesh wound in the back. Claudia has mastered the art of appearing now without any premonitory symptoms indicative of the change, and she means to kill Seth. Fortunately she exhausted her capabilities for harm, temporarily, with this act, and Gladys, finding her lover bleeding upon the ground was thrown into a condition resembling catalepsy—really a neutral condition in which neither of the personalities could gain the advantage.

"Well, Seth is very fond of Gladys, but of course he took a serious view of the matter. He consulted me about the advisability of breaking off the engagement, and the upshot is that I persuaded Miss Gladys to come down here and rest for a month. Now we have her we are going to keep her till she is cured. Seth has gone off to the Adirondacks, very miserable, and that is the situation."

"And you intend—"

"To kill Claudia tomorrow, or as soon as she gives me the opportunity. Confound that woman!" he added, in a manner which would have been amusing under other circumstances, "what does she mean by trying to murder Seth—the best fellow alive? Why, she ought to have been in her grave for eighteen hundred years."

"Perhaps she doesn't know that she is dead," I suggested, and a moment afterward repented what seemed to me a very foolish speech. But Immanuel looked at me in surprise.

Why, my dear fellow, positively that never occurred to me," he said.

The sanitarium was a finely-located new building, containing single rooms and suites for the patients, set in the midst of several acres of grounds, and fronting on a small lake. There was a small resident staff of physicians and nurses, over whom Dr. Immanuel wielded unquestioned authority. I learned afterward that these doctors were drawn from all parts of the world, and consisted of advanced thinkers, like himself; thus any friction which might have been caused by Dr. Immanuel's unusual theories was obviated. We were accorded rooms in the physicians' part of the house, and met Miss Aldyne at dinner an hour or two later. She knew us immediately, and was very merry over her situation.

"You didn't think, when last we met—or first, rather—that our next meeting would be in a lunatic asylum, did you?" she said to me.

"O, come. Miss Gladys—not a lunatic asylum!'' protested ImmanueL

"Well, Doctor, if some of these people aren't off their heads I don't know what is the matter with them," she answered, and I saw a momentary expression of fear come into her eyes.

"My dear Miss Gladys," said Immanuel gently, leaning toward her, "you trust me don't you?"

"Yes," she answered seriously, "but why doesn't Seth come to see me?"

"You don't trust me, then?" asked Dr. Immanuel.

"Of course I do,'' she answered. "But if you weren't here—well, I should be terribly frightened. And you'll tell me about Seth soon?"

"My dear, in a couple of days I think you shall see Seth for yourself and have your fears allayed. Now—will you be cheerful till Monday?"

She nodded. Suddenly I felt—I saw no change but felt —that sense of oppression again, as though something malignant were near, something dangerous and terrible. I think Tarrant felt it, too. Miss Gladys had taken up her knife to cut her portion of meat; it slipped out of her hand, and the fragment, with a little spray of gravy, went into the face of the Doctor, who wak still leaning toward her. He drew back hastily, wiping his eyes, and Miss Aldyne was instantly all apologies. But I knew and he knew that it had been done on purpose—and besides, this was not Miss Aldyne.

No, and she did not come back all during that evening. We sat with her in her private apartment, watching her and each other like cats. She chatted and gossiped—and all the while her eyes were filled with fires of slumbering hate. And presently I began to notice that our conversation was of a peculiarly restricted kind. It never dealt with current events. For instance, when Tarrant made some passing allusion to the war in China ...war in China: Probably the 1911 Xinhai Revolution, which ended the Qing dynasty and established the Republic of China. she looked at him without comprehension, and yet as though she were on her guard and dimly aware that something was wrong. And when addressed as Miss Aldyne she answered as though she had assumed that name —that is the best way in which I can explain the strange manner of her speech.

"Well, Madam," said Dr. Immanuel presently, "you are so much better that I think we can let you go home tomorrow. You seem to have realized now that your beliefs are only illusions, have you not?"

"My beliefs?" she answered, as though with an effort of thought. "Yes—I think so."

"For example, that absurd delusion of yours that you have some outlandish name like Gladys, and that you are engaged to your worst enemy— ''

"Crassides!" she exclaimed, as though the name had suddenly come into her mind after she had long forgotten it

"The man who insulted you and spurned your love," went on Immanuel remorselessly.

She clenched her fists and closed her eyes and lay back in her chair, apparently overcome with the most intense accession of hatred,

"But he is dead!" she cried, starting up suddenly, like a fury. "I poisoned him."

"At the banquet?"

"What else should I have done?" she cried, "Yes. I bade him to the banquet and lavished caresses and loving words on him. Then when the wine was to be drunk I had set before him a goblet into which I had poured Parisian poisons, so swift that one dies instantly and without knowledge of it. It had been my purpose to give him that German drug which brings a sure and lingering death. I had wanted to gloat over him, dying—but my heart misgave me. I could not torture the body that I had loved. So I chose Parisian poison, subtle and very swift. And then I pledged him, and we drank; I from my goblet of pure wine and be from his poisoned cup. And so he died."

"Ah! You are sure he died?" asked Immanuel keenly.

A convulsion seemed to seize her. Her lips parted, she glared at him, seemed about to answer—and then Gladys Aldyne was looking out of her eyes at us. She looked, round blankly.

"Why, my dear Doctor, how in the world did I get up here?" she asked. "I thought we were at the dinner table."

"Ah! You forget," answered the Doctor lightly. "But your memory is growing stronger, my dear. We'll have you out of here and back with Seth next week. And now I am going to send you to bed. You want all the rest you can get. Good night"

"Good night, Doctor," she answered, taking his hand in hers affectionately. She bade us good night also, with less spontaneity but much good will, and so we left her.

"Well, gentlemen," said the Doctor, as we lingered at his door, "tomorrow I hope to exorcise Mademoiselle Claudia for ever. I have learned quite a good deal about her. She was the daughter of a Greek senator, an only child, and mistress of a household of slaves, whom she abused in quite the conventional fashion. Her memory is pretty clear, but when she spoke of Parisian and German drugs there was a little confusion—she meant Egyptian and Scythian, probably. What part young Crassides played in her affairs you learned this evening. I have a certain theory which I think will enable me to put her back in the limbo to which she belongs—but I have had a devil of a time waking her up sufficiently to learn her history. You won't forget that exquisite confession she made about the poisoned cup? All right: one word more. Tomorrow night we four dine alone in a private dining room which has something of the character of a property room. There I reconstruct my scenes for just such occasions as this present one. And, gentlemen, you will not see Miss Gladys tomorrow before dinner—nor Mademoiselle Claudia, either."

Nor did we see the Doctor. We spent the day strolling round the fine grounds of the institution, and in looking over the interior. The arrangements were perfect, and the patients all sufferers from those forms of mental maladies in which Dr. Immanuel was a specialist. He did not, I was told, take any incurable cases.

At six o'clock there came a tap at my door. I opened it—to find the Doctor standing outside, wearing a long cloak which completely concealed his figure. When he came in he threw it off and disclosed himself in an ancient Greek costume. And it suited him far better than modern clothes, in which he always had the look of a masquerader.

"I have brought you a tunic and toga," he said, depositing a bundle upon the bed. "You don't mind?"

"Not at all," I answered. "And Tarrant—"

"I expect he has put his on already," answered our host, laughing. "By the way, you can preserve the illusion? I have had the room fitted with banqueting couches and all the apparatus. All right; take the private stairway down and it is the third room—the locked one."

Half an hour later we were awaiting Immanuel and his patient in a room which might have been the interior of a Greek house, so well was the illusion maintained. I looked at Tarrant, reclining on his divan in flowing robes of white, and he looked at me.

"'One man in his time plays many parts,'"

"All the world's a stage, / And all the men and women merely players; / They have their exits and their entrances; / And one man in his time plays many parts."

-- Shakespeare, As You Like It, Act II, Scene VII he quoted. "But, seriously, I shouldn't like my business friends to see me now."

Steps, as of clogs, were heard outside, and Immanuel entered, in company with Miss Gladys, who was wearing a gown with lace at the sleeves, and a little pearl necklace, the gift of Robinson. She looked at us in astonishment; and when Immanuel threw off bis cloak and stood revealed in toga and with sandaled feet her amazement was about equal to our sense of playing the fool.

"Why, my dear Doctor— '' she began.

"Never mind, never mind," answered Immanuel briskly. "This is part of a play."

"But, Doctor, I don't understand. I never heard of such a sanitarium as you seem to run. Is this part of the cure?"

The little doctor was staring at her in disgust. Evidently the venomous Claudia was wary and, warned by some instinct of approaching danger, absolutely refused to make her appearance. But Miss Gladys was always gentle.

"Well, Doctor," she said, sitting down on a carved chair which looked like the section of a boat, "what is my part? What am I to do?"

"Why, we will just have a little visit," answered Immanuel. He was parrying to gain time. But even he looked overwhelmed with confusion.

"What setting is this?" Miss Gladys asked. "Ancient Roman?"

"Greek, my dear," said the Doctor. "Purely Greek. No doubt you yourself once knew this setting very well."

Miss Gladys laughed. "I see you will never get rid of that craze of yours," she said. "Do you know, Doctor, sometimes I think you ought to be a patient here, instead of chief physician."

We twirled our thumbs. I tried to hide my bare feet under my flowing robe. The minutes passed in desultory conversation. The Doctor rose and taking an amphora of wine from an ancient stand, filled two chalices of purple glass. "Will you drink with me, Claudia?" he asked.

"Claudia!" said Miss Gladys, rising up and looking at him with an expression of distinct terror.

Suddenly the tramp of heavy footsteps rang out on the flags. The door opened. Seth Robinson burst in.

"I couldn't stay away any longer," he burst out. "I'm going to take Gladys away. I must, Doctor; I want her and I've behaved like a cur when she was in trouble, poor girl. I—"

Suddenly he perceived us in our Greek attire, the couches, the amphora with the two cups of wine. He looked round in amazement, which rapidly became anger. Dr. Immanuel slipped behind him and I heard the key click in the door.

"What is all this?" inquired Seth Robinson angrily.

"Look behind you!" I yelled.

He leaped aside, and fortunately in the right direction. There at his side stood Claudia, livid with fury, her fists clenched, her eyes blazing. A surgeon's scalpel was quivering in the wall opposite, in a direct line with Robinson's shoulder. She must have hidden it before she entered.

Immanuel sprang to the table and seized the cups of wine. He handed one to Robinson. "Drink when I give the signal," he hissed in his ear. "Don't speak, don't question; drink, for all you want in the world depends on it."

Robinson, trembling, took the cup, and the wine lapped over its edge as he tried to steady it. To Claudia the Doctor gave the other.

"Will you not drink with Crassides?" he asked, assuming the attitude of a toastmaster. He raised his hand. "Face her, Seth," he said in a lower voice. The man and woman were almost side by side. Claudia, holding her cup extended in one hand, with never a tremor of the glass, placed the free arm round Robinson's neck. She looked lovingly and inquiringly at him. They raised their glasses together and drained them. Then Claudia dashed hers down on the mosaic floor.

"You fool!" she hissed, "Now die, you who scorned me!"

"O, come, Gladys, I never scorned you," said Seth Robinson in a sorrowful voice. "Is that why you flung the knife at me?"

The situation was on the verge of pathos. But the denouement came so swiftly that its instant purpose escaped me. I saw Immanuel spring to Claudia's side and whisper something and point to Robinson, saw a look of intense terror come into her eyes; and then she went down, a crumpling heap upon the floor.

"You've killed her," shouted Robertson, leaping at Immanuel's throat.

"No, my dear boy. I have saved her," he answered, tenderly raising the prostrate form, "Now carry her out. Gentlemen, disappear before she recovers and sees you in that costume." He locked the door and I saw him helping Robinson to place Miss Aldyne on a couch in the halL Then as we ascended the private stairway Immanuel came pattering after us.

"Victory!" he cried, seizing our hands. "Already she is reviving, and there isn't any mistake about who she is now, or who she is going to be. Claudia is dead!"

"She may come back," hazarded Tarrant.

"No, my dear boy," Immanuel answered. "She's dead now for ever. You see," he added, "one of her slaves, who hated her, had changed the cups, so that Crassides escaped alive, and Claudia died so quickly that she never knew she was dead. I've just convinced her."

Part of the series Phileas Immanuel, Tracer of Egos

Story illustration by G. Irwin Myers, for The Evening Republican, April 18 1917. Source: Hoosier State Chronicles.