I remember this conversation almost verbatim, because it was so appropriate to the incident which followed it. First, I will recount the conversation, which the visitor interrupted.

Although he was not admitted to practice medicine in America—for money, at least —Dr. Phileas Immanuel, the famous neurologist who had come from Greece to attend some conference or other, was frequently called upon to give his services gratis to those who knew of his special skill in cases of obscure nervous diseases. It had come to be understood that he could be consulted most evenings during the remainder of his stay, and on this evening he was expecting a visit from a gentleman who had sent him a rather urgent letter, making an appointment. Consequently Paul Tarrant and I ought not to have lingered. But the Doctor's conversation was always fascinating, and neither of us could tear himself away. Dr. Immanuel, posted before the fire in his consulting room, his hands beneath his coat tails, was haranguing us, and we were listening.

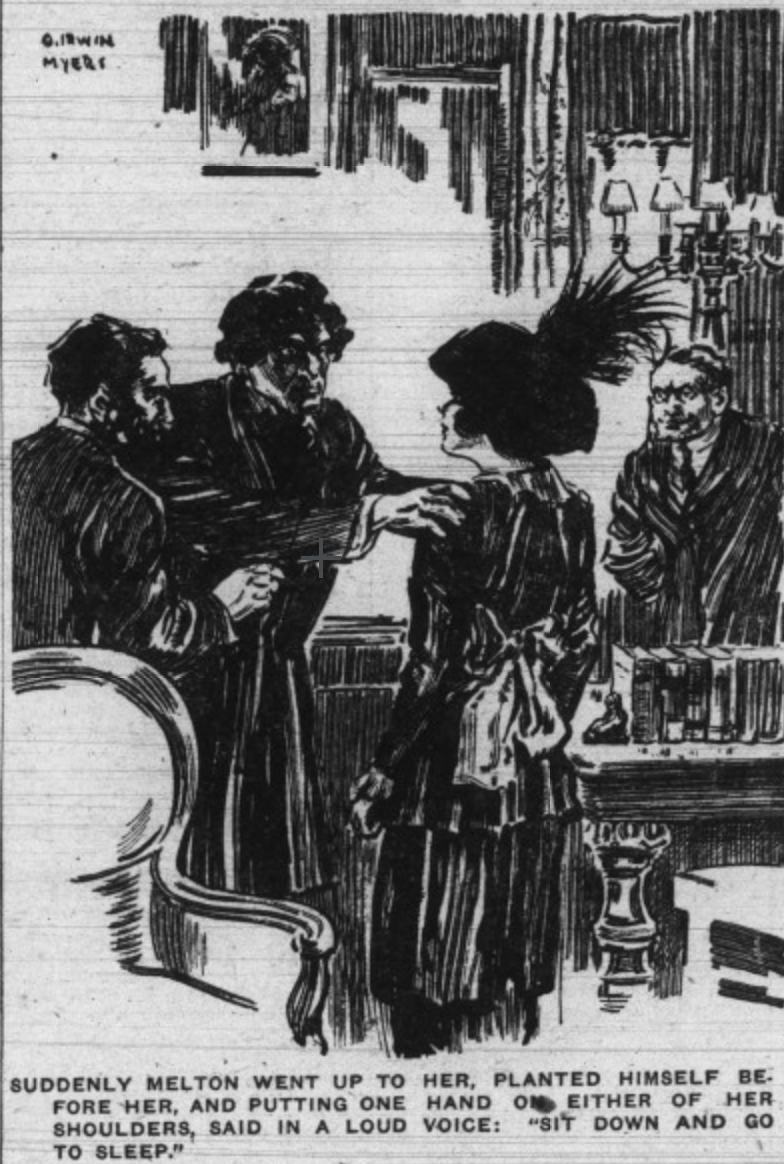

Suddenly, Melton went up to her, planted himself before her, and putting one hand on either of her shoulders, said in a loud voice: "Sit down and go to sleep."

"You mean," interrupted Tarrant, "that if only the theory of reincarnation were admitted into the pharmacopeia, physicians would have a complete method of treating these cases of aphasia, amnesia, and secondary personality that you have been illustrating?"

"Not secondary personality, Tarrant," returned the Doctor irritably. "There is no such thing. Say rather 'incomplete personality' or 'lumber room personality,' but not 'secondary personality.'

"Put it this way," he resumed. "It is a favorite illustration of mine, but it is the best I know. Suppose that Mr. Lewis Waller, William Waller Lewis (1860-1915), stage name Lewis Waller, was an English actor and theater manager, known for his Shakespearean and romantic lead roles. (Wikipedia) whose impersonation of Henry V has made him a universal favorite, should be cast in the role of Hamlet. Well, now, perhaps he has eaten too much or too little, perhaps be has a bad cold or some mental trouble which temporarily upsets the co-ordinative faculties of his mind. Well, instead of beginning his famous soliloquy he begins the speech before the battle of Agincourt, in a moment of absentmindedness. Is that 'secondary personality,' Tarrant? Not at all. He has simply pulled Henry V out of the lumber room of his memory in place of Hamlet.

"So it is in these cases that I have mentioned. These people who forget who they are, or imagine they are others—they are really one and the same individuality, but instead of playing the parts assigned to them in this incarnation, they pull out some old part which they played fifteen hundred or three thousand years ago. We live"—I remember these words of the Doctor's vividly in the light of what followed them —"we live, my dear Tarrant, a very much deeper and bigger life than you or I have any idea of. It's the deeper life that counts, not this surface life with its conglomeration of chances and accidents. We live at once the whole life and the part life. The trouble with us is that we center our personalities in the superficial top layer."

There followed an agitated ring at the bell, and a minute later the attendant was showing the patient in. Dr. Immanuel, like most big men, did not keep his patients waiting in order to magnify his own importance.

The man who entered was a well-dressed, handsome, aristocratic looking young fellow of about eight and twenty. I started to make my adieux, but Tarrant, instead of accompanying me, went up to the visitor and greeted him cordially.

"Why, Morton, I haven't seen you for ages," he said. "Nothing serious, I hope, with you or Miss Digby, that brings you to our friend Immanuel?"

"You know each other?" asked the Doctor in surprise.

Tarrant smiled. "Jim Morton and I have lived on the same block for years," he answered. "I own most of it now, but there will always be space for Jim's house."

Then I was introduced and we started to go. But Morton detained us.

"You'd better stay, Tarrant—and your friend, too," he said. "The news will be all over town tomorrow or the next day, and upon my soul I'd rather it leaked out piecemeal than have the revelation strike everybody at once. Please sit down—both of you."

We obeyed, and a couple of minutes later Morton was pouring out his troubles to Dr. Immanuel.

"I don't think you know my fiancee, Miss Katherine Digby," he said. "Of course you don't, seeing that you have never met me before. I suppose I forgot for the moment, meeting Tarrant here, that you aren't one of our set. You see," he said apologetically, "everyone in the neighborhood has known us for a good many years."

Immanuel checked him gently. "I am to understand from your letter that Miss Digby suffers from some nervous trouble?" he asked.

"I don't know," exclaimed the other, starting out of his chair and sitting down again. "I hope so. Indeed I do. But if it is true, what she told me—that she was married seven years ago—"

Tarrant gasped and checked himself upon the verge of an exclamation. I saw his lips form the word "impossible," and he began shaking his head.

"If it is true," cried Morton, "I don't know whether to be more sorry for myself or her."

"Now, my dear fellow, let us get at the story systematically," said the Doctor. "When did she tell you this?"

"Yesterday afternoon, when I was calling on her. We have been engaged three months and expected to be married in about six weeks' time. Miss Digby has never shown any signs of abnormality except that she is given to what is called 'day-dreaming.' Frequently she falls into a brown study which lasts a couple of minutes, and during that period she is entirely oblivious to what is taking place around her. But that is of no significance."

"Pardon me; it is of the greatest significance," replied the Doctor. "It is a true trance condition, of a limited kind. It is a process of auto-hypnosis—self-hypnotism, that is to say—which may reveal a great deal to the specialist. But proceed!"

"I had grown accustomed to these states, which do not occur with great frequency," continued Morton, "but yesterday I was a little piqued that one should occur at a time when she had given me reason to believe that—well, that she thought a good deal of me. And so I shook her gently, to bring her out of it."

"My dear Mr. Morton! You might have done serious harm. And then she made that astonishing statement to you?"

"She turned around and, without the slightest expression of shame or guilt, informed me that she was married, seven years ago, in the Harmony Hall, a low sort of dance hall across the Avenue, to a man called Ira Hopkins."

"What, Hopkins, the corner grocer?" shouted Tarrant, leaping out of his seat

"Yes," answered Morton, overcome with emotion. "Of course, it was fantastic. An instant later she came out of her reflections and gravely told me that she loved me with her whole heart. I made some excuse, hurried out of the room, went home, and wrote that letter to you."

"And you have not seen her since?"

"No. I have written saying that I was called out of town on urgent business. What can I do, Doctor? I feel that I shall go mad."

"Have you spoken to this man Hopkins?" asked Tarrant.

"Of course not, you idiot!" Morton angrily. "Why, confound you, he has a wife and three children."

"Have you examined the marriage records?" asked Immanuel.

James Morton scratched his head in perplexity. "I never thought of that," he muttered shamefacedly.

"It is common, among hysterical persons, for them to accuse themselves of all kinds of things," continued the Doctor kindly. "Now don't you rush off to the marriage bureau. Go out of town at once, as you have said, and stay away for a week. At the end of that time come back and you shall know the truth."

"A week!" cried Morton. "I can't wait a day. Why, you can find out in an hour."

"Hardly that," answered Immanuel quietly. "The old records are at Albany, you know."

"Three days, then."

"I said a week," replied the doctor inflexibly. "If you cannot accept my proposal—"

"You promise to have the whole problem settled when I come back, then?"

"One week from tonight," replied the Doctor. And after a rather painful scene Tarrant and I got the poor fellow out of the room and took him to his home.

I heard nothing more for I think five days, except that Tarrant called me on the telephone the following morning and told me that he had stayed the night at Morton's house and had seen him off to the country early the next morning. On the evening of the fifth day, however, I received a telephone message from Immanuel, saying that Tarrant had been dining with him and asking if I could join them that evening. I found them talking earnestly together in the consulting room. But when I spoke of the case Immanuel seemed slightly embarrassed.

"The fact is," he admitted, "all depends upon the result of this evening's work; that is why I asked you to come in as a witness. I have had the marriage records examined and there is certainly none of such a preposterous union as is supposed to have occurred. But, as you may know, some of the records were destroyed in the Capitol fire, and it is possible that this was among them. I have made the acquaintance of Hopkins. He is a nervous little man with a placid wife and three lively children, and betrayed no embarrassment at the casual mention of Miss Digby's name. Then, too, I took the liberty of visiting Miss Digby, representing that I was her fiance's physician, and I think I have discovered the secret. The story of the marriage was totally false—but it is, in a sense, true. Literally, it is false. Morally, it is true. Legally, she is not Hopkins' wife. Actually, she is. Her personality, as it appears in its present incarnation, repudiates all knowledge of the little grocer. But the wider personality, the real Miss Digby, is married to him."

"You mean that she was his wife in her last incarnation?" I asked, startled.

"Heaven forbid!" answered the Doctor fervently, and Tarrant replied "Amen!"

"No, this is the solution," explained Immanuel. "Seven years ago, when she was a girl of sixteen. Miss Digby went, with a girl friend of hers, to Harmony Hall, to hear an itinerant hypnotist—a veritable charlatan, one of those men who travel round the country, exhibiting the very ordinary phenomena of hypnotism to a gaping, ignorant public. The man invited Miss Digby to become one of his subjects, and, like a silly child, she was persuaded. He easily placed her under hypnosis, and then, having made her perform foolish antics, for the amusement of the spectators, and having possession of the name of Ira Hopkins—to obtain local data is part of these people's business—he assured her that she was his wife. That is all. Hopkins, if he was ever told, speedily forgot the circumstance, as did Miss Katherine. But you know what Scripture says about marriage. Miss Katherine, in her deeper personality, is the wife of Hopkins. Those fits of abstraction, common to many persons of temperament, represent a momentary lifting of the veil, an usurping of the wider personality into the shallower one which we know. And it was in one of those that Morton surprised her into betraying the secret. Once her normal self again, Miss Katherine knew nothing of the confession. But in her heart, her soul, though she has no feeling whatever toward the little man, she is Mrs. Ira Hopkins."

"How horrible!" I exclaimed. "What are you going to do this evening, then?"

"By a streak of rare good fortune I have discovered the man Melton, who hypnotised the young lady," answered Immanuel. "I explained the circumstances, and by dint of a mixture of threats and a promise of a couple of hundred dollars, he has been induced to meet her here this evening, hypnotize her again, and solemnly declare her to be divorced."

"It sounds fantastic," said Tarrant, "but—good Lord, Morton is one of my oldest friends—and Miss Katherine, too."

A double peal at the door bell was followed by the appearance, almost simultaneously, of the two visitors. The servant, who had been instructed to admit anyone that called, ushered them both into the room together. It was an embarrassing moment. I could see that Melton knew who the girl was at once, but Miss Katherine had not the slightest recollection of the fellow, who, with his sharp, roving black eyes and long, greasy ringlets, looked like the typical quack he was.

We were all standing there together and the situation grew more ridiculous each moment, for Miss Digby, wholly ignorant of the purpose of her visit and finding three men present besides the Doctor, was looking uneasy and coloring under the quack's scrutiny. She was a handsome, lively girl, without the slightest appearance of neurasthenia, and I expected her to turn round and go-home.

Suddenly Melton went up to her, planted himself before her, and, putting one hand on either of her shoulders, said in a loud voice:

"Sit down and go to sleep!"

A box on the ear ought to have rewarded this speech. Tarrant started forward indignantly; but before he could reach the spot, to my unutterable astonishment I saw Miss Digby sink into an arm-chair and close her eyes. Melton turned to the Doctor with a grin.

"They never forget," he said impudently. "Once you hypnotise them it's as easy as pie next time. I guess that helped you out some, eh, Doc?"

''Suppose, now that you have assumed charge of this case, that you do what you are paid to do," said the little Greek, curtly.

"I haven't been paid yet," answered Melton, grinning. "Now, Miss, sleep easy. Nobody's going to hurt you. You sit still and keep them eyes closed."

Immanuel counted out two hundred dollars and Melton counted the money again, then pocketed it "You can't make it two hundred and fifty?" he asked regretfully.

"Two hundred," replied Immanuel. "I stand by my bargains, sir."

"Well," answered Melton, "that's right. But remember, I only engaged to tell her she was divorced. I don't guarantee that it'll work."

"Why not?" asked the other, and I could see that he was worried by a sudden thought that occurred to him.

"I'll tell you afterwards," answered the quack. "Are you ready for me to begin?"

Immanuel nodded, and Melton stepped up to the girl and sat down on another chair which he drew up in front of her. He took her hand in his.

"Who is your husband?" he demanded, leering at us as he spoke.

"Ira Hopkins," replied Miss Digby mechanically.

"What is his business?"

"He has a corner grocery."

"Do you love him?" asked Melton, putting his tongue into his cheek.

"O, yes, I love him, of course," she answered.

"And how long have you been married?"

"Seven years, two months, and nine days," she said, without any apparent effort of calculation.

"Well, you ain't married any longer. You are divorced now. Do you understand?"

"Yes," she responded in the same listless manner.

"Then what is your name now?"

"Katherine Hopkins."

"Are you married?"

"Yes, to Ira Hopkins."

We looked on in amazement Tarrant I think, was contemplating attacking the impudent fellow, and he, sensing it, looked up at him in some sort of fear. "I'm doing the best I can," he said. "I can't make her believe me, can I?"

"Try again," said Immanuel grimly, and the fellow turned to the girl once more.

"What is your name?" he asked again.

"Katherine Hopkins."

"Your husband is Ira Hopkins, owner of a corner grocery, is he not?"

"Yes."

"How long have you been married?" he continued, and the same answer was returned as previously.

"Well, listen to me," shouted Melton in the girl's ear. "You ain't married any longer. Ira Hopkins has got a divorce and married again. Do you understand that?"

"Yes, I understand," said Miss Katherine.

"And what is your name how?"

"Katherine Hopkins."

Melton looked round hopelessly. Terrant looked as though he were going to spring at him. But Immanuel went up to the man and said simply: "You have done what you contracted to do."

There was a long silence. Then the Doctor turned to us. "You see, gentlemen," he said, "marrying is easier than divorcing. In fact, it is almost impossible— "

"Quite impossible," interposed Melton brusquely. "Divorce don't go in the place she's in now. That's Gospel, ain't it? I warned you, and I know, for I've been on my job for the past ten years and more, and if you'd seen as much of human nature as I have, instead of follering your book theories, you'd never have been fool enough to hand over that two hundred."

"Well, gentlemen," said the Greek, "that is all. I was afraid of it. The mischief is done and there seems no remedy"

"Unless," said Tarrant, "Morton is taken into your confidence and told just what the circumstances are. Surely, Doctor, no normal man would mind marrying a woman who believed she was another man's wife when she was hypnotized."

"That," answered Immanuel slowly, "is none of my business. If Morton chooses to marry Miss Digby under these circumstances, he must do so. But in my opinion the marriage would be no marriage at all—nothing but a legal agreement to live together."

"Good Lord, Immanuel, what ought to be done, then?"

"There seems to be no remedy," the Doctor answered. "If Hopkins were not married the only thing to do —if one wanted to be ethically correct —would be for her to go through the form of marriage with him and then separate from him. Now don't get excited, my dear Paul. I am giving you my opinion, and as a physician I cannot tamper with the truth. Personally, as a man, I think I should advise the couple to marry. Only—"

"Yes?" cried Tarrant eagerly.

"There is this to be said," continued Immanuel. "Marriage is much more than a mere legal agreement. You, as a member of your particular faith, do not consider it as a sacrament. I, as a Greek Catholic, do. But whatever our creeds may teach, the fact remains that marriage is something extending deep down under the surface layer of consciousness. It is something that intimately binds the larger, deeper, hidden self of the contracting parties. It is not only that this young lady is married to Ira Hopkins, Hopkins is also married to her. And though to the physical personality of Hopkins Miss Katherine is merely one of his customers, the deeper Hopkins knows."

"But how can she be morally married by the mere saying so of this—this gentleman?" protested Tarrant.

"Because," answered the Doctor, "the soul receives its impressions from the external personality, as the plant root through its leaves. It knows nothing of falsehood. Every suggestion made to it is accepted as true and must be transmitted into truth. You see now the consequences of tampering with truth, and the profound spiritual significance of our earthly actions."

"Good evening, gentlemen," said Melton, briskly. He had heard this dialogue, with manifest uneasiness, and now, picking up his hat he moved toward the door. Then Paul Tarrant started forward.

"Will you wait twenty minutes by that clock and then try again, for a hundred dollars?" he asked.

"I will," replied the quack. "But I warn you it won't go. You can't go against the Gospels, and there ain't no divorce recognized there—leastways, not for the mere saying it's so."

"Where are you going, Paul?" inquired Immanuel, as Tarrant started for the door.

"I'll tell you when I come back," he answered. He paused, his hand on the door knob. "This fellow Hopkins lives over his store, doesn't he?" he asked.

"Yes. Apartment 8 in the block of which the store forms a part. But why are you going? You won't be rash. Paul? Remember, he knows nothing."

"Keep cool, Immanuel. I'm not going to harm him," replied Tarrant, and with that he was gone, and we three sat there together in silence, looking now at each other and now at the hypnotized girl.

"It ain't no good," vouchsafed the quack, "but I'm willing to earn a hundred. Who wouldn't? By Jiminy, if I'd known what was going to happen that night seven years ago in Harmony Hall! But I was newer at the game then, gentlemen, and I hadn't had the experience."

"You fellows ought to be prohibited by law," said the Doctor sternly. "You play with forces whose very meaning you are ignorant of."

"Hold on there, friend," said Melton. "I go to the facts, you go to the books. What's the odds? They write the books from the facts, don't they? Now I say, if a poor feller's got a bad toothache and I can tell him he's well, and his pain stops, I consider I'm a public benefactor."

"Exactly," answered Immanuel. "And what do you do? You destroy his consciousness of pain, which would have warned him of an ulcerated tooth, and instead of going to a doctor he lets the ulcer eat down into the bone. That's your way; you cure the effects and ignore the causes. I wonder what Tarrant's doing?'' he continued, looking at me uneasily.

It was now fifteen minutes since he had gone. Only five remained, but I knew that Melton would not stir because he had not received his money. Just as I was wondering whether I ought not to go after Tarrant the door bell rang, and a minute later he came hurrying in. His face was radiant

"May I speak to Mr. Melton privately?" he asked. "I don't want to keep anything from you, gentlemen, but this is—well, it's the limit. And you'll see whether it's going to work or not when he speaks to the girl."

We excused him willingly, and be drew Melton into a corner. I saw him count out a hundred dollars and saw the quack count them again and pocket them, as before. Then Tarrant began whispering, and Melton started back and stared at him, and suddenly broke into a broad grin. All the while Miss Katherine sat perfectly immobile upon the chair.

Melton came back. "Well, gentlemen," he said, "what Mr. Terrant tells me puts another light on the subject altogether. It he hadn't thought of it and found out—good Lord! I'm sailing for Australia next month and you might never have found me again. And remember, Doctor, although you say you are the hypnotist at the hospital in Athena, neither you nor nobody could ever get that out of her mind —nobody but me, once I put it in. There's where I've got the whip hand over you, Doctor Immanuel. Think of all the wisest hypnotisers in the world trying and trying to rub out that stain, and only the one that put it there can take it out again. Am I right or wrong?"

"Unfortunately you are right, sir," Immanuel answered.

"And I ain't holding you up for another penny. Now, Doctor, confess that we professionals ain't all as bad as you paint us."

He seemed really concerned about the reputation of his trade, this quack. I have known others just as sensitive.

By this time we were all in a fever of expectancy. Melton kept us waiting no longer. He drew up his chair again and, sitting down before the girl, took her hand in his.

"What is your name?" he asked.

"Katherine Hopkins," she replied quietly,

"When were you married?"

"Seven years, two months, and ten days ago," she answered, and Melton looked round at us.

"You see, gentlemen, another day has just come to an end," he said. "It was about this time I hypnotized her in Harmony Hall." He turned to the girl again. *

"Your marriage wasn't any marriage at all," he said. "The man Hopkins, who you think is your husband, had already been married nearly two years at the time I married you to him. So it wasn't any marriage. Do you understand?"

"Yes."

"What is your name?"

"Katherine Digby."

"You will wake up in three minutes."

"Good evening, gentlemen," said Melton, and he went out.

Part of the series Phileas Immanuel, Tracer of Egos

Story illustration by G. Irwin Myers, for The Evening Republican, April 14 1917. Source: Hoosier State Chronicles.