"The doctrine of reincarnation" said Dr. Phileas Immanuel to Tarrant and myself, as we sat around the fire in his cozy consulting room, "has always been held by advanced thinkers in every civilized community. Though I am a Greek, I may say, I believe without contradiction, that the ancient Greeks were the most shining example of civilization that the world has ever seen. It was taught to them by Plato and Pythagoras, the latter having evidently brought it from India and the former having studied it in Egypt. The Mysteries of Orpheus made the belief more common among the religiously inclined. Plotinus telle us that all the world held to it about the time of our Lord. And Christianity itself is based on it."

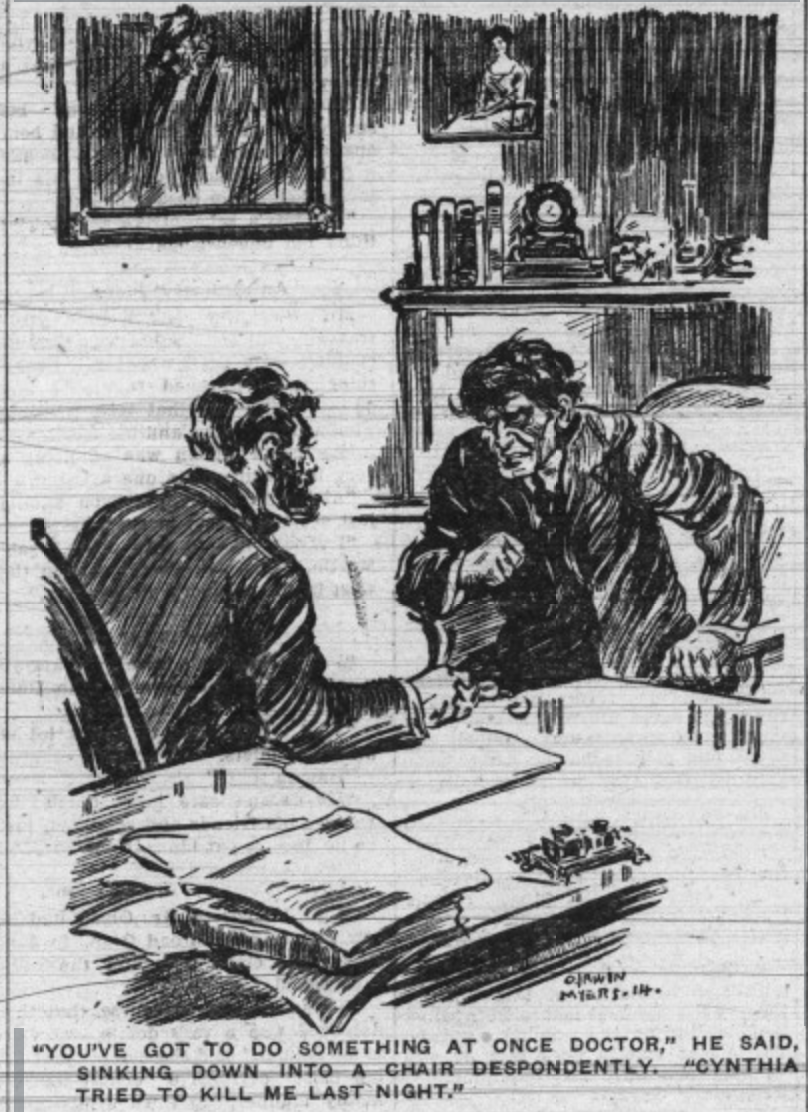

"You've got to do something at once, Doctor," he said, sinking down into a chair despondently. "Cynthia tried to kill me last night."

"But surely, doctor, the gospels do not teach reincarnation," interposed Tarrant.

"I maintain the contrary," said Immanuel. "Though our Lord frequently said that he spoke in parables, that certain things must be concealed, it is impossible to read the Gospels without coming to that conclusion. Is it not clearly stated in the seventeenth chapter of St. Matthew that John the Baptist was the reincarnated Elijah?

"Yet," he continued, "this doctrine is too immensely dangerous ever to be allowed to come into universal acceptance. Even in India the masses have but a dim understanding of it. For consider the lives of most of us, the wrongs that are done, the friendships that are broken never to be cemented, the tragic failures, the sense of world-weariness that comes upon most of us in middle life; well, if memory persisted, or if we knew assuredly that at some distant epoch we should take up our lives again, what incentive would we have to make our exits gratefully and to repair, as best we can, our faults?

"Yet there are many recorded instances where memory does persist, and I shall relate one of these to you. Here is a case where a love was so intense and the resolution for reunion so strong that it was brought to success, and because that resolution was unwise the result was not wholly satisfactory. Does either of you know Field, the author?"

"The man who wrote The Transgressors?" asked Tarrant. "I met him once, I believe, years ago. A cheerful sort of fellow with a fine sense of humor?"

"Yes," answered Immanuel. "A well poised man in every sense. But The Transgressors, which is his last book published, is not the last he wrote. His latest novel was held back from publication by the advice of Morton and James. They said it was too fanciful, that it would impair the sale of his more serious works. The plot is laid in Atlantis, that ancient continent which, as Plato tells us, sank into the sea thousands of years before the dawn of recorded history. And the astonishing thing about it is that it is not a fanciful work at all—it is a record of experience."

"How can one tell that?" asked Tarrant

"Because," answered the doctor, "Field wrote that book by automatism. You know what I mean? I believe it is not an uncommon process. Stevenson is said to have written his finest short story in the same way. Field told me that he would awake out of a deep sleep and sit down at the table, not knowing what he was going to write. As soon as his pen touched the paper, however, it would begin to scribble at a furious rate, while Field, looking on merely as a spectator, saw the story shaping itself without any knowledge on his part of how it would turn out.

"There is nothing mysterious about that process. It simply means that tbe submerged part of the personality, that part which lies just beneath the level of consciousness, assumes control of the nervous and muscular apparatus. If you have ever performed any very tedious task, such as addressing 500 envelopes from a list of names, you will know what I mean.

"But such feats have a much deeper meaning than most of us suppose. In many cases it is actually the past incarnation of the writer, or an earlier one, which he depicts. All instinct, they say, is memory, and many of our dreams are memory too. Some day we shall remember everything and fit the puzzles together; but that will be ages hence and in a different world.

"Field fell in love with his heroine. Her name was Lota; she was a daughter of a priest of the river god, destined to be a temple virgin. The hero of this weird story loved her, their love was discovered, and both were put to death, executed upon the sacrificial altar. So much for the theme. But the wealth of imagery, the realism of the story overwhelmed me when I read it. I knew at once that memory alone could have given such a store of treasure to the world. And afterward I discovered that much of the description tallied with a strange account given by the Popol Vuh, the sacred book of the Guatemalans.

She and her hero swear to meet again.

"In the last scene before the sacrificial stone she and the hero swear to meet again and fulfill their love though a thousand lives intervene between that and the one so soon to be ended. Then their breasts are rent by the flint knife of the priest, who sacrifices his daughter to atone for her delinquency. I knew that Field had suffered thus, thousands of years ago, for even the writing of it occasioned him untold agony. He loved his heroine and wept over her; he wrote the last three chapters in a condition of ecstasy.

"Field was engaged to Miss Cynthia Latham, a charming girl from his native town of Salem. Now, to say that a writer's heroines may become rivals of his own fiancee or wife sounds like an absurdity. Yet, as Field wrote, the conviction dawned on him that his marriage would prove to be an unhappy one. Lota, the woman of his imagination, came to fill his heart, until she was more real than any woman of flesh and blood. Miss Latham was not slow to notice the change in him. She questioned him, but Field laughed and ascribed his erratic behavior to overwork. And Miss Latham let her faith overrule her judgment.

"It was two days before his marriage that Field came to see me. His eyes were bloodshot, his manner indicated that he was upon the verge of a nervous breakdown.

" 'Doctor,' he burst out excitedly, 'it is all over. I cannot marry her. I do not love her. I seem to be possessed by a perverse devil, for I love this woman of my creation more than anyone on earth. And I feel that in marrying Miss Latham I am committing an unspeakable sacrilege.'

" 'Do you remember that passage I read to you from my book?' he continued. 'Though we be severed through a thousand lives to come, each from each, yet I will find thee at the end? And then the lovers, embracing, and utterly convinced that some day they will be reunited, yield themselves to the knife without a pang? Doctor, I am that man. Laugh at my idea as you choose, I know it; and I know that somewhere in the world Lota, the heroine of my romance, is waiting for me to claim her. And if I fail her now I shall lose her forever.'

" 'The thing for you to do,' I answered, 'is to forget about your own hypersensitive emotional personality and think about Miss Latham. How would it affect her if the marriage were not to occur?'

" 'I know that it would break her heart,' he answered immediately. 'And yet, what is her love to Lota's? Has she waited for me ten thousand years?'

" 'Since the beginning of the world, Field,' I answered. 'Nothing is left to chance, though we make our own factors in the predestined totality. There is one thing that I have learned of life above all others; do the duty that lies before you and let your dreams alone, for these will work themselves out without your volition. If you are pledged to Lota, you have waited for her through a reasonably large number of incarnations, and you can reasonably wait until the next, when you will perhaps have acquired greater wisdom. Take my advice, Field; don't throw your chance of happiness away for a phantasy, but marry Miss Latham and spend your honeymoon in some romantic place where you will learn to send Lota packing back to the land of dreams.'

"He did not relish my remarks. Then I suggested that he let me hypnotize him. I thought that I might perhaps effect, by suggestion, some sharper cleavage between the normal man and the dreamer. With his permission I placed him under hypnosis and discovered, as I had anticipated, that the hypnotic state was the real one. Field hypnotized was Field, and not Field plus the Atlantean hero. So I sent the Atlantean back to his own lodgings and, when he awoke, Field was quite himself again and laughing at his imagination of ten minutes before.

"They were married as they had planned and were supremely happy. But a couple of months after their return from their honeymoon Field came to me in great perplexity.

" 'Doctor,' he said, 'I don't know what is the matter with me, but I can't write a word. I can't even get an original idea. And I've got to earn money. Diagnose my case; Isn't it the result of your treatment?'

"As a matter of fact, it was. In sinking down the shadowy, prehistoric Field, as I may as well call him, so deeply that he could not come into my patient's consciousness, I had also sunk down the imaginative faculty. Here was a nice problem before me; to restore just enough of the Atlantean to give Field back his imagination, but not enough to restore him to any semblance of personality. I was very loath to attempt to make this fine discrimination.

"'Go out and earn a living as a shoeblack,' I told him. 'Break stones for a living or be a clerk in a department store, but I won't call back that monster within you.'

"Field insisted. His demeanor became almost threatening. I had destroyed his earning capabilities, he told me; if I did not choose to restore them I could settle a handsome income on him in compensation. I had no right to ruin his life. Of course I yielded. But, in agreeing to hypnotize him, I told him that under no circumstances would I undo again—if, indeed, it could be undone. He assented and, placing him in a hypnotic sleep, I recalled the sleeping giant to the supraliminal world. Afterward Field went away, and he wrote to me a week later saying that he was hard at work on a new novel.

"All this had occurred when I was last in America. I was called back to Athens and did not return for nearly a year. When I did so, one of my first visitors was Cynthia Field. I confess that the sight of her distressed me greatly. I felt sure that some trouble had occurred. Had Field broken down, gone insane, left her? I was surprised and relieved when I discovered that she wished to consult me about herself.

"She had come to realize, she told me, that in marrying Field she had undertaken a responsibility for which she ought to have fitted herself. Her husband was a genius; he was largely dominated by his imagination. To fit herself for this responsibility she had read his unpublished work, and the horror of the denouement had come home to her so strongly that it had unstrung her. She had begun to dream of the book, and in her dreams she was Lota, the Atlantean woman, kneeling with Field before the sacrificial altar, and always she awoke just as the priest plunged the knife into her breast."

"Why is it that we always wake, in such cases, just as we are killed or murdered?" asked Tarrant.

"Because, my dear Tarrant, such dreams always represent a memory," answered Immanuel, looking at him fixedly. "There is not one of us who, in ruder periods of history, has not in some life or other endured a violent death. And our memory goes out with our lives; that is why we awaken."

Tarrant said nothing and Immanuel, after a turn or two about the room, proceeded.

"Well, to present the case concisely, the condition was this: Cynthia Field passed in her dreams into the personality of Lota, the priestess. And though in waking life she was devoted to her husband, in her sleep the image of Field presented itself to her as a jarring obstruction to her happiness. He alone stood between her and her happiness. And even after she awoke this sentiment persisted for an hour or two. Gradually her dreams were coming to color her waking life, to dominate it; she was growing to hate her husband; she accused herself bitterly and asked me what she could do to conquer this unnatural aversion. She took all the blame upon herself. I gave her some harmless prescription to make her sleep soundly and wrote an urgent letter to Field, asking him to call on me.

"I shall never forget the haggard look upon his face. 'I wish I had taken your advice and broken stones,' he cried. The old obsession had returned, but immeasurably more strongly. He knew nothing of his wife's psychical troubles and thought that he alone was responsible for the coldness that was growing up between them.

" 'It is only when I dream, doctor,' he said, 'that I become my normal self again. If it were not for that I think I should go mad. But in my sleep I see Cynthia again as she was when first I fell in love with her. In my sleep I love her more devotedly than ever, and it is this which sustains me against the day, when I hate her. What good will it do to mince words? I hate her by day, and think only of Lota, my beloved.'

"Here was a strange and complex situation. These two people's lives were at cross-purposes. The husband loved his wife asleep and hated her awake; she loved him when she was awake and hated him when she slept. But, as Freud has shown, our dreams are an intimate portion of our personalities and represent the fulfilment of our daily lives; they color our lives just as they take their form from them. Unless I could bring the two into harmony their future would be wrecked.

"I had long formed the idea that Mrs. Field was actually Lota, just as Field was the Atlantean. But so many lives had rolled between them since that last passionate pledge was made, to come, like all wishes, to its ultimate fruition—you know the text: 'Ask and ye shall receive'—I say, so many lives had elapsed that the soul of each had taken its own course of development. Field was no more the shadowy hero of his book than the sweet-natured New England girl was the Priestess Lota. And this is the situation which I outlined to you this evening at the beginning of our conversation. It was because its citizens had learned too many of nature's secrets that Atlantis disappeared, tradition tells us. If these two lovers had known nothing of the truths of reincarnation, far back in the days when Atlantis stretched, a mighty continent, where now the ocean rolls, they would never have made that vow which, by its very nature, pledged itself to its own fulfilment. Their souls would have passed into the limbo of things, ready to accept whatever was in store for them in other births, and therefore best. But they had flung their self-will into the teeth of eternity and had thus come together, not with the freedom of their new lives, but pledged to fulfil a vow which no longer corresponded to their needs.

"There were obviously two courses before me; either to recreate the Atlantean and the priestess, as well as it could be done, or to plunge both back into the fathomless depths of eternity, where they should both have been. The former course would, in this modern world, have been suicidal. I resolved to attempt the latter. But it is one thing to restore the psychic body of a forgotten life and quite another to destroy it. These phantoms have a personality of their own; they will not die; they cling to life as passionately as you or I. Yet in one respect they differ from us, because they can only live over again the episodes of their past; they are incapable of assimilating the experiences of this new life which they usurp.

"I was still thinking out my problem when I received another visit from Field. If he had appeared haggard before, this time he looked like a madman. He was unkempt, unshaven, and gave me the appearance of a man who had been on a prolonged debauch.

" 'You've got to do something at once, doctor,' he said, sinking down into a chair despondently. 'Cynthia tried to kill me last night.'

"I was horrified and yet not entirely astonished. I knew that, under the spell of her past, her normal life appeared strange and unreal to her. I quieted him and asked him for the particulars.

" 'It was about two o'clock.' Field answered. 'Of a sudden I awoke with a start out of a profound and happy sleep. I had been so happy, doctor! I was back again at Salem with Cynthia in the days of our courtship, before ever I was impelled to write that ghastly book. I awoke with a start and sat up. Cynthia was standing at my side, bending over me, one arm flung back. I seized it and forced her hand open. This is what I found inside.'

"He pulled from his pocket a sharp stone, with a razor-like edge, evidently taken from the road. It was just such a stone as is used by the thousand in macadamized streets; a flint, keener and harder than a razor blade. It was a fearful weapon; it would have mutilated him abominably.

" 'She seemed to have been dreaming. She stared at me as though she did not understand, and, I believe, since I concealed this stone, that she has had no remembrance of her attempt. But her nerves are all broken down and she has been lying in a sort of stupor all the morning.'

"This incident decided me. As you knew, gentlemen, I am the part owner of a sanitarium at Rutgers where I receive patients suffering from just such obscure nervous disorders as Mrs. Field's. I accompanied Field back to his home and persuaded his wife, whom I found in a very nervous condition, to be my patient there for a few days. I took her down the next morning and installed her in a comfortable suite of rooms under the care of a private nurse. Then I went back and ordered Field to meet me at the station a couple of days later. He did so and I took him to the sanitarium also, but did not let his wife know of his arrival.

"The brief rest and the change of scene, above all the separation from her husband, had immensely improved the woman's condition. I paid her a visit in her apartment after dinner and then asked her whether she would submit to being hypnotized. She was reluctant and afraid; in fact," said the doctor, smiling whimsically. "I must confess that I was only able to accomplish my object gradually; by pretending that it was what you in America call the 'Immanuel Movement' From Wikipedia: "The Emmanuel Movement was a psychologically-based approach to religious healing introduced in 1906 as an outreach of the Emmanuel Church in Boston.... In practice, the religious element was de-emphasized and the primary modalities were individual and group therapy. ... The primary long-term influence of the movement...was on the treatment of alcoholism [Alcoholics Anonymous]."—not named after myself, I think. In other words, I gained her confidence by a quiet conversation, darkened the room, focused her attention, and then brought out my glass ball and got her to stare at it under the belief that she was crystal-gazing—another form of hypnotism, of course. In the end she fell asleep. Then I left her and brought in Field. He knew my plans, and, skeptical as he was, he was willing that I should try rather than risk the probability that his wife would become incurably insane.

"I set him in a chair. 'Do you think,' I asked him, 'that you have enough confidence in me to sit there, perfectly still, no matter what happens? It depends largely upon your ability to do this whether or not I can effect a cure.'

"He promised faithfully, and I turned to his wife. She was seated in her chair, unconscious, exactly as I had ordered her to. 'Lota!' I said softly.

"Her lips moved and she murmured something. It was evident that this abnormal personality was in command, as I had expected it to be.

" 'Lota,' I said to her, 'what is the dearest wish of your heart? Is it not to be rid of that monster who keeps you from your lover?'

" 'Yes,' she answered, nodding her head and gazing at me blankly. 'Yes.'

" 'Would you kill him, Lota,' I continued, 'if you knew that in doing so you would die also? For your souls are so subtly bound together that, in the act of striking the blow, you yourself would die. You would kill your body to win your soul's freedom.'"

"My dear Immanuel," interrupted Tarrant, "that sounds to me like jargon. Is that sound doctrine?"

"No, of course not," answered the doctor briskly. "It is pure rubbish. But under hypnotism one believes whatever the operator says. And it was my purpose to get Mrs. Field to kill her husband, in imagination, and, in so doing, to kill herself—also in imagination. As I said, the phantom personality that possessed her could only live over again the episodes of the past. Mrs. Field had already tried to end her husband's life in the same manner as the priest had destroyed it, ten thousand years before—with a flint knife. Now, if I could get her to believe that the same climax had occurred again, both Lota and the Atlantean would be blotted out at a blow—and Cynthia would come to the surface forever. Do you understand?"

Tarrant nodded, half skeptically, and Immanuel continued:

" 'Yes,' she answered, I would kill him if I could, even if I died too.'

" 'Then take this flint knife,' I said.'Go to where he sits in that chair, and stab him through the heart.'

"And this was the crucial moment, for there is one exception to the rule that the hypnotized person obeys every suggestion of the operator. He will never commit a crime. That has been shown over and over again! Conscience persists, and, gentlemen, if ever there were needed proof of the existence of a moral order, you have it there. Would she stab him? If so, then she was verily Lota and not Cynthia Field.

"I placed the weapon in her hand and she arose, poised herself, and suddenly springing forward, caught Field around the neck with one arm, raised the other hand, and struck him to the heart with all her power. He fell from the chair. An instant later she had sunk down upon the floor, unconscious.

"Well, that was the end of Lota, gentlemen. She fulfilled her purpose and disappeared. It was Cynthia Field who awakened, never to disappear again. As for Field, he often begged me to try to complete his own personality, but I had already had experience of that and I declined to do so. I made him fight his battle alone. It was a hard struggle; but under hie wife's loving ministration he gradually won his victory, and if ever the shadowy Atlantean stirs in his heart, one look into his wife's eyes dissipates all his fears."

"But I thought she killed him!" exclaimed Paul Tarrant.

"O, that episode!" laughed the doctor. "I forgot to explain that. It wasn't really a knife, you know; it was a very mushy banana that I had taken from the dinner table. But she thought it was a flint knife—and so it answered its purpose."

Part of the series Phileas Immanuel, Tracer of Egos

Story illustrations from The Evening Republican, March 27, 1917. Source: Hoosier State Chronicles.